Design Museum's Imagine Moscow exhibition explores six unbuilt Soviet landmarks

Six radical designs for the Moscow skyline – proposed in the wake of the October Revolution, but never built – are showcased in an exhibition opening today at London's Design Museum.

The exhibition Imagine Moscow marks the centenary of the Russian Revolution by dusting off six shelved proposals for architecture in the newly formed Soviet Union, including what would have been the world's tallest skyscraper.

Dating from the 1920s and 1930s, the schemes show the impact of the union's socialist ideology on the work of architects like El Lissitzky and Konstantin Melnikov. Each of the schemes centres around Moscow's Red Square, the city's central plaza.

Drawings, models and projections of the six proposals are presented alongside constructivist and suprematist artworks and designs from the era.

"The October Revoluton and its cultural aftermath represent a heroic moment in architectural and design history," said exhibition curator Eszter Steierhoffer.

"The designs of this period still inspire the work of contemporary architects, and the radical ideas in the exhibition remain highly relevant to cities today.

"Imagine Moscow brings together an unexpected cast of 'phantoms' – architectural monuments of the vanished world of the Soviet Union that survive in spite of never being realised," she added.

Imagine Moscow is on show at theDesign Museum until 4 June 2017. Here's an overview of the six unbuilt projects it features, in roughly chronological order.

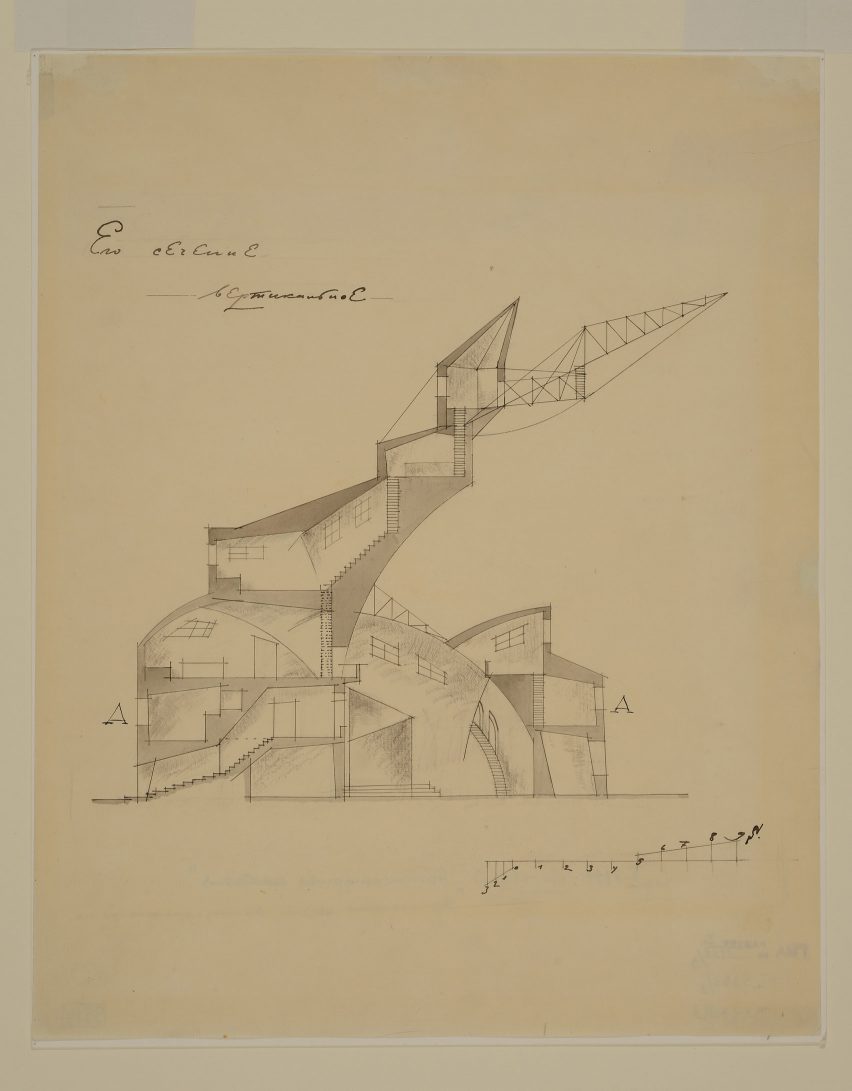

Communal House by Nikolay Ladovsky (1919-20)

Ladovsky's Communal House included shared facilities like nurseries and kitchens that aimed to lighten the workload for Soviet women – freeing them up to devote time to self improvement and to work.

The scheme was part of a wider attempt during the period to induce communal housing and amenities that would break down the traditional family unit.

