Norway moves to scrap plans for controversial Utøya memorial

The Norwegian government has offered to abandon plans for a memorial to the 77 people murdered during the terrorist attacks of 22 July 2011, after fierce opposition by local residents.

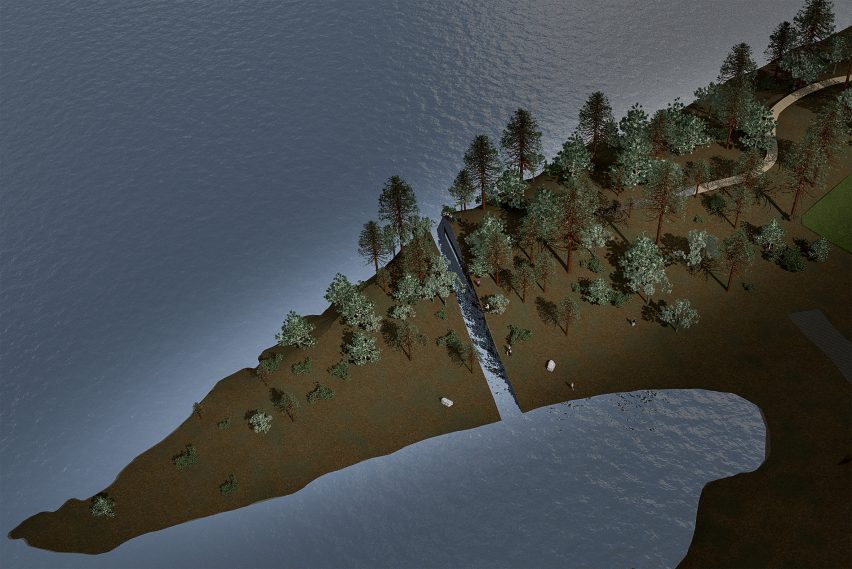

Swedish artist Jonas Dahlberg intends to sever a strip of headland from the coastline in the village of Sørbråten, in tribute to the victims of the bombing in Oslo and the shootings that followed on the island of Utøya.

But locals have campaigned for years to block the project, which they have described as a "rape of nature", a "tourist attraction", and a "hideous monument", according to news website The Local.

Under threat of legal action, the Norwegian government offered to cancel the project, known as Memory Wound, and relocate it elsewhere.

However residents have declined a settlement offer and are now pushing for the project to be completely scrapped.

Dahlberg first unveiled plans for the memorial in 2014. He intended to create "a wound or a cut within the landscape" to symbolise the feeling of loss created by the two politically motivated attacks, both carried out by far-right terrorist Anders Behring Breivik.

The 3.5-metre-wide slice would make it impossible to reach the end of the headland – just across the water from Utøya – on foot.

Dahlberg has now called for the government to worker harder to find a compromise to ensure the artwork is still created.

In a lengthy statement, he described the public negotiations as "an important part of the grieving process" that the government has a duty to carry out.

"Most comparable memorials in other parts of the world have undergone even longer periods of uncertainty before they were completed, compared to the five years that have passed since the events of 22 July in Norway," he said.

"Many have also been surrounded by similarly complex discussions. Overseeing this delicate situation, and gently guiding the conversation, is a responsibility of the government."

Dahlberg had planned to use the material excavated from the Sørbråten site to build a second memorial at the government quarter in Oslo, forging a connection between the two attack sites.

Cancelling – rather than relocating – the Sørbråten project would also make it impossible to create the second memorial.

The artist said it is "more important than ever" to draw attention to the motivations behind the "act of political terrorism", and is hopeful that the two memorials will be completed as planned.

"A memorial that proposes a state of consensus, a form of silence, would also diminish the events and make it easier for the circumstances to be forgotten in time," he said.

"I believe that the purpose of a national memorial site is to honour the lives lost by insisting on a continued and collective conversation about the events leading to it. The conversation itself, even if at times uncomfortable, is what can work as a way of processing the trauma in the long run."

Despite the continued opposition, the government had said as recently as May that the threat of lawsuits was not sufficient grounds to change the plans for the Sørbråten memorial.

The turnaround was announced last week by local government minister Jan Tore Sanner.

"We want to avoid a long and harrowing trial, and have proposed a settlement that includes us abandoning the selected artwork," said Sanner, reported The Local.

"We have asked the attorney general to investigate the feasibility of launching settlement negotiations that would entail keeping Sørbråten as the memorial location but would involve all concerned parties in the decision to find another memorial instead of Memory Wound."

Harald Stabell, the lawyer hired to contest the memorial, previously argued that its presence would damage the mental health of locals who participated in the mission to rescue survivors fleeing from Utøya on the day of the attacks.

Stabell claimed his clients were not opposed to having the memorial within Hole Municipality, but that they didn't want to be in Sørbråte. By declining the government's offer, they have undermined this claim.

Memory Wound is not the only memorial being created to honour the victims of the attacks. 3RW installed a giant silver ring on Utøya last year, while architect Erlend Blakstad Haffner has enshrined one of the buildings on the island within a new learning centre.

Read on for the full statement from Jonas Dahlberg:

On Monday 5 September I was notified that the Norwegian Government had decided to try to reach a settlement with the group of 22 local residents of Hole Municipality, headed by local Fremskrittspartiet politician Jørn Øverby, that has filed a lawsuit against the Norwegian State in order to stop the 22 July National Memorial Site at Sørbråten, close to Utøya.

The Government's proposition means cancelling the work at the Sørbråten site, one month before construction was scheduled to begin. The intention would be to restart the process and find a new design for the memorial, with the involvement of the local residents. On Wednesday September 14 I was informed that the local residents had declined the settlement offer.

I am convinced that the public debate about the memorials in Hole and in Oslo is an important part of the grieving process necessary for a community. Most comparable memorials in other parts of the world have undergone even longer periods of uncertainty before they were completed compared to the five years that have passed since the events of 22 July in Norway.

Many have also been surrounded by similarly complex discussions. Overseeing this delicate situation, and gently guiding the conversation, is a responsibility of the Government.

The events of 22 July 2011 were an act of political terrorism. It is more important than ever to talk about its causes and context in the current political climate. A memorial that proposes a state of consensus, a form of silence, would also diminish the events and make it easier for the circumstances to be forgotten in time.

I believe that the purpose of a national memorial site is to honour the lives lost by insisting on a continued and collective conversation about the events leading to it. The conversation itself, even if at times uncomfortable, is what can work as a way of processing the trauma in the long run.

I am grateful for the opportunity to work with the 22 July National Memorial Sites for the past three years, and for the faith entrusted in me by the victim's relatives and the survivors.

I hope that I will have continued trust to complete the work on the memorials in Hole and in Oslo. The work and the people I have met have changed my life forever.