With his stadium for the 2020 Olympics now underway in Tokyo, Kengo Kuma has revealed how his design involves Japan's tsunami-affected regions, how Kenzo Tange inspired his work, and why he now avoids iconic architecture at all costs.

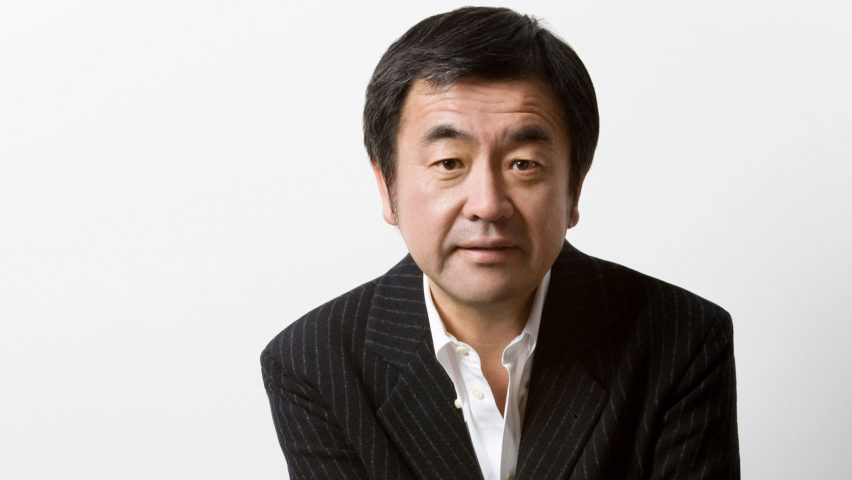

Kuma, 62, is among a number of prolific architects working in Japan at the moment, but is particularly well-known for his use of wood, on projects such as his Garden Terrace Nagasaki hotel in southwest Japan and the Yunfeng Spa Resort in China.

However, the architect's early career was dominated by projects that were more experimental in style and form – the most radical example being his postmodern M2 Building, which reads as a mishmash of different architectural styles.

In an exclusive interview, Kuma – who ranked at number five on the Dezeen Hot List – said he now avoids this type of architecture all together.

"To be honest, sometimes I feel a bit embarrassed by some of my buildings," he said.

"My method is to avoid heroic gestures, because you get to a point where the heroics kill the beauty of the material," he added.

"I want to find a balance expressing form and material. The form of the building should be as subtle as possible, because then the material's character can reveal itself."

This approach is best illustrated by the stadium that Kuma has designed for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games: a wooden arena, with plants and trees filling the terraces that make up its exterior walls.

It is a far cry from the more sculptural design created by Zaha Hadid, which won the original design competition but was controversially scrapped by the Japanese government after two years of development.

It will also stand in striking contrast to the curved concrete arena that Kenzo Tange designed when the city last hosted the games, back in 1964. Kuma said that Tange's work inspired him to become an architect – but that he decided not to follow the same path.

"The Olympic Stadium designed by Kenzo Tange showed the success and economic power of the last century by using concrete and steel," he said. "My own design reflects a different time and different needs."

"I believe concrete and steel were the materials of the previous century, and the key material for the 21st century will be wood again, he said.

Wood used to construct the stadium will be sourced from parts of Japan affected by the devastating earthquake and tsunami of 2011, according to Kuma, and help create a building with a human scale.

"It is oriented horizontally, its silhouette is as low as possible, and key structural parts are small and made of wood," he said. "Its size is closer to the human body, and there is a clear reference to the current situation in Japan."

Read on for the full interview conducted by Filip Šenk, reporting for Dezeen from the Czech Republic.

Filip Šenk: Your architecture has a lot of respect for tradition. But tradition is a broad term. Could you explain what specifically it is that you appreciate about tradition?

Kengo Kuma: Tradition for me is a history of construction. I'm very interested in the technique and technology of making a building. Most of the history of architecture is about the changing styles of architecture. But behind the change of style, there was often a change of construction method and changes in the way material was used. Especially in Japan, before the concrete technology that came from Europe and the USA, we had a very long tradition of wooden buildings.

