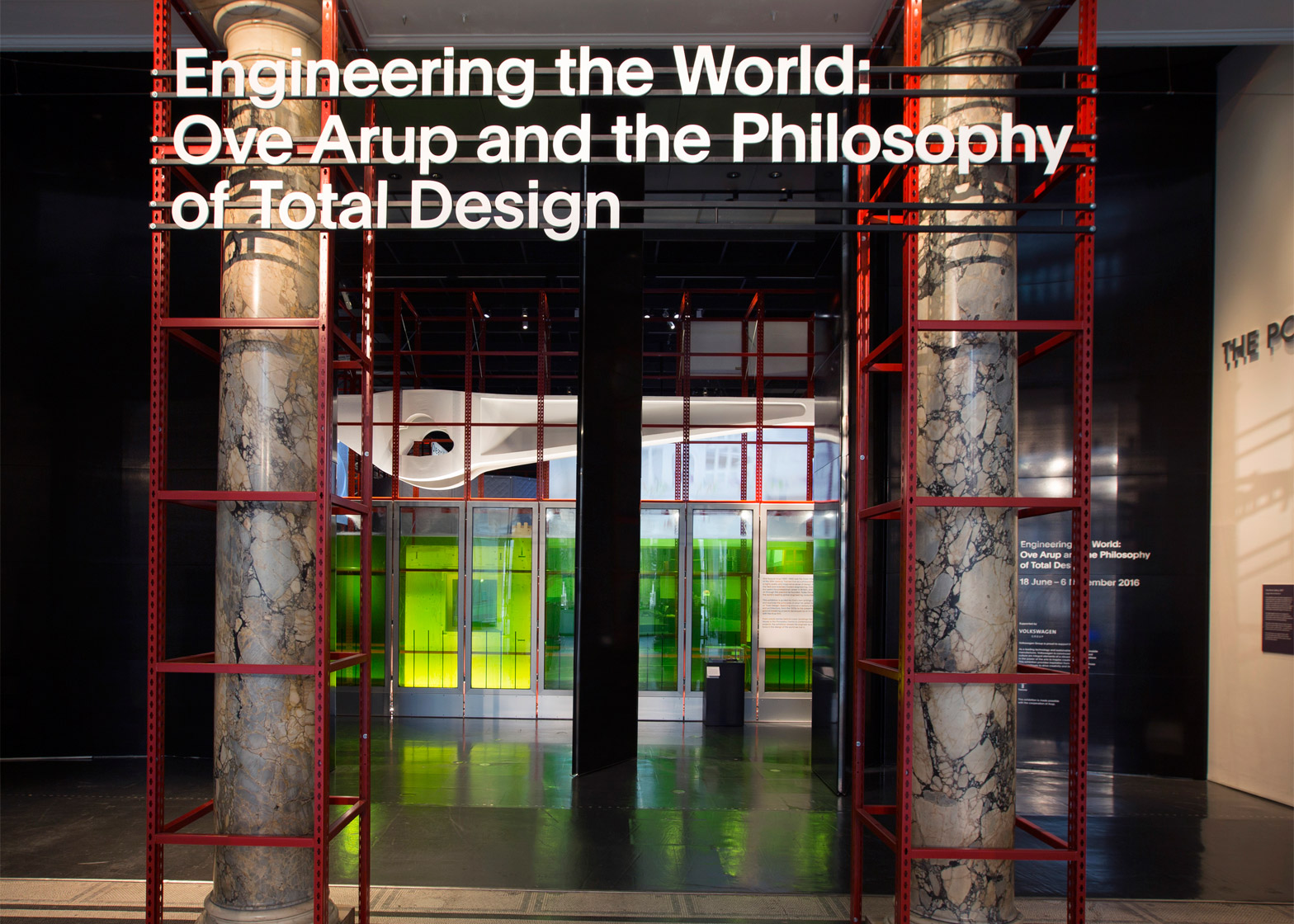

An exhibition has opened at London's V&A museum charting the career and legacy of Ove Arup, who "forged a new role for engineers" in the 20th century (+ slideshow).

As the headline exhibition in the V&A's engineering season, Engineering the World: Ove Arup and the Philosophy of Total Design opened to the public last week. It is the first engineering retrospective the museum has ever staged.

It examines the work of the late engineer, who made the best-known designs of architects including Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers and Norman Foster a reality.

His extensive portfolio includes the Sydney Opera House, the Centre Pompidou, the Kingsgate Bridge, the London Zoo Penguin Pool and the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank HQ.

"Leading architects such as Richard Rogers and Norman Foster owe their exciting careers to Ove and his firm, who pushed the boundaries and stimulated new ideas," explained exhibition curator Zofia Trafas White.

"Ove forged a new role for engineers," she told Dezeen. "We want people to see these iconic buildings with fresh eyes, and show people that they do know Ove. He's been here the whole time."

