Sewage-sampling robots could help eliminate diseases in cities, says MIT architect Carlo Ratti

Robots could soon be infiltrating urban sewage systems to identify potential outbreaks of disease before they happen, according to architect and MIT professor Carlo Ratti (+ interview).

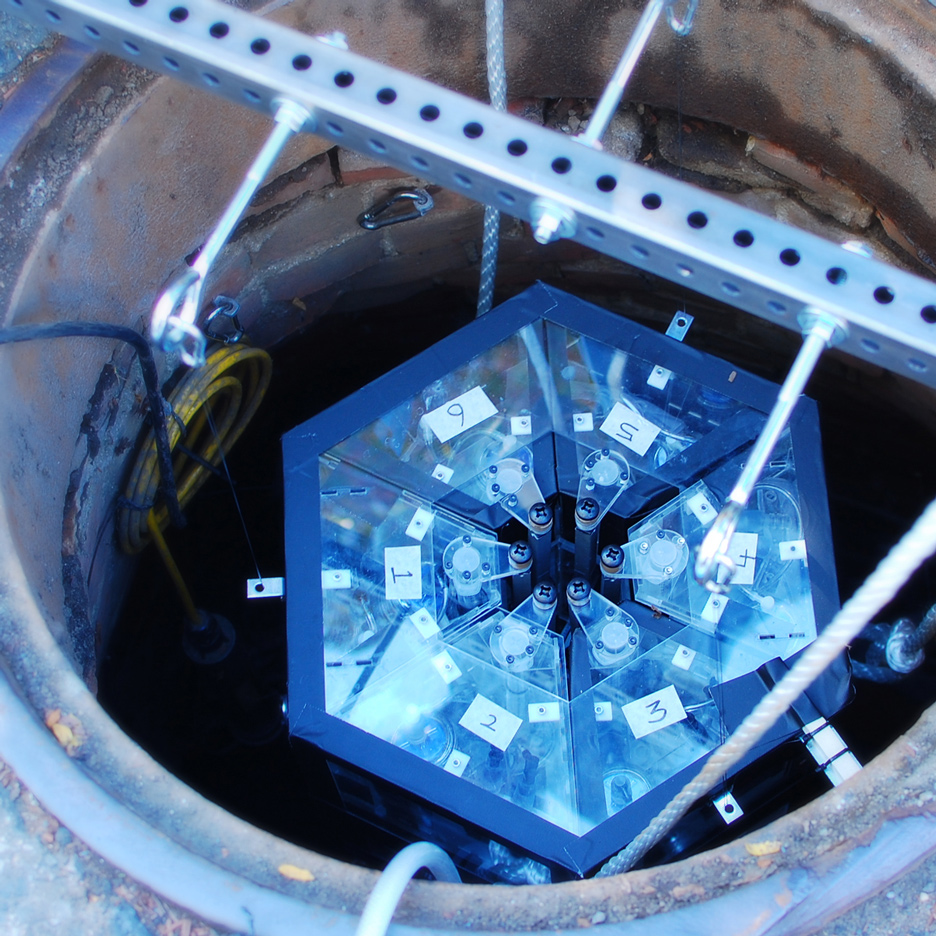

Ratti's team from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has created a prototype robot called Luigi, which is able to collect samples from city sewers, as part of a project called Underworlds.

According to Ratti, these samples could be used create a map of human health from biological data that would help scientists predict outbreaks of disease and possibly prevent them.

"We could be looking at epidemics before they happen," said Ratti. "So we're able to see the influenza virus before people have influenza."

The ongoing Underworlds project, which includes a team of MIT biologists and researchers, aims to prove that cities can make use of their waste water systems.

"We're collecting this information and we're using it to understand the micro-biome of the city," Ratti told Dezeen. "The applications of this are diverse."

The tube-shaped Luigi robot contains filters and can be guided via an iPhone app to collect samples from key points in a city's waste system, and is currently being used for pilot studies in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Boston. The filters collect the samples and can be removed for analysis and replaced to collect new data, and the robot is cleaned after each use.

Ratti said the data the team was collecting with Luigi could also show patterns of drug consumption in cities and help detect problems like antibiotic resistance.

The Italian architect spoke to Dezeen at New York's Cooper Union ahead of a talk earlier this spring about his work with the Internet of Things (IOT) – a collective name for everyday devices, objects and systems that are networked via Wi-Fi to share and respond to data.

