India is at risk of losing its architectural identity, because the country's design schools aren't teaching students to respect local heritage and traditions, according to architect Balkrishna Doshi.

The Indian architect, who turns 90 this year, said that many of the country's architects are too concerned with mimicking the aesthetics and practices of other countries, rather than learning from the legacy of their predecessors.

"It is the desire to become like somebody else," he told Dezeen, in an interview ahead of his Royal Academy annual architecture lecture this week.

This is the reason, Doshi suggested, why so many faceless skyscrapers are being built in India, and why many of the country's notable historic buildings are being demolished without concern – for instance, the experimental Hall of Nations in Delhi, built in 1972, was razed earlier this year.

"Education is at the base of all these mistakes; we are not making students conscious of the value of things," Doshi said in the interview, which took place inside the Royal Academy, in London.

"I was here this afternoon and I saw archival material. Where is the archival material in our place?" he continued. "So value is not there any more unfortunately. Because we have not made [students] conscious. It is our fault, the fault of education."

The architect founded his own design school, the Ahmedabad School of Architecture, in the 1960s. With its open-air classrooms and a focus on learning from context, the school won international recognition for its pioneering approach.

Doshi led the school, now known as CEPT University, for over 50 years. He claims it is one of the only places in India where students develop a curiosity for their environment, a curiosity that results in contextually appropriate architecture.

"I would take students into the city and ask them in their mother tongue to explain what they were thinking," he explained.

"For example, I had a class that would say: 'This is a veranda, this is a terrace, this is a balcony'. And I would say, now tell me that in your mother tongue. Then they said: 'This is the place where we sat, we chatted, we exchanged ideas'. And when they talked about windows, they said: 'This is where we look from outside in and inside out'. So a window became something of curiosity."

By contrast, he said, most architecture schools are "looking at the body of a skeleton, and not what is below the flesh".

"Certain issues are timeless, like how do you articulate space? Or how do you get the sunlight inside and work the shadows? I think that connection has been there from long back, but [other schools] have not been teaching that," he said.

"It's a question of what affects you and what triggers in you a sense of being alive. I think that's very important. [They] are not making people alive," he added.

Doshi started his own career in the office of Le Corbusier, and went on to lead the architect's projects in Chandigarh and Ahmedabad.

He became a key figure in the development of low-cost housing models in India, with projects including the Aranya Community Housing in Indore, which completed in 1989 and won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 1995.

One of the key features of Doshi's housing projects is the opportunity for adaptability – something that stems from an Indian tradition. It is commonplace for residents to add and remove extensions to their homes as the needs of families change, so the architect always tries to accommodate this.

Doshi sees this as proof that architects need to learn from their surroundings.

"I learn a great deal from nature, my teacher is nature," he said. "Do we grow up from tiny without mutilating ourselves? So why can't a building also become alive, so you can go on adding, changing, modifying?"

This ritual is so embedded in Indian culture, said Doshi, that even residents of new skyscrapers can be seen building extensions to their homes. "They're all adding to the balconies!" he exclaimed.

Dezeen was media partner for the annual architecture lecture 2017. It took place at the Royal Academy's Burlington House on 10 July 2017. We live streamed the talk and it is available to watch in full via our Facebook channel.

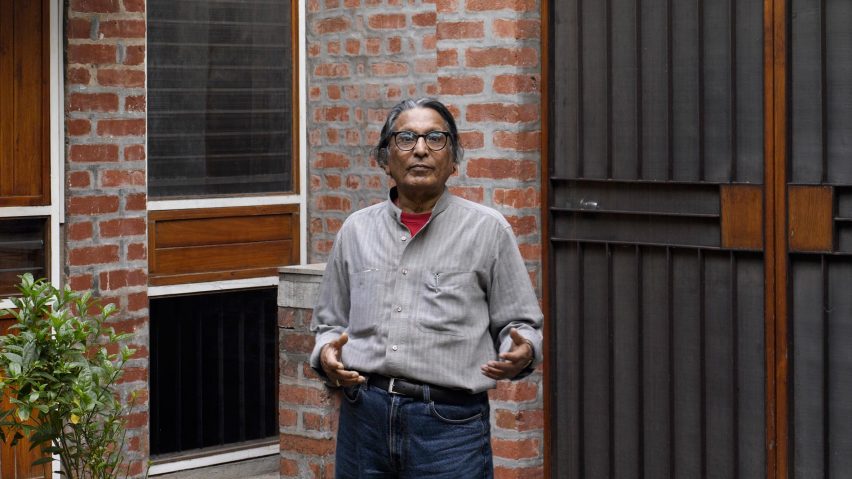

Photography is by Edmund Sumner, apart from where otherwise stated.