Japanese research group develops wearable sensor that stays on the skin for a week

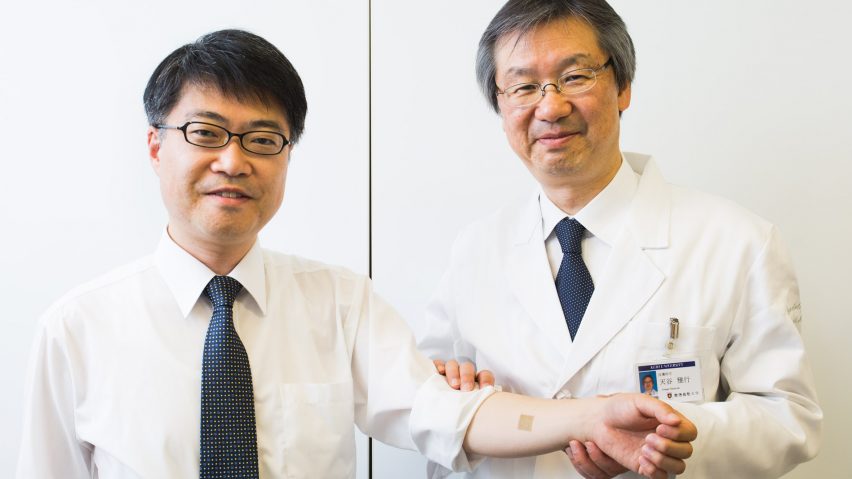

Researchers from the University of Tokyo's Graduate School of Engineering have created a temporary tattoo-style sensor that can be comfortably worn for up to a week.

The super-light and ultra-thin patch could potentially be used for continual health monitoring for both patients and athletes, offering an alternative to more invasive devices.

Designed to be hypoallergenic, the sensor can be worn for longer than similar stick-ons – such as MIT's gold-leaf temporary tattoos that can control electronics remotely.

This is because of the nanoscale mesh the electrode is made from, which includes a water-soluble polymer, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and a gold layer – chosen because it's known to be biologically compatible.

The patches are placed on the skin and sprayed with water, dissolving the PVA and allowing the wearable's gold threads to seamlessly attach to the contours, pores and ridges of human skin. Because it's breathable, it avoids the skin irritation created by other wearables with a non-dissolvable layer.

In the research group's test, subjects that wore the patches for a week suffered no inflammation, and repeated bending and stretching of the sensor proved its durability. The team also found it was as capable of reading electrical activity from muscles as the gel electrodes that are currently used.

"We learned that devices that can be worn for a week or longer for continuous monitoring were needed for practical use in medical and sports applications," said professor Takao Someya, who led the research group.

"It will become possible to monitor patients' vital signs without causing any stress or discomfort."

Wearables are a booming business, particularly as components are designed to be ever tinier, and capable of incorporating themselves directly into the user's body.

A group of scientists in California has created ultra-thin electronics than can dissolve in their environment after use, while a US tech company offered to implant microchips into all of its employees – allowing them to log into computers with the wave of a hand.