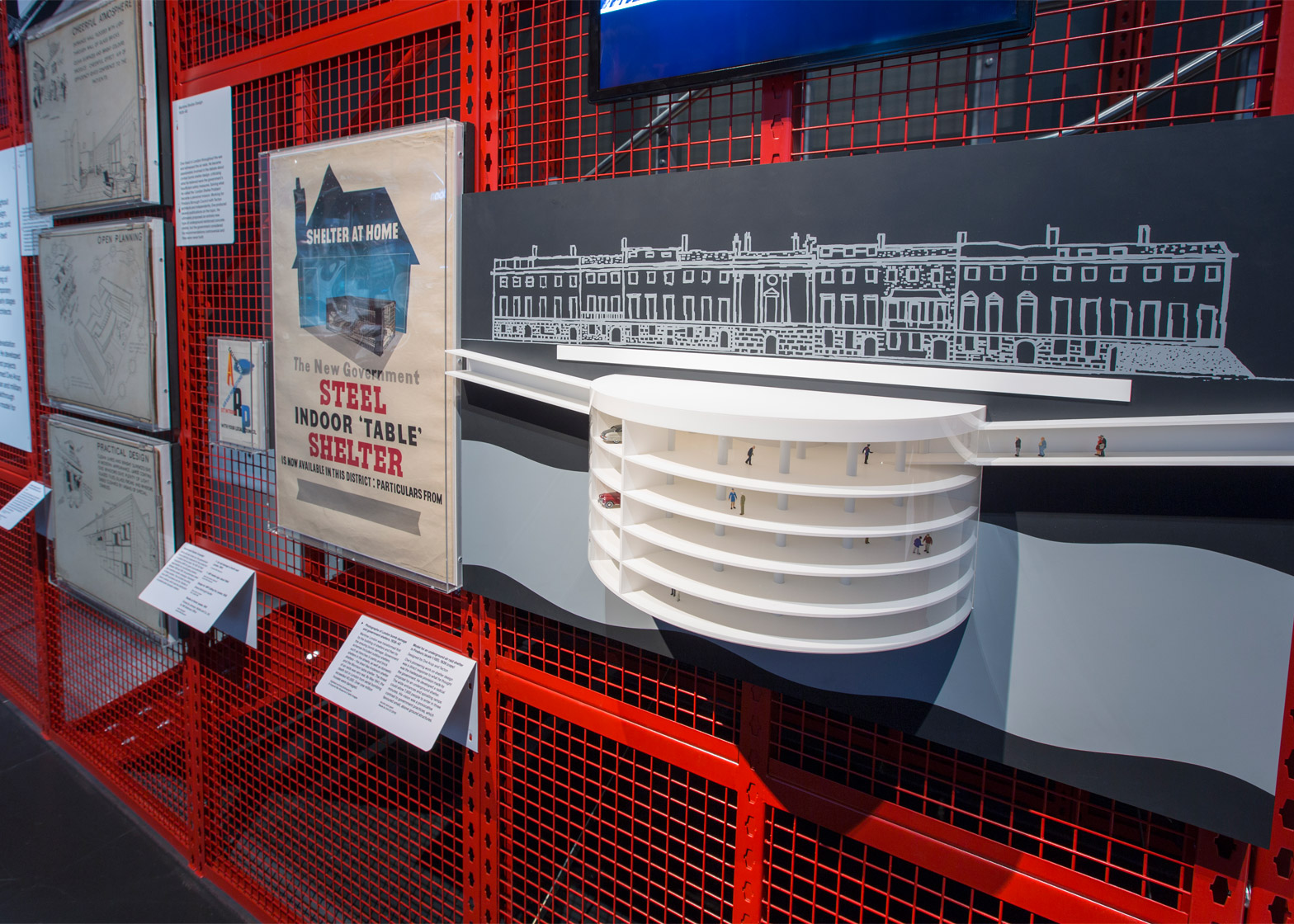

The exhibition is split into three parts – A Portrait of Ove Arup, Ove and His Firm, and Arup after Ove. It includes over 150 previously unseen prototypes, models, drawings, photography and films spanning over a century.

The first section focuses on Arup's early relationship with Modernist thinkers, namely Bauhaus school founder Walter Gropius.

Gropius encouraged Arup to collaborate with architects in a personal letter in 1966. His advice helped shape the engineer's pioneering philosophy of Total Design, which urged engineers and architect to work together on projects from start to finish.

Arup's breakthrough projects are on display in the second section, including the Jørn Utzon-designed Sydney Opera House, which was the first structure to be built using computer-generated calculations.

"Ove showed what it really means to integrate technology to solve a design problem," explained White.

"He has shaped concrete Super-Modernism, the first unbuildable curves, the first iconic buildings. The Sydney Opera House remains one of a kind."

This section also includes Arup's pioneering work in the 1970s, which included teaming up with Piano and Rogers on the Centre Pompidou in Paris, which opened in 1977.

His role encompassed putting the building's services on its exterior, including the staircases and lifts. These exposed elements became the building's defining feature, and laid the groundwork for many of Rogers' later buildings, particularly the Lloyds Building in London.

"You can no longer separate the engineer from the architect," said Zofia. "Look at the Cheesegrater in London, look at Foster's HSBC bank. The thinking of how to construct a building actually defines its aesthetic."

The final section of the exhibition looks at the achievements of Arup's firm – known simply as Arup – since his death in 1988. Project range from the UK's high-speed rail network, Crossrail, to an innovative facade system that generates renewable energy from algae.

"What this ultimately shows is that some of the most iconic recognisable buildings would never have been built without Arup engineers," said White.

"Throughout the 20th century, Ove's firm and its followers forged a different way of looking and a different role for the engineers," she continued. "Engineers are there from the start, they're no longer coming on to solve the problem."

Arup now has offices in 38 counties and is involved in many of the world's most important architectural projects. Recent examples include Zaha Hadid's "oyster-like" ferry terminal in Italy and OMA's Shenzhen Stock Exchange.

The firm has also been involved in numerous experimental projects, including 3D-printed structural components and a glass "sky pool".

Engineering the World: Ove Arup and the Philosophy of Total Design runs until 6 November 2016. Also part of the V&A's engineering season, a team from the University of Stuttgart has used robots to build a woven carbon-fibre pavilion in the museum's courtyard.