Aga Khan Award for Architecture 2016 winners announced

Iran's largest pedestrian bridge, a pink rubberised park by BIG and Zaha Hadid's first building in Lebanon are among the six winners of this year's $1 million Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

The three other winners of the triennial architecture award are a labyrinthine community centre and a perforated brick mosque, both in Bangladesh, and a library in a Beijing hutong.

The architects of each project will receive a share of a $1 million (£700,000) fund, which makes the Aga Khan Award for Architecture one of the world's most lucrative architecture prizes

The six projects – located in Bangladesh, Denmark, China, Iran and Lebanon – were selected from a shortlist of 19 projects unveiled in May 2016.

They were chosen by a committee including architects Emre Arolat, David Adjaye and Dominique Perrault, and His Highness the Aga Khan.

The Aga Khan Award for Architecture was set up by His Highness the Aga Khan in 1977 to acknowledge and encourage projects that address the needs of Muslims the world over.

A ceremony will be held for the winners of the 2016 award at the Al Jahili Fort – a World Heritage Site in Al Ain that itself received the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2007 following a significant renovation.

Here's some more information about each winning project from the competition organisers:

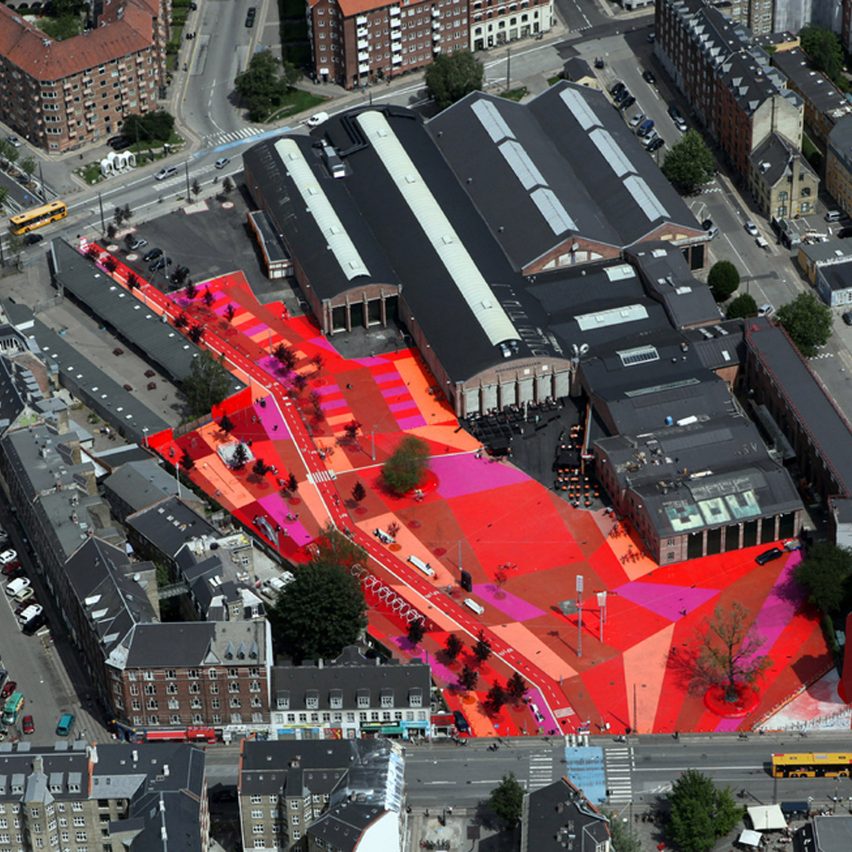

Superkilen, Copenhagen, Denmark, by BIG, Topotek 1 and Superflex

A meeting place for residents of Denmark's most ethnically diverse neighbourhood and an attraction for the rest of the city, this project was approached as a giant exhibition of global urban best practice.

In the spring of 2006 the street outside the architects' Copenhagen office erupted in vandalism and violence. Having just gone through the design of a Danish mosque in downtown Copenhagen, BIG with Topotek1 and Superflex chose to focus on those initiatives and activities in urban spaces that work as promoters for integration across ethnicity, religion, culture and languages.

Taking their point of departure as Superkilen's location in the heart of outer Nørrebro district, the architects decided they would approach the project as an exercise in extreme public participation. Rather than a public outreach process geared towards the lowest common denominator or a politically correct post rationalisation of preconceived ideas navigated around any potential public resistance, BIG, Topotek1 and Superflex proposed public participation as the driving force of the design.

An extensive public consultation process garnered suggestions for objects representing the over 60 nationalities present locally to be placed in the area.

The 750-metre-long scheme comprises three main zones: a red square for sports; a green park as a grassy children's playground; and a black market as a food market and picnic area.

Tabiat Pedestrian Bridge, Tehran, Iran by Diba Tensile Architecture, Leila Araghian and Alireza Behzadi

The two-to-three level, 270-metre-long curved pedestrian bridge of varying width has a complex steel structure featuring a dynamic three-dimensional truss. Two continuous deck levels sits on three tree-shaped columns, with a third where the truss meets the column branches.

