"Design has gone viral, but design community is stranded" say Istanbul Design Biennial curators

Today's radical ideas rarely come from designers according to Istanbul Design Biennial curators Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, who say the entire industry is 200 years out of date (+ interview).

Colomina and Wigley – who teach architecture at Princeton and Columbia respectively – claim that design has become a cultural phenomenon, with huge public interest generated by online and social media. But designers have been left behind.

"Design has gone viral in a big way. But the design community is stranded in an older idea about design and an older behaviour," said Wigley during an exclusive interview with Dezeen.

The proof of this, he said, is the way that most design exhibitions and biennials are put together.

"They have become like trade shows," he said. "Biennials have become a way of telling the world that everything is okay and that design is going on, but you're not really invited to think."

In response, the husband-and-wife duo have planned their Istanbul Design Biennial next month as "an attack on good design".

They plan to showcase the work of scientists, historians, archaeologists and artists, to question whether design as an industry could be more ambitious.

"It is a call to rethink what design is in our time," said Colomina.

"Our economy and our ways of producing have changed so radically, so we need a new concept of design. And the only way to get to the bottom of this is by expanding the discussion beyond the industrial design of the last 200 years and going back to the roots of what design is."

Titled Are We Human? the show will question whether the practice of design is unique to humans.

Through various installations and film screenings, it will explore the extent to which design has transformed the planet, shaped the evolution of the human body and even mapped out a path to extinction.

Colomina described the results as "enough to blow your mind".

"We want people to come away from our show feeling the need to invent new concepts of design," added Wigley. "We need to gather the troops, because we're in an extreme, shocking and scary world where the old concept of good design is no longer very good."

"It's emergency button time, and it's exciting."

Dezeen is media partner for the third edition of the Istanbul Design Biennial, which is organised by the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts. The show runs from 22 October to 20 November 2016.

Dezeen readers can win tickets to the event by entering our competition before 4 October 2016.

Read on for an edited version of the interview with Colomina and Wigley:

Amy Frearson: What were your first thoughts when you were asked to do this biennial?

Beatriz Colomina: The first question became, what actually is design? It became about investigating that idea, the very idea of design, which goes back about 200 years. But we were critical of the biennial. We immediately thought: "What is a biennial supposed to do? Cover the last two years of innovation in design?" But with the proliferation of biennials all over the world, what would this mean? It's not very interesting.

So we thought about expanding the bandwidth of design over a period of 200,000 years, from the beginning of humanity to the world of social media. And we thought of it in powers of two. Two years of the biennial, 200 years of industrial design as we know it today, 200,000 years of humanity, and the two seconds of social media, which is one of the places where we are designing more today.

Mark Wigley: Biennials can be fantastic because they create this urban congestion of people from around the world, a kind of temporary city that descends on the existing city. But when you look at biennials, it's not really what's going on. They have become like trade shows. You see work that's sort of new, but it's the same people doing it. So biennials have become a way of telling the world that everything is okay and that design is going on, but you're not really invited to think.

So why did we said yes to doing one? We thought that it could be really exciting, because right now design might be the most urgent question. And maybe we can get people together in Istanbul to talk about that. And we were unclear about whether you can have a great conversation about design in London, Paris, Milan, New York, or any other place where everyone thinks they know what design is. Istanbul seemed like a fresh place to do it.

Amy Frearson: Tell me about the theme you've chosen: Are We Human?

Beatriz Colomina: The idea is that design is what makes us human. Man is the only animal that designs, so it is therefore through design that we can ask questions about humanity.