In Japanese wooden buildings, technique and style are very much related. I studied changes in technology, and it gave me many hints for my designs.

I'm very interested in the technique and technology of making a building

Wooden buildings and concrete buildings are totally different from each other. Of course, it is not only the essential material but the life of the building that is very different. For wooden buildings, ageing is very important. With wooden buildings, we are able to design the process of its ageing. But with concrete buildings, people seem to forget the ageing of the material.

Concrete is actually not as permanent a material as it appears to be. And we can see it clearly nowadays, because there are big problems with modernist designs. Traditional Japanese buildings have a very smart system of replacing materials. An ancient wooden temple is still very alive because of this system of replacing. But with concrete buildings, you cannot replace the parts.

For my own buildings, I would like to have a similar system of reconstruction or replacing with a new technology. That is the reason why we combine wood with carbon fibres, for example.

Filip Šenk: But modernism has also become part of the heritage of Japanese architecture, and Kenzo Tange in particular, with his stadium for the 1964 Olympics. And now you're following in his footsteps, with your stadium for the Olympics in 2020. Do you find inspiration in Japanese modernist architecture, and in the work of Kenzo Tange?

Kengo Kuma: Kenzo Tange and the buildings he designed are one of the reasons why I became an architect. Above all, I think I was influenced by his method. He studied the Japanese tradition very deeply and learned many things.

I also studied traditional buildings, although the character he found in traditional buildings was different from the one I found. He learned a great deal about the vertical line and its symbolic position, but I didn't want to use that. He appreciated and respected tradition, and I also have a lot of respect for tradition.

Kenzo Tange and the buildings he designed are one of the reasons why I became an architect

Filip Šenk: Respect for tradition can easily be seen in your designs dating back to the early 1990s. It has a completely different form, however – it is more like postmodern architecture, with oversized parts like Ancient Greek columns. How do you view those works now?

Kengo Kuma: To be honest, sometimes I feel a bit embarrassed by some of my buildings. I studied the history of architecture and discovered that the basis for the European and American architecture tradition was in fact Ancient Greek and Roman architecture.

Later, when I studied at Columbia University in New York City, I realised through discussions with my Americans friends that I should study Japanese architecture because I'm Japanese. In America, they have great knowledge of European architecture, but as I studied Japanese architectural history, I found depth that one could view as equal to that of the European and American history of architecture. I realised that traditional Japanese wooden architecture is as great as Ancient Roman architecture. And that's actually the result of my American experience.

Filip Šenk: When you talk about construction, it is a more material view. Could you tell me more about your interest in the immaterial part of architecture, and how you handle light and space?

Kengo Kuma: Shadow is a very important part of my designs. A good example is the new Olympic Stadium. In section it has many levels, with trees to create shadows, but also to protect the wood from natural light and rain.

The shadow is aesthetically very important, but there are also technical reasons for it. I believe concrete and steel were the materials of the previous century, and the key material for the 21st century will be wood again.

Shadow is a very important part of my designs

The Olympic Stadium designed by Kenzo Tange showed the success and economic power of the last century by using concrete and steel, and that is also why the vertical line is so strongly present there. My own design reflects a different time and different needs; it is oriented horizontally, its silhouette is as low as possible, and key structural parts are small and made of wood. Its size is closer to the human body, and there is a clear reference to the current situation in Japan; the wood comes from various areas in Japan, but mainly from areas devastated by the tsunami in 2011.

Filip Šenk: I've heard you say before that you don't like to do big and heroic gestures, even with large structures. Can this idea work in the case of an Olympic stadium?

Kengo Kuma: My method is to avoid heroic gestures, because you get to a point where the heroics kill the beauty of the material. I want to find a balance expressing form and material. The form of the building should be as subtle as possible, because then the material's character can reveal itself. If the balance is there, it's beautiful.