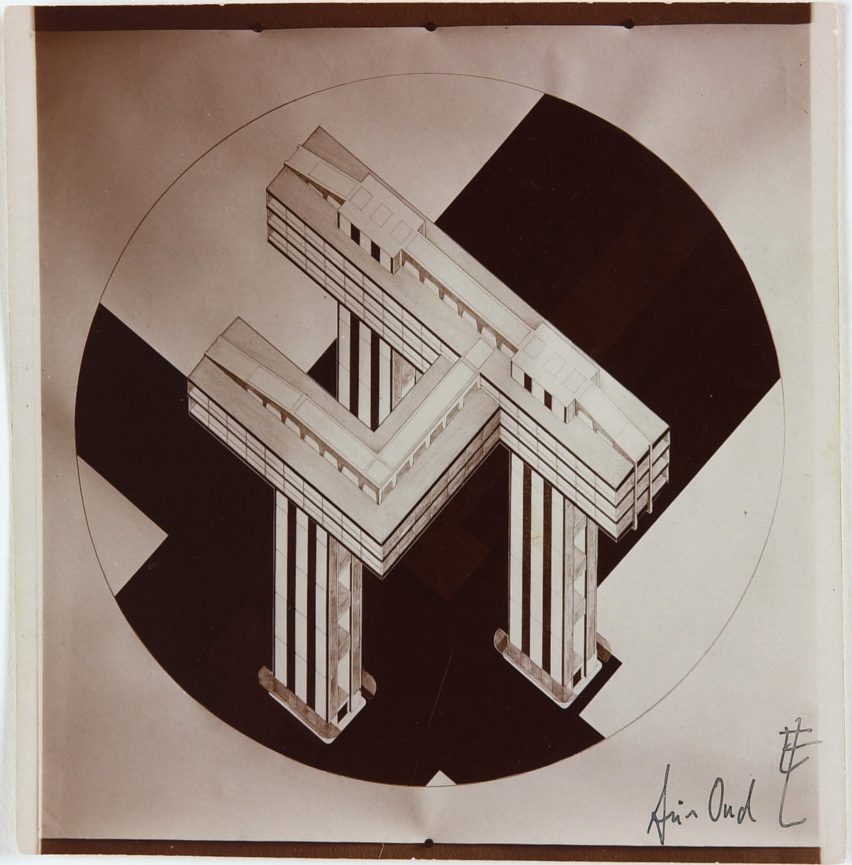

Cloud Iron by El Lissitzky (1923-25)

Lissitzky pitched his network of eight horizontal skyscrapers for Moscow's Boulevard Ring. The top heavy blocks – placed horizontally on top of vertical towers – aimed to maximise a relatively limited footprint.

The horizontal blocks were to contain offices and apartments, which would be linked with metro stations and tram stops at street level by the upright towers.

Lenin Institute by Ivan Leonidov (1927)

A huge sphere would have hosted an auditorium at Leonidov's Lenin Institute, with a slender tower to its rear containing 15 million books split across five reading rooms.

The complex would have also contained a planetarium and science lecture theatres, broadcasting events to the rest of the world by a radio station.

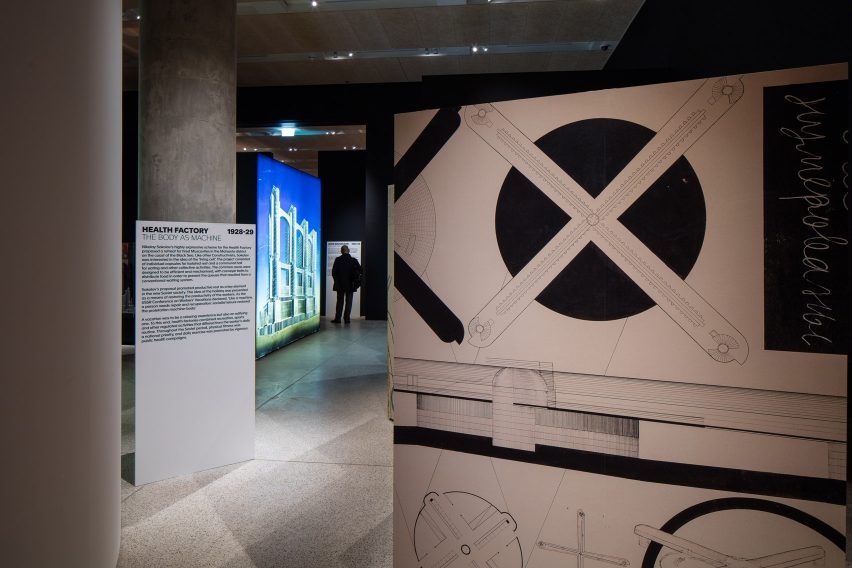

Health Factory by Nikolai Sokolov (1928-29)

Sokolov's design for a retreat on the Black Sea coast is intended to provide respite for weary city dwellers.

