"The Global South could create a different, and maybe better, kind of modernity"

Chile and Cuba's contributions to the London Design Biennale suggest that, while the Global South is expected to copy the design of the north, it could offer a more radical future, argues Owen Hatherley in his latest Opinion column.

The once-again fashionable topic of "utopia" was the theme of the first London Design Biennale, held until a couple of weeks ago in the sprawling Georgian office block of Somerset House.

The only thing as fashionable today as utopia is informality, particularly when it comes from the Global South, so the winner of the best pavilion went to Lebanon, for Annabel Karim Kassar's project Mezzing in Lebanon, which recreated part of a Beirut street on the terrace of Somerset House.

The only thing as fashionable today as utopia is informality

While overlooking the Thames you could get a fix of the sights and smells of the souk, have yourself some street food, admire some daring film posters and lie on a divan, all without leaving WC1. Utopia there is the street, always vibrant, with ordinary people creating their urbanism themselves, always apparently without any mediation.

There were two other projects that set themselves much more ambitious tasks, while similarly coming from what would be broadly considered the global periphery – the exhibits of Cuba and of Chile, both of which were about the links between design, intangible electronic networks, and their presence in real space.

The Chilean exhibit, The Counterculture Room, was curated by FabLab Santiago on the subject of something called Project Cybersyn, or as it was known in Spanish, Projecto Synco. This was an apparently wildly overambitious attempt to create a sort of socialist proto-internet, instigated by the leftist Popular Unity government of Salvador Allende. It had barely a chance to be implemented before the government was overthrown in a violent, CIA-instigated military coup on September 11, 1973.

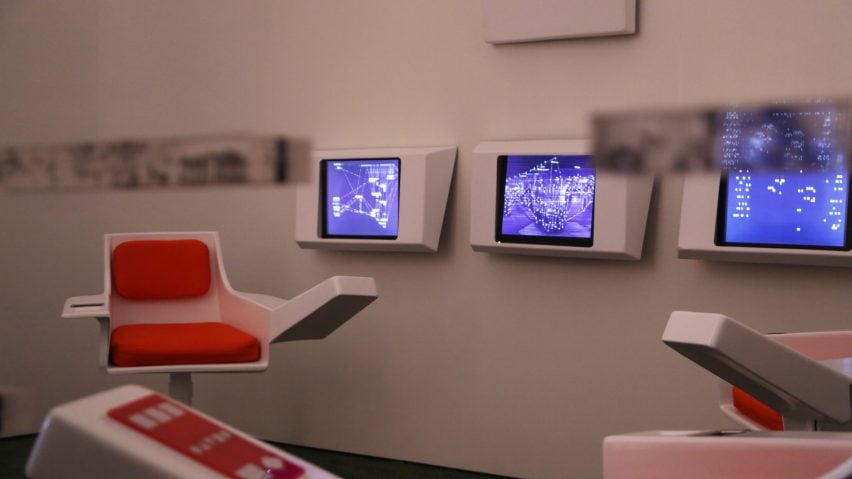

This has become a bit of a cult in recent years, usually via a photograph of its control room. Designed by Gui Bonsiepe of the State Technology Institute – the organisation created under Allende to mass produce accessible consumer goods for the Chilean working class, such as the peculiar Citroen Yagan car – the control room consisted of white fibreglass chairs with orange cushions in a circle, in a style with some affinities to Verner Panton and to the set designs for 2001: A Space Odyssey. Behind these space-age swivel chairs are screens showing production statistics.

It is an exciting if slightly sad experience to step into the control room and take a selfie

In the last few years, photographs of this space have become icons of the semi-serious internet meme Fully Automated Luxury Communism – fragments of the idea that cybernetics and networks could actually be claimed by a radically democratic left, rather than the libertarian right.

It is, then, an exciting if slightly sad experience to step into the control room and take a selfie. It's every bit as fake as the Lebanese "street" outside, but here, rather than being taken to a real street, you're taken to a real future that never happened. Around the room, little reels of photographs show images from the brief, tragic three years of Chilean socialism, and a documentary tells the story. But everything revolves around the room.

In Cybernetic Revolutionaries, her recent book on the project, Eden Medina makes clear that this apparently ultra-high-tech space was actually quite an ad-hoc, improvised project. Resulting from a collaboration between the British cybernetician Stafford Beer and Allende's Minister of Finance Fernando Flores, it used a couple of the (very few) mainframe computers in early 1970s Chile and linked them to the more extensive telex network. In theory, Cybersyn would connect up the newly publicly owned factories of Chile to a fast, computerised control system, which would save it from the sclerosis of the Soviet command economy; it was used once, to help break a strike of lorry drivers.

Medina finds that, at the time, many on the left were afraid of Cybersyn, seeing it as a kind of cyber-Stalinism, a computerised Big Brother. It was only many years after the Pinochet government literally destroyed the project, and the room with it, that Cybersyn gradually came to be reassessed by a new left immersed in the internet.

Fans of the apparently decentralised networks of the internet can see the Control Room as their tragic, unfulfilled precursor

The big controversy is whether that Control Room – that sexily designed, achingly cool space – was going to centrally control the production process, or whether it was a means for Chilean workers to send signals to the government. Beer and Flores – and Allende – argued the latter. We'll never know, but fans of the apparently decentralised networks of the internet can see it as their tragic, unfulfilled precursor.

But what the curators emphasise in The Counterculture Room is the implications of Cybersyn for the relationship between poor and rich countries. Sitting in a Santiago office with a view of a Gothic cathedral, Gui Bonsiepe laments how the south is perennially expected to copy, belatedly, the technologies and aesthetics of the north. Cybersyn reversed the process, creating Chile's own cybernetic network in the face of innumerable criticisms that such things were only possible in the USA.

The Cuban exhibit in the Biennale, Parawifi – Humanising the City, curated by Luis Ramirez and Miguel Aguilar, is predicated on this being impossible, but on it also being something that can be improved and designed. The relationship between Allende's Chile and Fidel Castro's Cuba was uneasy – after a visit, troubled by the Chileans' insistence on openness, gradualism and democracy, Castro declared: "No social system has ever resigned itself to disappearing through its own free will... I will return to Cuba even more of an extremist than when I came here."

It argues that the future is in the south

The bloodbath that resulted from Allende's overthrow might seem to have borne him out. Over 40 years later, Cuba is still, officially at any rate, socialist, but ultra-advanced schemes for cybernetic communism have not been what has kept the place afloat. Today, it is admired more for the extent of its organic agriculture, an improvised response to the withdrawal of preferential Soviet trade deals in the 1990s.

In terms of design, Parawifi isn't a world away from Project Cybersyn, another set of plastic, Pantonesque, brightly coloured, lightweight structures for sitting in – cute, chic and a tad retro. It is a system of seating cubes, designed to be assembled and disassembled in public space, each with a power source so that people in Havana can plug in their smartphones and use them comfortably in the blazing heat. As in the Chilean and Lebanese pavilions, there's a little mock-up you can sit in.

Crucially, it doesn't suggest the creation of a new network, assuming that mobile telephony will presumably go on being largely controlled by western multinationals, but proposes instead a way of building the internet into a pleasurable, comfortable bit of public space. In so doing, it confronts some of the same issues that Project Cybersyn once did, but with the ambitions trimmed somewhat. Still, it argues that the future is in the south, not as a soulful holdout of good food and vibrancy, but as a place that could create a different, and maybe better, kind of modernity.