Brazil's dictatorship caused lasting damage to architecture education, says Paulo Mendes da Rocha

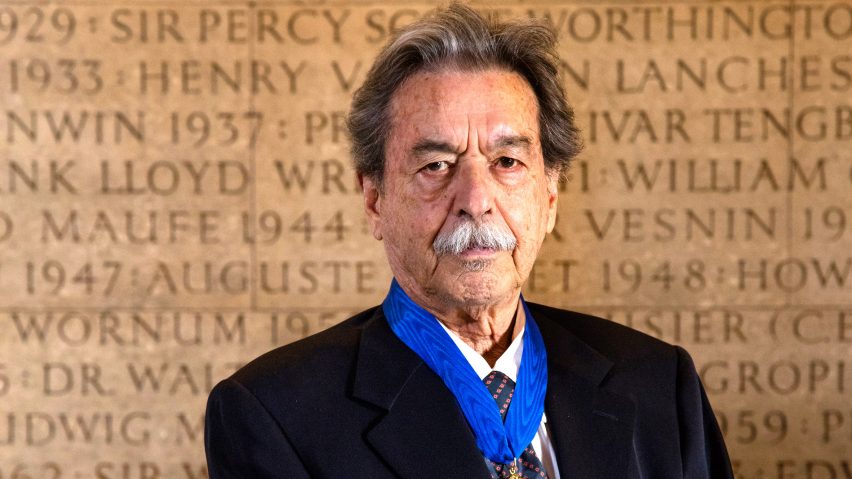

Destroying architecture education was the "greatest evil" performed by Brazil's military dictatorship, according to Brazilian architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha, who has just been awarded the Royal Gold Medal.

Mendes da Rocha, 88, told Dezeen that Brazil's military coup in 1964 and the resulting 20-year dictatorship not only had a significant impact on his early career, it caused lasting damage on the country's architecture.

He described the regime's restriction on education as it's "greatest evil" and said that Brazilian architecture is still struggling to undo its effects.

"The military coup was a very right-wing dictatorship and it was a very violent one as well," said Mendes da Rocha, during an exclusive interview.

"I could say that it has destroyed education and universities in Brazil before they did anything. And up to today we're still suffering from the consequences of those actions, and we're working very hard to catch up and recover what we had," he continued.

"This would be the greatest evil performed by the military coup, more over than any individual issues."

Mendes da Rocha set up his São Paulo-based practice in 1955 and completed the now-iconic Athletic Club of São Paulo just two years later.

But, following the coup, he was banned from teaching and practicing in his own right, as were other left-leaning colleagues.

He said that many younger architects are unaware of the consequences of the regime, and that political unrest and war is the world's greatest threat to education.

"They're not aware of what has been done, I think this is the greatest issue," said Mendes da Rocha. "To rebuild all this is not just a Brazilian issue, I would say that is a global issue, because in some ways Brazil's just a small example of what has happened world-wide in the 20th century with wars."

"It [war] affects the development of knowledge and education, but on the other hand we can say it's a common human condition we're experiencing."

He said that architecture schools needs to encompass a much greater breadth of knowledge, rather than just built form.

"Architecture deals with all forms of human knowledge – anthropology, criticism, philosophy, linguistics, techniques," he said. "I have the impression that at the heart of a university, the school of architecture can be the central nucleus of all knowledge."

"Maybe the most striking peculiarity of architecture is that] when we build something we are building the city. Spatial transformation happens with this act of building."

Paulo Mendes da Rocha is prolific in his native Brazil – with projects including the Estádio Serra Dourada in Goiás (1975), the Forma Furniture showroom in São Paulo (1987) and the Saint Peter Chapel in São Paulo (1987) among his most prestigious. But he has also completed just a handful of buildings overseas.

Among them is the 1970 Osaka Expo pavilion and the recently completed National Coach Museum in Lisbon – a project he says holds special significance for him.

Situated to the rear of Amanda Levete's MAAT museum in the city's historic Belém area, the stretch of coastline it is situated on is said to be where the first ships set sail to Brazil.