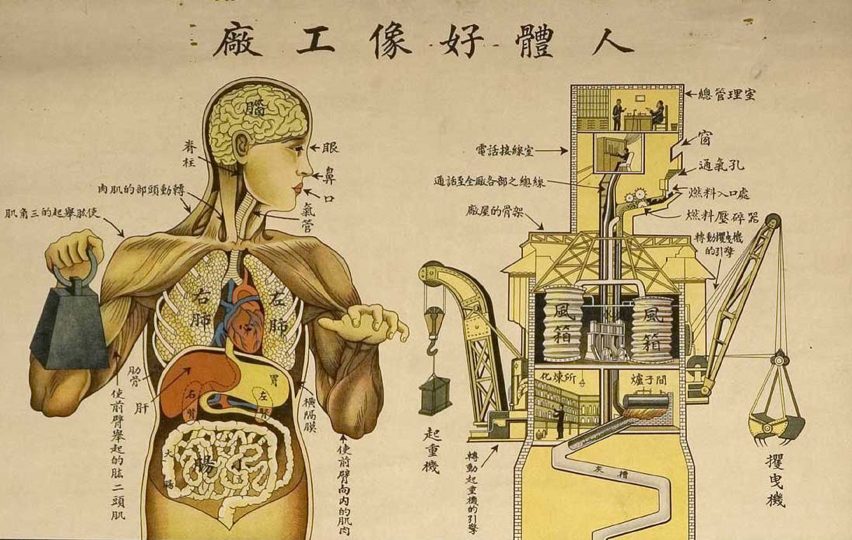

Mark Wigley: The question is, what if the real subject of design is, and has always been, the human? And what if design is actually more radical than we've ever thought? That we reshape our bodies and brains and aspirations and even the planet? What if the whole planet is now entirely covered with a geological layer of design? What if that goes deep into the ground and deep into outer space? What if the human being is permanently suspended in design? Then what would we think about design?

As you walk through the city, you walk through thousands of different layers of design. It's like clothing, like we are wearing thousands of layers of design. You don't really move through a city, you move through smells, signs, people, noises, all of which are design.

Beatriz Colomina: It is design that defines us, whether it's a shoe that ends up modifying the shape of the foot, or a cell phone that changes not only our hands but the way our brain functions.

Amy Frearson: So your message is really that design is not just the realm of designers, but everyone?

Mark Wigley: Design has gone viral in a big way, but the design community is stranded in an older idea about design and an older behaviour. So we want our biennial to make a series of links between the world of the designer and the world of design.

It could be a great moment to come up with some new concepts of design, especially because the old one is so successful. There's a great Marshall McLuhan quote: "If something works, then it's obsolete". So maybe we have a concept of design that is so explosively successful that we need to ask the design community for a new concept of design.

Instead of saying "here's my coffeepot", you could say "here's the human that I imagined". Design could be more ambitious.

And why the human? Why are we the only species that designs? That's the really big question.

Beatriz Colomina: And we have taken this to extreme by designing useless things, and catastrophic things as well. In that sense, we are the only animal that has managed to design its own extinction.

Mark Wigley: I guess it's more like archaeology. You have to think about the old story, where gibbons start making tools and shelters, and eventually they domesticate themselves in settlements, and the more settled they get the more they start to communicate and decorate, and they start to find that certain things no longer work. But what if it's the other way round? What if we communicated first? What if we designed first? What if I make something beautiful and I become attractive, so then I have a sexual partner, so I survive? What if ornament is how we survive? And what if the other things came second?

We're very interested in that. Like Beatrice was saying, the human makes tools that don't work. That's unique. We're the only species that does that.

Beatriz Colomina: When look at archaeology we discover that many of those tools we thought were functional have turned out to not be very functional at all. But they are full of layers of decoration, and they are another form of survival in that sense.

Amy Frearson: How are planning to demonstrate these ideas with your exhibition?

Mark Wigley: Firstly I should say there are many designers and architects involved, but also artists, archaeologists, brain scientists, historians, curators, filmmakers, a different mix than you would normally find at a design biennial. And people are sending in videos – anyone who sends in a two-minute video, as long as it's exactly two minutes, it's in the show.

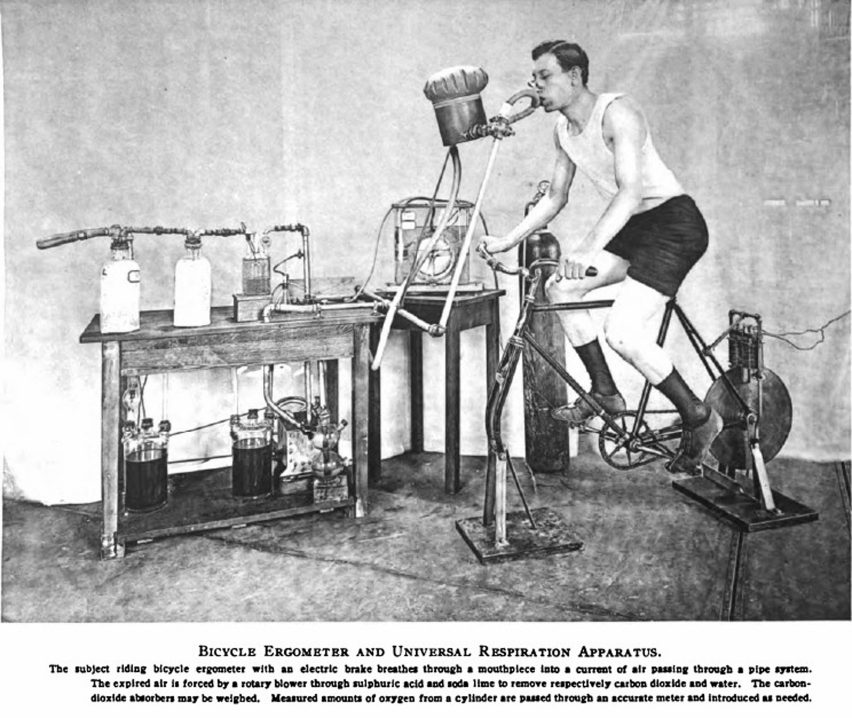

So in one section you will experience about 25 different projects dealing with the human body, all saying that the body is a primary site for design. There's nothing stable about our bodies – we have very radical relationships with them. The human is like a question mark, unstable in design. But we're not doing science fiction, the show is a documentary.