Individual rest pods were coupled with communal dining and activity spaces in the scheme, which aimed to improve the productivity of workers on their return to Moscow. Features included a dining hall where food was to be distributed by conveyor belt to do away with the street of queuing.

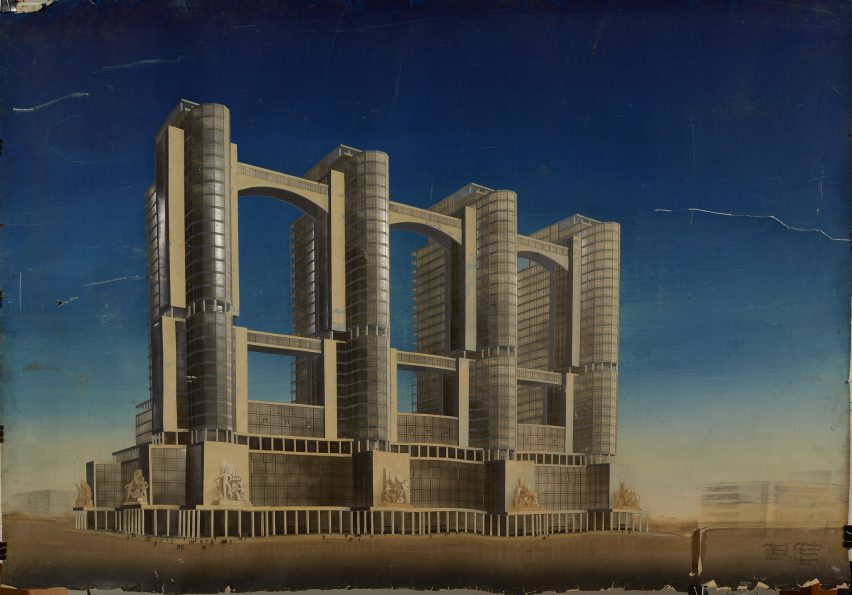

Commissariat of Heavy Industry proposals by the Vesnin brothers and Konstantin Melnikov (1934-36)

Planned for a vast 10-acre site opposite the Lenin Mausoleum on Red Square, the Commissariat of Heavy Industry could only have been built by demolishing a large chunk of Moscow's old town.

A winning design was never selected for the building, which was intended to celebrate the importance of industry to socialism, but the Design Museum showcases several proposals.

Melnikov's scheme was for a pair of 40-storey buildings linked by an escalator, while the Vesnin brothers suggested four blocks to mirror the towers of the Kremlin.

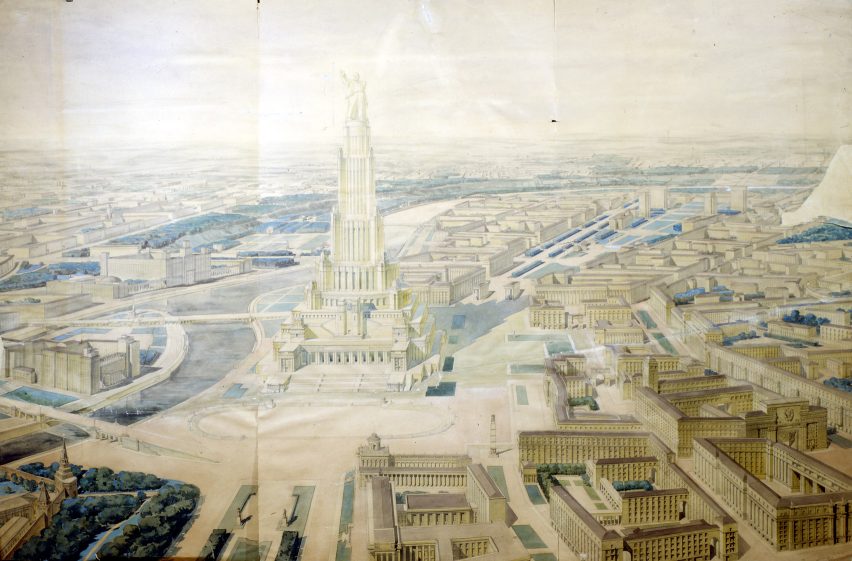

Palace of the Soviets by Boris Iofan (1931-41)

A 100-metre-tall statue of Lenin mounted on the roof of Iofan's Palace of Soviets would have taken thisbuilding to a height of 516 metres, making it the world's tallest at the time. The city's largest church – the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour – was demolished to make way for the proposal, which was allegedly selected by Josef Stalin himself.

Work began in the mid 1930s but was halted by the German invasion of 1941, and following the second world war Stalin's successor, Nikita Khrushchev, converted its foundations into an open-air swimming pool. A replica of the original cathedral now stands on the site.

Exhibition photography is by Luke Hayes.