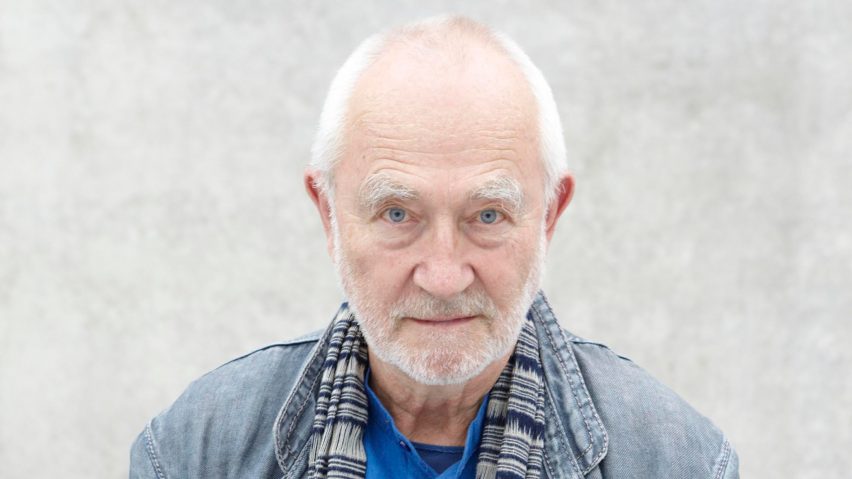

I'm trying to change my mysterious reputation, says Peter Zumthor

Swiss architect Peter Zumthor has attracted a cult following over his five-decade career, but kept a famously low profile in the media. He spoke to Dezeen about trying to dispel his mysterious reputation by taking cues from media-shy tennis star Roger Federer.

Zumthor, 74, works with a small team of around 30 based in Haldenstein, a mountain village in eastern Switzerland where his studio Atelier Peter Zumthor has been based since 1979.

The scale of his studio, its remote location and the notoriously rigorous vetting and waiting process his clients experience have contributed to his media portrayal as a "reclusive mountain-dwelling hermit".

But it's a reputation Zumthor is trying hard to rid himself of, he told Dezeen in an interview at the Fondation Beyeler in Basel, where he is working on an extension for the Renzo Piano-designed gallery.

"It's interesting that it's still lingering on. I'm doing my best to change this image," he said. "Whoever knows me says 'but you're not like people say', but that's not how the rumour goes!"

"I think 10, 15 years ago I tried to protect myself much more from influences. I was then maybe a bit harsh in my reaction," he added. "But even then it was not true. A myth. But then I was more reluctant and closed, and now I'm not."

Zumthor, who has no website, has in the past shunned phone interviews in favour of summoning journalists to his studio. They have gone on to regale readers with tales of their pilgrimages and compound the "myth" that has grown up around his practice.

When Zumthor won architecture's most illustrious award, the Pritzker Prize, in 2009, even the jury remarked on his decision to keep his practice small and secluded, but concluded that it kept his work "untouched by fad or fashion".

And in an article marking Zumthor's RIBA Gold Medal win in 2013, The Guardian's architecture critic Oliver Wainwright dubbed him "architecture's man of mystery".

"He has a mythic reputation as a reclusive mountain-dwelling hermit, a monk of materials, with standards so exacting that few clients have the patience, or deep enough pockets, to indulge his uncompromising approach," wrote Wainwright.

But Zumthor says he's now trialling a more relaxed to approach to publicity based on the unlikely role model of Swiss tennis player Roger Federer – often a reluctant but relenting interviewee.

"My children have taught me I should be much softer," said Zumthor. "My son said, 'you should be like Roger Federer, you know, if someone comes up say "yeah, take a photo", "yeah, [have a] signature" – be a nice guy, it doesn't matter, do it'."

Journalists flew in from all over Europe to do just this at a press conference unveiling his plans for three garden pavilions at the Fondation Beyeler in his hometown of Basel.

He donned a headset microphone for the occasion and took to the floor – followed by the room – to explain his hand-rendered models and drawings of the scheme. His explanations were almost inaudible over the clicking of camera lenses.

When the project completes in 2021 – a potentially improbable estimation given the lengthly timescales of Zumthor's previous projects – it will bring his number of built works to around 20.

He likens his slow and uncompromising approach to architecture to a composer creating a piece of music, or an artist working on a painting.

"I work like an artist and then I make my paintings, and I cannot delegate my paintings," said Zumthor. "To do my kind of architecture I need people to help me, I need talent, and to talk and discuss and so on but I cannot delegate the work to them."

"It's a process and this is how architects in former times, and today still, work. It's not so special. I say what what I do and I do it, this is how I work and this is what you get in my shop."

Despite his infrequent appearances in the media, Zumthor was among the top five architects on the inaugural Dezeen Hot List – meaning he was one of the most searched-for figures on the site in 2016.

The popularity of stories about his most acclaimed work, the Therme Vals spa, and the several iterations of plans for his extension to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art ensure he will make it onto the Dezeen Hot List for 2017.

Discussing these works during the interview, Zumthor said the thermal baths and hotel he designed in the Swiss hamlet of Vals had been destroyed following their sale to an "egotistical" developer.

"This project was a social project, me and my wife lived there for almost 20 years with the community and it was owned by the community and was successful," he said.

"It now belongs to a financial figure who bought all of it and destroyed it. The tragic thing is that it's an egotistical local guy that killed it all."

He also explained his decision to rework the plans for this serpentine LACMA extension, which had originally been based on the nearby La Brea tar pits, in favour of a vision that now recalls sand.

"This has to do with the fact that we had to cross a big boulevard," he said, "and so the first image was more like the black flower relating to the tar pits."

"To cross the street you cannot be organic, so the building had to change its form, have more muscle and strength. It's now more sand and earth, and before it was relating to the tar."