Architects reimagine Chicago's Tribune Tower with abstract skyscraper models

Fifteen alternative visions for the famous 1920s Tribune Tower competition are presented as giant models at the Chicago Architecture Biennial.

Architects, studios and teams from around the world have contributed their abstract skyscraper designs for the Vertical City exhibition at the biennial, which opened to press today.

They were asked to interpret the brief for a competition held in 1922 to design a home for the Chicago Tribune newspaper. The eventual winner, built on a prominent Michigan Avenue site at the southern end of the city's Magnificent Mile, was a neo-gothic building by New York architects John Howells and Raymond Hood.

However, the drawings of the competition's over 280 dramatically varied entries were all published and displayed in a touring exhibition that attracted international attention. The competition was also revisited in 1980, when some of the most influential architects of the time put forward their "late-entry" visions.

For the this year's biennial, artistic directors Johnston Marklee asked a selection of young studios to submit their own proposals for the historic competition, but as large-scale models rather than drawings.

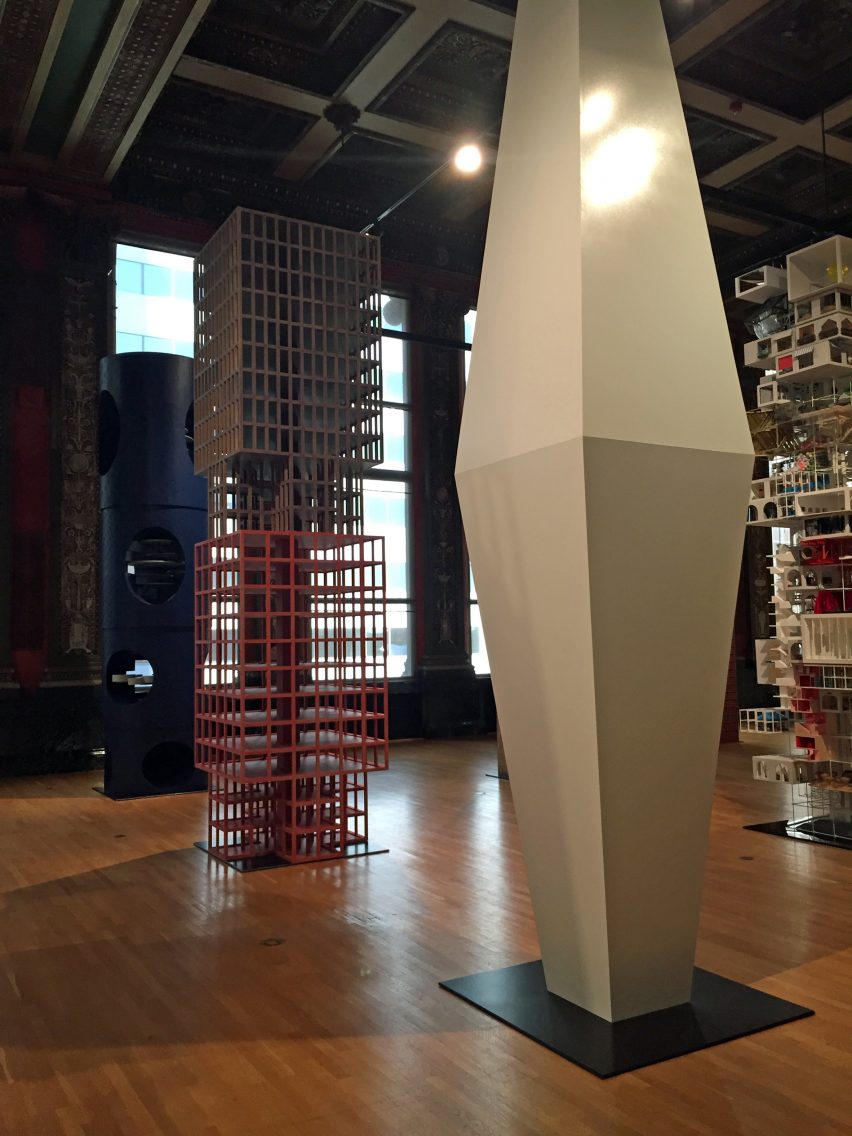

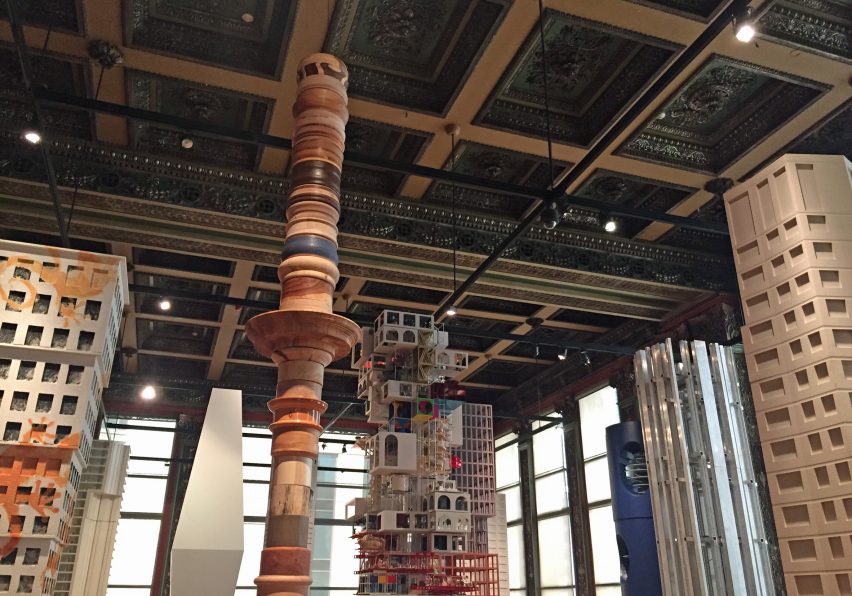

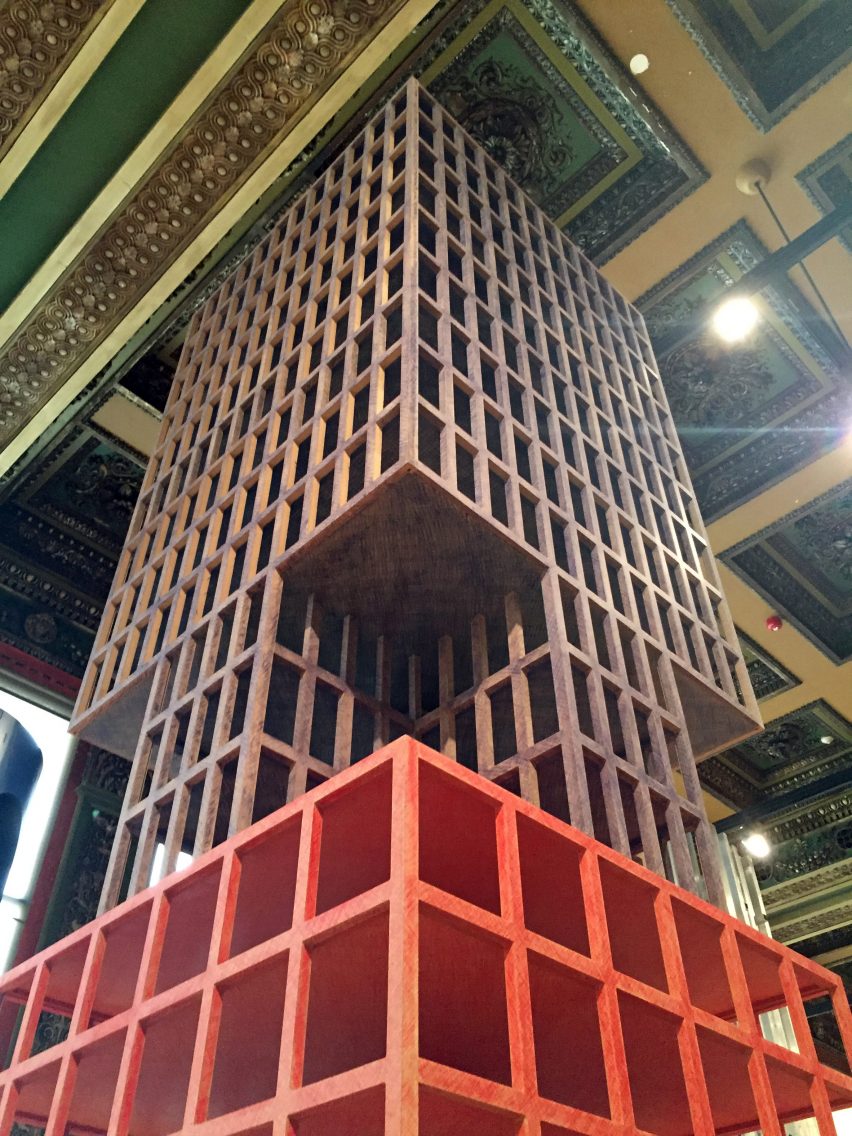

These new designs are as varied as the original entries, and are presented as 16-foot-high column-like structures in the Chicago Cultural Institute's Yates Gallery.

