Although projects by OMA and BIG have come close, we're still a way off realising "sublime" architecture through generic building forms, says Aaron Betsky in his latest Opinion column.

Can the absolutely normal and everyday be beautiful? Two recent books claim it can be. They take standard, interchangeable building blocks of the kind we see everyday – suburban houses, office buildings, and apartment blocks – to construct a human-made landscape they hope will evoke a sense of wonder.

One of the two, The Generic Sublime, by Ciro Najle, uses computer technology to develop landscapes unfolding into structures of a huge scale.

The other, Atlas of Another America, by Keith Krumwiede, starts from suburban house plans and combines them into mythical subdivisions. If in the end it is hard to believe in either Najle's or Krumwiede's proposals, that does not make them any less compelling.

Najle's thesis, developed through several years of teaching studios at Harvard's GSD, is an ambitious one, and one that he sees as continuing the work of the Beast Master of Banality, Rem Koolhaas. Najle says:

The result, he says, would be "optimistic" and a "second nature", which is in line of what both those who study large-scale development and those who advocate computer-generated form claim for their work.

Najle's students' work proceeds from diagrams to landscapes that are most intriguing when they consist of towers whose bases melt into the landscape and then sprout up new versions of themselves, or nests of apartment slabs whose endless crossing and re-crossing leads the eye towards the distance.

Grids of either office or apartment blocks reproduce seemingly automatically, according to the computer's programs, while constructions of a more sinuous persuasion snake along what appear to be contour lines of an invented landscape.

The forms are beautiful, but they also look familiar, recalling the products that have come out of Koolhaas' Office for Metropolitan Architecture and its offspring, such as BIG, over the last decade.

It is no wonder that students look towards such heroic producers of what are indeed banal bits and pieces stacked up, deformed, or blown up in scale. But what neither they nor their professor seem to catch is exactly the manipulation, which is altogether willful and not generic, that cracks these forms open to produce a sense of wonder as, for instance, you look up or down the stacked terraces of Koolhaas' Seattle Public Library or the curve of BIG's VIA 57 West apartment building.

Krumwiede, by contrast, starts small and old-fashioned. After analysing an array of developer plans for suburban homes, Krumwiede comes to the conclusion that the four-square plan of an entry with guest bath, living room, dining room and kitchen, with bedrooms above, around a circulation core – the basic American house plan of the period right after the second world war – has over the last few decades spun out not into just endless variations, but first into two types, namely Laminar (Wide) and Laminar (Deep) that add both ancillary spaces and square footage to the dwelling.

These are then divided into the Cellular, Nuclear, Bisected, and Branching plans, each of which adds more spaces and complexity. Diagonals move out to control some of that sprawl, as do central halls that can become round or octagonal.

As these plans metastasise, they also increase in cost, from what Krumwiede says is about $119 (£95) for the Four-Square to $198 (£158) for the Branching type.

Krumwiede's result is something closer to a "generic sublime" than the landscapes of Najle

Then this author breaks one cardinal rule of American subdivisions: he combines each of the plans separately into rows, blocks, pinwheels and other geometric groupings. They lose their vestigial side yard separation, as well as their – in truth often also nominal – private front and rear yards.

Instead, they become compounds around and in shared open space with names such The Citadel at Filarete Fields, Robin Hood Gardens, and Le Ville Rotunde, whose names recall both the plans' architectural pretensions and the grandiloquent names developers give to their creations.

Next, Krumwiede proposes that each of these blocks find its place in a "section": the mile-square grid that makes up the basic unit within the National Land Ordinance of 1785 (the Jeffersonian Grid) that divided up the United States.

He arranges them into larger groupings that together he calls Freedomland: settlements in some unknown, flat expanse where the inhabitants of the blocks will farm and hunt, but also have big box retail stores and other modern conveniences.

The whole is a combination of a nostalgic vision of living on the land, as Thomas Jefferson once hoped all Americans would, while have all modern conveniences that we expect in suburbia.

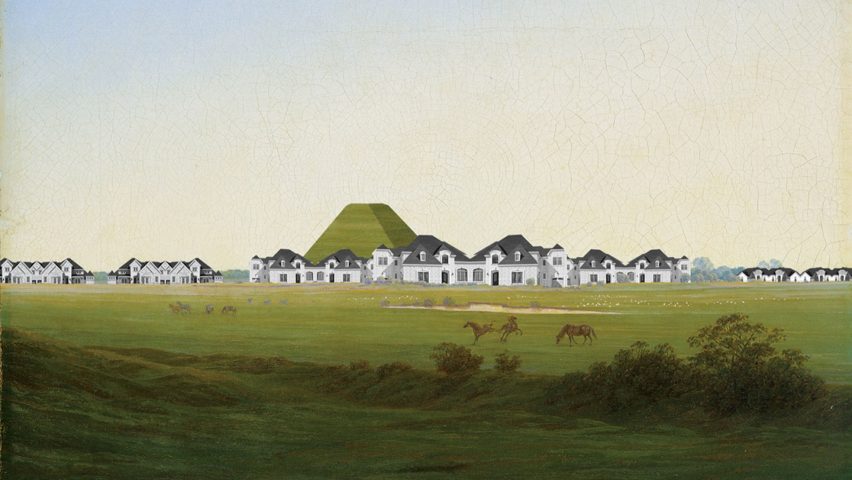

Krumwiede finishes and sauces his vision by describing the scheme with texts that evoke the language of 18th and 19th century utopian proposals. He then raids art history, cribbing paintings by the likes of Winslow Home, Millet, and Claude Le Lorrain, collaging his house plans into their visions of verdant splendor.

This veneer might not quite prove Freedomland's potential sublimity, but it does present us with a vision of American suburbia ennobled, enhanced, and enlarged to the point that it looks pretty darn attractive.

For now, the generic remains in its banality

When combined with the intricacy of the geometries Krumwiede mines from the combination of the house plans, the result is something closer to a "generic sublime" than the landscapes Najle and his students spun out of their computers. Not only that, but Krumwiede's research is invaluable, not least for taking an area overlooked by almost every architect seriously and trying to figure out what makes it work.

Both schemes have, in my opinion, one major failing that keeps them from living up to their similar, though differently pursued, goals: they refuse to accept the social and economic logic behind the generic building blocks from which they start.

Krumwiede's avowedly mythic vision assumes a world in which we will somehow give up our absurd desire for our very own mansion, no matter how mass produced, while Najle and his students spin recognisable buildings into fantastical piles and landscapes whose very presentation in black lines on white paper (or screens) are too abstract to be real.

For now, the generic remains in its banality, leaving our boxes of absence in soulless sprawl to spread all around us. The sublime images are just mirages that are destined to remain in books. I hope that, in continuing to explore their methods, either Najle or Krumwiede can figure out how to make something astonishingly real out of that sprawl that goes beyond their modest, if mordant and intriguing, proposals.