You can design your children. You can design new species. You can replace almost any part of your body. It's something that we all know but we don't think about how radical it is.

Beatriz Colomina: The brain is a huge part of this discussion too. There's a lot of new research on the way the brain works, on what makes it different from animals, and different from artificial intelligence.

Mark Wigley: Then there's another section about the design of the planet. We have a group of projects that look at places where you think there's no design: Antartica, the Mediterranean, under the ground, in outer space, on the top of trees, even dust. We're showing people that there really is design going on at the scale of the planet.

Then there's another section looking 200,000 years ago. We have a wonderful relationship with the Istanbul Archaeologic Museum, which is a bit like the British museum, that amazing. They are close partners because we said that their museum is a design museum, and they were so happy to hear this.

So here you can see neolithic tools that were dug up when they made a new subway in Istanbul. And you can even see the footprints. We want people to try to understand the relationship between their cell phones, these neolithic tools and these footprints. And to question which of our design objects today will end up in archaeological museums.

When you look at these ancient objects, you really see the beginnings of architecture and cities, and then you ask questions.

We really hate these shows where each each designer has their little space, their little cubicle, and they show their latest thing. We want it to be like when you walk into an old shop that's a bit dusty, but there are an amazing variety of things. And you see something in the corner and it's a bit hidden, and you ask if you can take a closer look. Your head is constantly spinning around, but you start seeing connections.

Beatriz Colomina: We want to show clouds of things rather than isolated objects. We don't have objects, we have projects and the projects are always asking different kinds of questions.

Mark Wigley: It's weird how, at a typical biennial, you walk through the streets of a city and experience all this noise and complexity, all this design. Then you go inside, where there is one object sitting on a little vitrine and you're supposed to treat it like a religious relic. But it's somehow less than the city that you're in.

We want you to still feel like you're in the city when you're in our show, where you get to make your own decisions. It's not going to be a show where you're told what your reactions will be. We don't have the answers.

Amy Frearson: What do you expect visitors to take away from the show? Are you expecting to provoke any real change?

Beatriz Colomina: I hope it will change people's idea of what design is. Rather than concerning only a very small fragment of society – designers and the community that supports them – design involves us all. We have managed to cover the planet with design and we have managed to carefully design our own extinction.

For us, the message is clear. Reality is much stranger than fiction. We don't need to anticipate the future, what we've already done is enough to blow your mind.

Mark Wigley: That's really the crux of it. We live on the edge of extreme design, and that's ordinary life. Then when you go to a normal show, you see non-extreme design, a kind of dumbing down.

We want people to come away from our show feeling the need to invent new concepts of design. We need to gather the troops, because we're in an extreme, shocking and scary world where the old concept of good design is no longer very good. So the show is definitely an attack on good design.

Beatriz Colomina: It is also a call to rethink what design is in our time. Our economy and our ways of producing have changed so radically, so we need a new concept of design. And the only way to get to the bottom of this is by expanding the discussion beyond the industrial design of the last 200 years and going back to the roots of what design is.

Mark Wigley: For instance, you can look at the refugee crisis that has dominated everybody's consciousness over the last few years, and you could try to design a solution to that. But wouldn't it better to try to understand how design is part of that situation, how we designed that situation? To do that, you need better concepts of design.

It's emergency button time, and it's exciting. Because if design is what makes us human, then that means humans by nature love to think how something could be done differently. Maybe design is not rocket science, it's just the curiosity that humans have.

Beatriz Colomina: In fact, one of the scientists we have in the exhibition was looking at the difference between a human brain and artificial intelligence, and the answer she came up with was curiosity. Curiosity is what make us do things differently. When animals come with something that works they stick to it, and they pass it on from generation to generation. But we constantly invent new ways and design things that are not useful at all.

Mark Wigley: The point we are making is, wouldn't the ability for design to ask questions be a more valuable contribution to contemporary society than our ability to answer questions? In truth, you don't really need a designer to make solutions, most of the big radical design going on in our world does not involves designers or architects. It is design, but it's being done differently.