It was an imaginative leap beyond the basic competition brief of designing a bridge to connect two parks separated by a highway in northern Tehran, without blocking the view to the Alborz Mountains.

The structural elements are based on a latent geometrical order rotated and repeated in three dimensions. The result is a spatial structure large enough to create an inhabitable architectural space, where people congregate, eat and rest rather than just pass through.

Multiple paths in each park were created that would lead people on to the bridge. Seating, green spaces and kiosks encourage people to linger on a site where greenery has been preserved by the minimal footprint of the bridge, whose curve offers a variety of viewing perspectives.

Bait Ur Rouf Mosque, Dhaka, Bangladesh by Marina Tabassum

After a difficult life and the loss of her husband and near relatives, the client donated a part of her land for a mosque to be built. A temporary structure was erected. After her death, her grand-daughter, an architect, acted on her behalf as fundraiser, designer, client and builder to bring the project to completion.

In an increasingly dense neighbourhood of Dhaka, the mosque was raised on a plinth on a site axis creating a 13-degree angle with the qibla direction, which called for innovation in the layout.

A cylindrical volume was inserted into a square, facilitating a rotation of the prayer hall, and forming light courts on four sides. The hall is a space raised on eight peripheral columns.

Ancillary functions are located in spaces created by the outer square and the cylinder. The plinth remains vibrant throughout the day with children playing and elderly men chatting and waiting for the call to prayer.

Funded and used by locals, and inspired by Sultanate mosque architecture, it breathes through porous brick walls, keeping the prayer hall ventilated and cool. Natural light brought in through a skylight is ample for the daytime.

Issam Fares Institute, Beirut, Lebanon by Zaha Hadid Architects

The American University of Beirut (AUB) held an invited competition for the design of a structure to accommodate a modern-day think tank on its lush middle campus – one that was in harmony with the rest of the university, especially mindful of the surrounding greenery, and to preserve as far as possible existing sightlines to the Mediterranean.

The building had to fit into another stage in the implementation of a master plan for AUB, whose upper campus overlooks the water and whose lower campus is located on the seafront.

The architect responded to the project brief by producing a design that significantly reduces the building's footprint by "floating" a reading room, a workshop conference room and research spaces above the entrance courtyard in the form of a 21-metre-long cantilever in order to preserve the existing landscape.

The 3,000-square-metre building is defined by the routes and connections within the university; the building emerges from the geometries of intersecting routes as a series of interlocking platforms and spaces for research and discourse.

The massing and volume distribution fits very well with the topography, and the nearby Ficus and Cyprus trees are perfectly integrated with the project. The building's construction is a continuation of the 20th-century Lebanese construction culture of working with fair-faced concrete.

Cha'er Hutong Children's Library and Art Centre, Beijing, China by ZAO, standardarchitecture and Zhang Ke

Cha'er Hutong is a quiet spot one kilometre from Tiananmen Square in the city centre. Number 8 in this neighbourhood, located near a major mosque, is a typical da-za-yuan (big messy courtyard) once occupied by over a dozen families.

The courtyard is about 300-400 years old and once housed a temple that was then turned into residences in the 1950s. Over the past 50 or 60 years, each family built a small add-on kitchen in the courtyard. Almost all of them have been wiped out with the renovation practices of the past years.

In redesigning, renovating and reusing the informal add-on structures instead of eliminating them, it was intended to recognise them as an important historical layer and as a critical embodiment of Beijing's contemporary civil life in hutongs that has so often been neglected.

In concert with the families, a 9-square-metre children's library built of plywood was inserted underneath the pitched roof of an existing building. Under a big Chinese scholar tree, one of the former kitchens was redesigned into a 6-square-metre miniature art space made from traditional bluish-grey brick.

Through this small-scale intervention in the courtyard, bonds between communities have been strengthened and the hutong life of local residents enriched.

Friendship Centre, Gaibandha, Bangladesh by Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury of URBANA

The centre was created to train staff of an NGO working with people inhabiting nearby chars, or riverine islands. Offices, a library, meeting rooms, and prayer and tea rooms are included in pavilion-like buildings that are surrounded by courts and pools.

The centre is also rented out for meetings, training, and conferences for income generation. The local hand-made brick construction has been inspired by the monastic aesthetic of the 3rd century BC ruins of Mahasthangahr, the earliest urban archaeological site yet found in Bangladesh.

Structural elements are made of reinforced concrete and finishes include timber and stone. The naturally ventilated structures have green roofs. The centre is located in an agricultural area susceptible to flooding and earthquakes, and whose low-bearing soil has a low bearing capacity. As a result, an embankment has been constructed with a water run-off pumping facility.

Constructed and finished primarily of one material – local hand-made bricks – the spaces are woven out of pavilions, courtyards, pools and greens, corridors and shadows.

The Friendship Centre is divided into two sections, the outer Ka block for the offices, library and training classrooms and the inner Kha block for the residential section. Up to 80 people at a time can be trained here in four separate classrooms. Simplicity is the intent, monastic is the feel.