"We thought this was a good time to revisit the notion of the tower; the skyscraper at the size it used to be, which was much more human compared to those we see today," Johnston Marklee cofounder Mark Lee told journalists at the biennial's launch event.

"Some were thinking about structure, some were thinking about surfaces," he said. "In the end, they form this sort of hypostyle hall of towers."

Among the models is an construction of aluminium tubes by Boston- and Madrid-based Ensamble Studio, a stack of cast-glass cubes by New York practice MOS, and a totem of turned materials by London studio 6a Architects.

Sam Jacob Studio from London took elements of the completed building and merged them with Austrian architect Adolf Loos' 1922 competition entry – a building shaped like a massive doric column atop a cube-like pedestal. The result is a layered stack of different historic facades, forming a box around a central column that is visible through punctured openings.

"Our tower borrows Loos; tactic of appropriating existing architectural forms while using the Tribune's fragments as an architectural reference library, stacking each piece like an architectural game of exquisite corpse," said Jacob, who named his design Chicago Pasticcio.

Mexican architect Tatiana Bilbao similarly used an exquisite corpse approach for her (Not) Another Tower submission. Participants that included several Mexican and American studios, along with students from Columbia University's GSAPP, were each given a portion of the tower to design independently.

The elements were then assembled onto a simple white grid frame, forming a jumble of tiny rooms, structures, staircases and miscellaneous objects.

Repurposing an element from a previous project, Éric Lapierre from Paris took a decahedral column used in his firm's 365 Student Housing and rescaled it as a monolithic white tower.

Kéré Architecture – the Berlin studio behind this year's Serpentine Pavilion in London – imagines a stack of blue cylinders with cutouts inhabited by circular platforms.

Barcelona-based Barozzi/Veiga covered its dark tower with a repeated relief pattern of circles and squares, while London studio Serie Architects populated its white open-framed structure with brightly coloured miniature furniture.

A model of Loos' initial design also features in the exhibition, along with German architect Ludwig Hilberseimer's rational block from the original competition. The two bookend the new designs to provide a comparison.

The Chicago Architecture Biennial opens to the public on 16 September 2017 and runs until 7 January 2018. This second edition is themed Make New History, and asks architects to consider the past in order to shape a direction for future architectural practice, according to Johnston Marklee.

Photography is by Dezeen, unless specified otherwise. Main image is by Steve Hall.