His other projects include traffic infrastructure for driverless cars, smart modular seats that can be reconfigured with hand gestures, and offices where heating, lighting and cooling systems follow occupants around the building.

"Our cities are becoming these kind of cyber-physical systems," Ratti said. "Cyber-physical includes both the physical and the biological, and that means that we have a great wealth of information to understand them and to transform them."

"That is radically changing architecture, cities, planning and so on, because it's the natural entry space in creating this hybrid system," he added.

Ratti, 45, is the director of MIT's Senseable City Lab, which investigates and anticipates how digital technologies are changing the way people live at an urban scale.

He also runs his own Turin-based firm, Carlo Ratti Associati, where the same technologies are explored through architecture, planning and design.

"What we see is a beautiful frontier of architecture and planning, which brings together the physical, the digital and the biological," said Ratti.

Read an edited transcript from our interview with Carlo Ratti:

Dan Howarth: Can you briefly explain your different roles?

Carlo Ratti: I have three hats, one is the professor at MIT's Senseable City Lab, one with the design office Carlo Ratti Associati and then in the past couple of years, a few startups with Copenhagen Wheel, Makr Shakr and a few others.

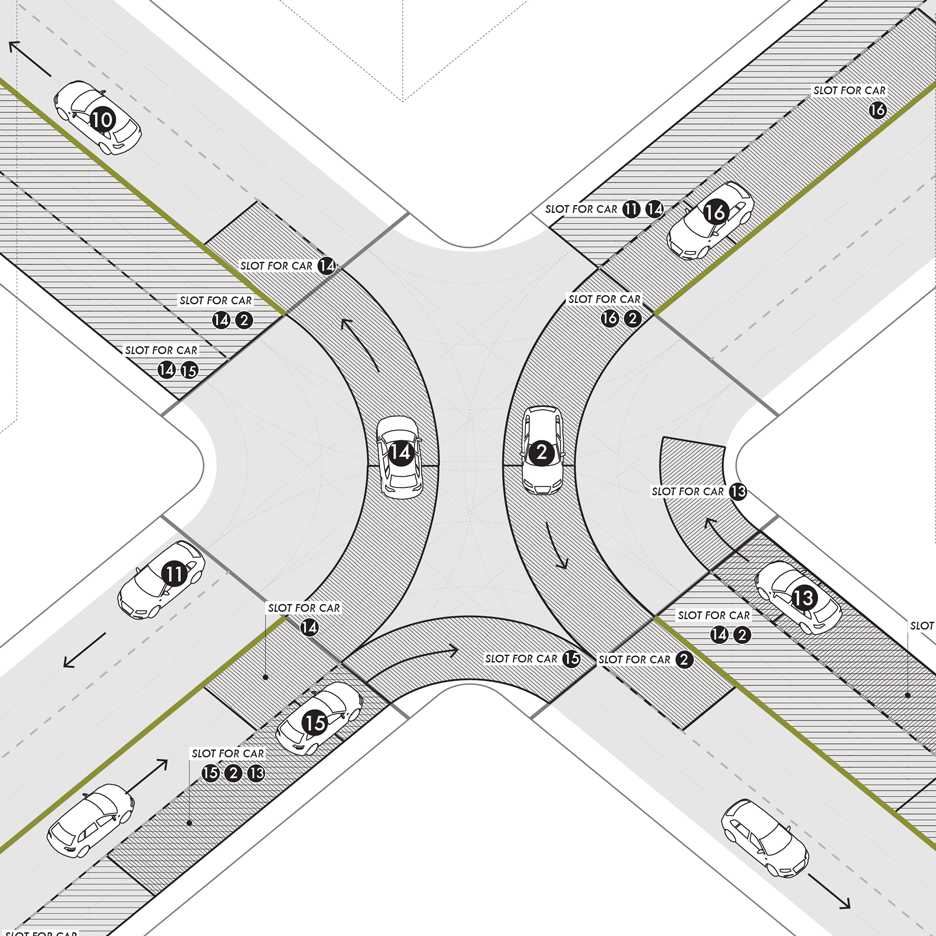

Dan Howarth: Tell me about what you're doing with driverless cars.

Carlo Ratti: Driverless cars are coming to the street, they are reality as we speak. There are probably hundreds of them being tested around the world. The exciting thing is that driverless cars will blur the distinction between private transportation and public transportation. That means the car can give you a lift in the morning when you go to the office and then it can give a lift to somebody else, and then somebody else in the city.

