"A war against branding is a war against people"

By making tobacco companies follow strict packaging restrictions, we're paving the way to a future where brands no longer reflect our lifestyles, argues Stephen Bayley, following the launch of his new book Signs of Life: Why Brands Matter.

The old media are dead or dying. Display advertising in newspapers will soon disappear. Maybe newspapers themselves will disappear first. Shops may soon also become things of the past, as e-commerce makes the park-and-ride, pay-and-display, out-of-town superstore look as quaint as the high street once did. Certainly, we no longer have a single producer-consumer axis, but many.

Producer-consumer axes may change, multiply, mutate, morph and evolve, but people are still motivated by desire and magic, by the promises that brands offer, the stories they tell, the secrets they share and the ambitions they excite. Your smartphone tells the time with GPS accuracy, yet you still want an Audemars Piguet, Hublot, Richard Mille, Patek Philippe or a Rolex. Don't you?

Nietzsche said all of life is a question of taste. And he was right: the choices we make define us. Our possessions define us and sometimes they betray us. Even refusing to make a choice is an irrefragable statement of intent.

A logo is a trademark that went to art college

As brands evolved into more than the sum of their tangible parts, graphic designers evolved into branding consultants, commissioned not merely to design a trademark or a poster, but to imagine and then visualise a brand.

A logo is a trademark that went to art college and postgraduate business school. For a fee of $35 a Portland State University graphics student called Carolyn Davidson created the Nike Swoosh in 1971. The athletics manufacturer was going through a transition. Previously Blue Ribbon Sports, it was decided to rename it after the Greek Goddess of Victory: Nike. The classics have often influenced the design of logos: the ancient Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company logo was inspired by the winged-foot of Hermes, messenger to the gods. Mobil used Pegasus. It's a truism that all great businesses have great logos.

Nowadays all of life is also a question of branding. Although he is not, in the strictest sense, for sale, President Trump's poorly fitting suits and terrible hair make him look like a bad argument, which, of course, he is.

So a brand is rather a complicated entity involving many of the absurdities and appetites that define existence itself. A brand is a collaboration between consumer and producer in a piece of theatre: playwright and actor working on an agreed script. But the last act is not written.

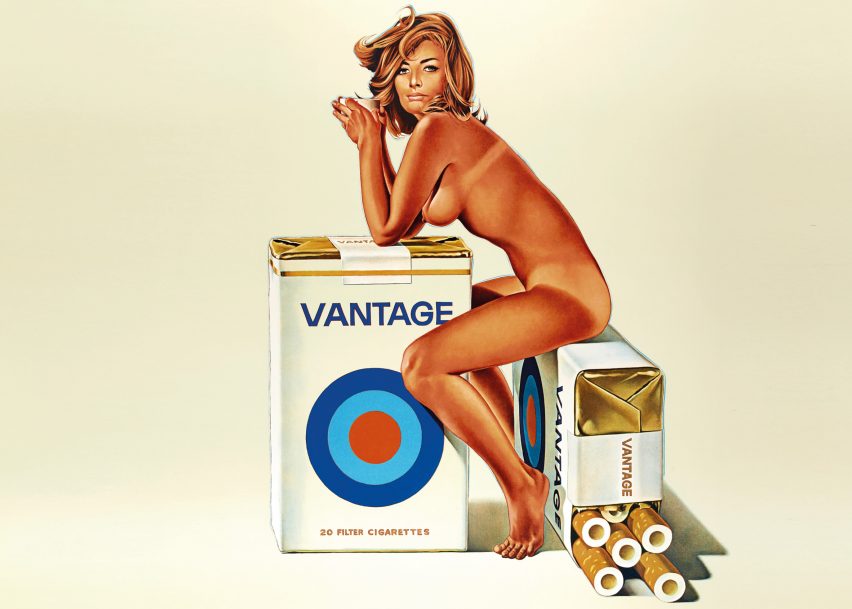

Traditional patterns of consumption and modes of communication are everywhere being tested. With the exception of Germany, billboards advertising cigarettes are now banned throughout the EU. In 2012 Australia became the first country to demand dispiriting standardised packaging for cigarettes.

Nowadays all of life is a question of branding

While consumer design has almost always involved desire and excitement, Australian authorities have now produced a brief that requires the product to be mean and off-putting: the engineering of low appeal. Market researchers determined that Pantone 448C was the ugliest colour in the swatch book and all cigarettes sold in Australia are wrapped in this dingy green-brown. When it was described as olive, the Australian federation of olive farmers made a formal complaint.

Pantone 448C – when combined with harrowing photographs of tumours or lesions, comprising by law 75 per cent of the pack's front and 90 per cent of the back, and charmless standardised typography in the style of a military latrine – efficiently removed glamour from cigarette packs. Similar generic cigarette packaging is now mandatory in the UK.

No-one wants to promote smoking, but here's a warning that this might even predict the death of branding itself. Cars and alcohol are at least as dangerous as cigarettes: why not forbid attractive presentation of them too?

The World Health Organization says one person is killed every 25 seconds in or by an automobile. Perhaps the day will come when BMWs are sold with health warnings including atrocious pictures of severed heads in autobahn accidents appearing unbidden on the car's informatics screen. When this happens, chocolate bars will be illustrated with clinical photographs of a struggling 300-pound woman being involuntarily fitted with a gastric band. Perhaps a wine label will cease to show a fine Bordelais chateau with its pleasant associations of a French country idyll and suggestions of civilised pleasure, but images of murderous drunks instead. For surely it is wrong to tempt people with pleasures that might damage them?

Generic packaging is one of the first actions in a new and sinister war against branding itself

But on the whole, banning arguments are ultimately weaker than creative ones. Montaigne, sitting alone in his Gascon tower, knew that sumptuary laws were self-defeating, since they stimulate rather than deter because humans are a perverse species. Anthony Trollope said of a 19th-century alcohol prohibition campaign: “This law must fail.” It did.

Similarly, Jazz Age America discovered banning stuff does not always create social benefit. In 1919, Andrew Volstead's law became the 18th amendment to the United States Constitution, criminalising alcohol. It created the troubled age of prohibition with its spectacular crime and lawlessness.

Still, the fear is that generic packaging is not just the last battle in the war against tobacco manufacturers, but one of the first actions in a new and more sinister war against branding itself. And a war against branding is a war against people. Brands are, quite literally, signs of life, or, at least, popular expressions of it. They are culture, art, design, value, belief. And they make a lot of money. Without them, we will in every respect be poorer.

This article is an edited extract from Signs of Life: Why Brands Matter, published by Circa Press.