With her latest exhibition, British artist Laura Oldfield Ford is more likely to change your understanding of London's working-class landscape than any architect or designer, says Owen Hatherley in this Opinion column.

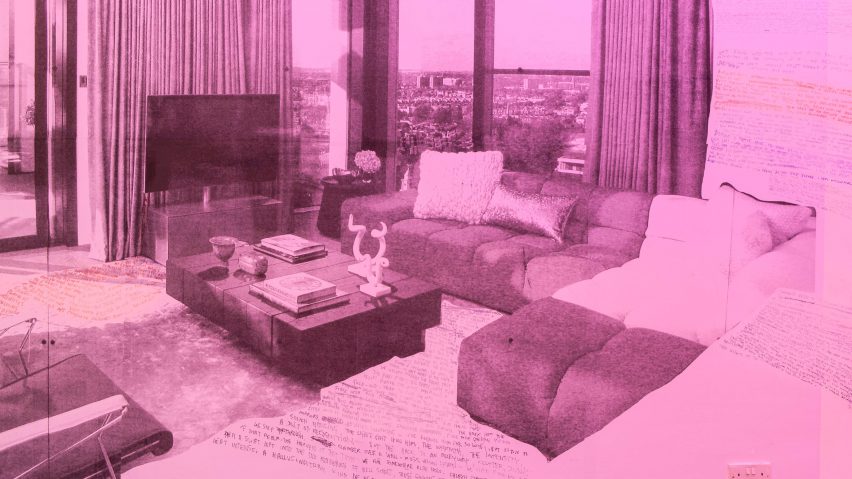

At the far end of Laura Oldfield Ford's exhibition Alpha/Isis/Eden – on at the Showroom Gallery in Lisson Grove, just northwest of central London – is an image taken from a property brochure for a recent building in the area.

It's a view of an interior, of a very familiar kind. The room is small, but expensive furnishings and a view manage to obscure that fact. Vaguely modernist lightweight chairs, a plush sofa, a coffee table with design books and objets d'art frame what you can see through the floor-to-ceiling windows – which you'll notice, if you've just wandered around the area, is an aerial view of where you are, with the spire of John Soane's Holy Trinity Marylebone as a marker ("occupied", we'll learn, "by an American evangelist sect").

Multicoloured writing is scrawled between the angles of this clean-lined space, and the colour has been tinted, making it look queasy, radioactive. What is happening here is a conjuring act – an attempt to call back all that this image of a perfect high-rise room for sale erases. All the forgotten moments, fervent hopes and lost connections that these ubiquitous photos and renders of mediocre super-modernity suggest have definitively disappeared are brought back, albeit fleetingly.

For the last 10 years, Oldfield Ford has tried to maintain the presence of a barely remembered London

For the last 10 years, Oldfield Ford has tried to maintain the presence of a barely remembered London of squats, council estates and picket lines, a place all but wiped off the face of the earth by property prices, through her work as a painter and writer, particularly in her zine Savage Messiah, which was collected into a book by Verso in 2011, in time for the riots it predicted.

The average issue of Savage Messiah took a particular part of London – the Westway, Kings Cross, Stratford, Heathrow, to name a few – and collaged, scribbled or typed memories of it, both her own and others. It would include distorted photographs, property renders and, particularly memorably, her own densely wrought counter-images, often meticulously cross-hatched in biro, of waste-strewn industrial sites, dilapidated Victorian squats, industrial estates, heroic concrete engineering, and GLC housing estates with their labyrinthine walkways and hiding places (a disaster for planners and architects since the 60s, because they are so hard to patrol and police, and an ideal landscape for Oldfield Ford for exactly the same reason). Within these would be endangered 80s subcultural tribes of anarcho-punks, skinheads and rude boys, treated by Oldfield Ford treats as almost angelic figures, but whose places are now taken by the grinning, glass-clinking figures on the billboards.

It was the sort of thing easily caricatured as sentimental by those who think everything is wonderful as it is. But the lament in Savage Messiah is not merely about how great London was when the rich were confined to an enclave in Mayfair-Belgravia-Kensington and bankers lived in Surbiton rather than Peckham. It's a matter of what her ghostly figures didn't manage to do – to transform London into a new kind of city, one where work barely exists, property is irrelevant and everywhere can be walked. Their hopes were thwarted and so, in her collages, they haunt 21st century London instead. But traces of them can also be found in the present – something the zine did its best to record.

This is an immersive environment – the closest this enthusiast for Brutalism will ever come to architecture

What Alpha/Isis/Eden (named after three local high-rises under threat of demolition) does is a little different. Earlier exhibitions have often been of paintings and drawings, but this is an immersive environment – the closest this enthusiast for Brutalism and relentless opponent of rational town planning will ever come to architecture. And it's in the perfect place for it, a part of inner London which hasn't quite been crushed yet.

Much of the area is extremely wealthy (and an earlier architectural response – Tony Fretton's early, elegant, Platonically austere Lisson Gallery – is a reminder of art's role in that transformation), but the density of council estates and Peabody tenements built there between the 1870s and 1970s means that signs of working class metropolitan life – cafes, launderettes, an unpretentious street market, a multicultural population – are still to be found.

The entrance to the Showroom has dense text pasted over it: "I could trace paths through the squats of Elgin Avenue, the acid house parties beneath the Westway....strange constructions emerging from heaps of scrap metal...the Acklam Hall, crepuscular worlds of dreaming and drifting". Inside, the ground floor is turned over into full-height blow ups of collages of property ads, drawings and snapshots of estates, underpasses and the nearby Marylebone flyover, covered in text, sometimes encrypted, sometimes suddenly clear. Minions make several unexpected appearances. Metal grille doors, of the sort used to deter squatting, are placed around to frame these. The text carries the original disclaimer "lifestyle images are indicative only".

The most striking addition is the sound – an hour-long composition by Jack Latham, better known as Jam City. The result is psychedelic, a montage of her readings, snippets of luxury apartment marketing patter, the sounds of the street around, drones and rumbles of bass, and snatches of the dizzy electro-soul showcased on his album Dream a Garden.

After leaving, you see where you are completely differently

After a time – and it takes time – in this space, the sound and the images melt together. Oldfield Ford's soft West Yorkshire tones contrast with the oblique but violent words edged into the landscapes: ZONES OF SACRIFICE; THE WESTWAY HAS ALWAYS BEEN THERE; LISSON GREEN MAN DEM; LONDON HAD SNAPPED AWAKE. ALL THOSE DORMANT STRANDS, HIDDEN CURRENTS EXPOSED.

After leaving, you see where you are completely differently, your mental topography altered and filtered in a way that the heritage culture tropes of "psychogeographic" writing no longer can.

Architects and designers are not good at this. The past means "context" and "reference", politics is "consultation", modernism becomes the affirmation of what is. Through this, an enormous amount has been repressed – things you're not meant to think about, lest they complicate the brief, or suggest that the brief itself is fundamentally corrupt.

Alpha/Isis/Eden is all about those things that even professedly "radical" architectural practices find it impossible to work with. In a small space, it creates an environment suffused with anger, memory, longing, vengefulness and solidarity, in a city that is trying to force those emotions, and the people who hold them, out.

Photograph is by Daniel Brooke.