"Sailing ships left from there and they discovered Brazil. So it's a great emotion, its incomparable," he said.

"The emotion, the gratitude, the beautiful, the peculiar beauty of each project is something incomparable. They are all very grandiose emotions."

Paulo Mendes da Rocha was awarded the Royal Gold Medal by RIBA president Jane Duncan in a ceremony this evening.

The award recognises the architect's lifetime achievements, and adds to his growing cache of the world's most prestigious architecture accolades. Among them are the Mies van der Rohe Prize, which he was presented with in 2000, the Pritzker Prize in 2006, and in 2016 the Venice Biennale Golden Lion and the Praemium Imperiale International Arts Award.

Duncan, who describes Mendes da Rocha as a "living legend", said: "Paulo Mendes da Rocha's work is highly unusual in comparison to the majority of the world's most celebrated architects."

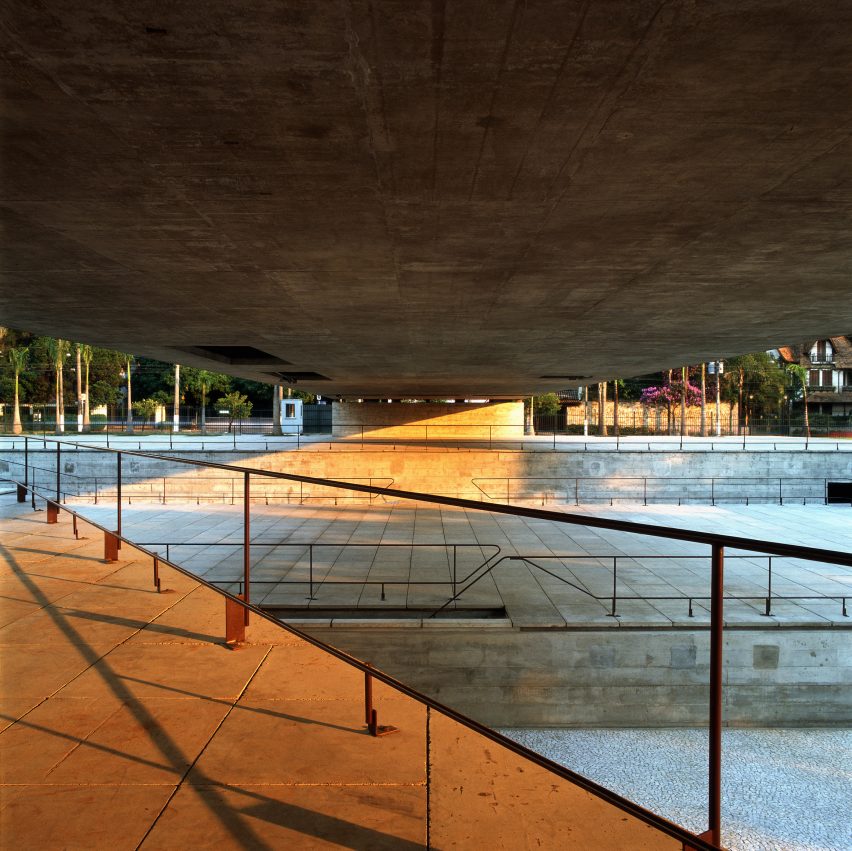

"He is an architect with an incredible international reputation, yet almost all his masterpieces are built exclusively in his home country," she added. "Revolutionary and transformative, Mendes da Rocha's work typifies the architecture of 1950s Brazil – raw, and beautifully crafted concrete."

The bold forms and chunky coarse-grained concrete walls that are characteristic of his work have often drawn parallels with British Brutalism.

On receiving the award Paulo Mendes da Rocha said: "I didn't aim for the award – but I see it as a beginning of a reflection to which I have contributed to. It's an eternal reflection about what to do with nature in order to make the planet habitable."

Last year's Gold Medallist was the late British-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid, who received the prize just one month before her death. Hadid became the first ever female architect to win the award in her own right in the Gold Medal's 180-year history.

Past recipients include fellow Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer, Frank Gehry, Norman Foster and Frank Lloyd Wright.