We are doing some theoretical work showing that in places such as New York you could potentially run the whole city with 20 per cent of the cars we have today, and still take everybody to where they need to be when. It would be an amazing change in the way the city operates.

Dan Howarth: So the idea is that cars are continuously cycling around the city, and people just hop in and out of them?

Carlo Ratti: To a certain extent, you will still have times when you need more cars and less cars but still you have this mobile infrastructure that works much better. The car is one of the most inefficient pieces of urban infrastructure, we use a car five per cent of the time. The other 95 per cent the car is parked somewhere without anybody in it and is using valuable parking space.

Dan Howarth: What do you think about Bentley's idea that rich passengers could pay more for faster driverless car lanes?

Carlo Ratti: Technology can allow us to do that, it is not a scandal to talk about that. If you think about how I'm flying tonight to Miami with a standard regular airline, I could fly there with a private jet and I could probably get there faster at any time I want.

Today it already happens that if you pay more you get better transportation. If we want to go there however it's a decision we need to discuss together. It's a political decision not a technological decision. It's important for designers to see what the potential is but then society needs to make a choice. Is this what we want? For people inside the city, the system of "if you pay more then you get there faster and you avoid traffic lights and if you pay less you're stuck in traffic"? I think that is something we should all discuss.

Dan Howarth: What other kinds of research are you doing at MIT?

Carlo Ratti: One of the projects that actually intersects most of things that we are doing now is a project where we had robots going in to sewers and sample sewage, and then we looked at all the viruses and bacteria in the sewage. In our guts we have more viruses and bacteria than cells in our body. For every cell in our body we have about nine or 10 viruses and bacteria living with us. This is a big component of our health and who we are.

It's very difficult to monitor it on an individual level but there's a beautiful aggregate in cities, which is sewage. So we're collecting this information and we're using it to understand the micro-biome of the city. The applications of this are diverse; we could be looking at epidemics before they happen, so we're able to see the influenza virus before people have influenza. We are seeing drug consumption as well. We are able to also look at all these colonies of viruses and bacteria, and how we could look at new therapies that go beyond antibiotics.

We are doing that project together with people from biological engineering at MIT and in other departments. What we see is a beautiful frontier of architecture and planning, which brings together the physical, the digital and the biological.

Dan Howarth: Why is this a good task for robots?

Carlo Ratti: Originally we went in to sample the sewage, but we discovered that it was not that fun. So we built a robot that's called Luigi that goes down and samples.

Dan Howarth: How does the robot collect the samples, and how does it know where to go and where to take them from?

Carlo Ratti: First we do a lot of modelling of the sewer system to see how the sewage is representative of different parts of the city. Then we go and put the robot in different parts of the city so that it can collect something that is representative of a certain neighbourhood instead of an aggregate.

Dan Howarth: What does the combination of these projects mean for the future of cities?

Carlo Ratti: What we believe is happening today is that our cities are becoming these kind of cyber-physical systems. Cyber-physical includes both the physical and the biological. And that means that we have a great wealth of information to understand them and to transform them.

Dan Howarth: How exactly would you define a cyber-physical city and how are we going to live in them?

Carlo Ratti: It's about a city where the digital system and the physical system work together.

The internet until now was something separate, now it is becoming the IOT, so it's entering physical space. That is radically changing architecture, cities, planning and so on, because it's the natural entry space in creating this hybrid system; this cyber-physical system. The mechanism behind it is cybernetics, that allows this communication between the network and the city and so on.

Dan Howarth: How do you think this is going to develop? How will these cities evolve in the next few years?

Carlo Ratti: I think what we're going to see more and more is an architecture that comes alive. It's always been said that architecture is the third skin; we have our own skin and then the skin of the clothes and then we have architecture. But as a skin, it has always been very rigid, uncompromising, almost like a corset.

I think tomorrow we can think about an environment that can become much more responsive because of these cyber-physical loops. For instance what we presented at design week in Milan is a totally mouldable thing. Again it's an architecture that moves with us.

The idea was for a system that is based on elements, each element has a linear equator so it goes up and down. You can control it with your phone or you can put your hand on it, and if you put your hand on it, it goes up or goes down. You can control it just by hovering it over the place and it has a sensor that tells you the capacity and changes the capacity and then it goes up and down and they create a reconfigurable environment.

Dan Howarth: So this has implications for furniture as well as architecture?

Carlo Ratti: Anything from furniture to buildings to cityscapes.