"There is no need to destroy one significant cultural legacy in order to celebrate another"

The Obama Presidential Center will be presented to the Chicago City Council today. But its proposed siting in the city's Jackson Park will both remove acres of public land and blight Fredrick Law Olmsted's historic landscape design, argues The Cultural Landscape Foundation president Charles A Birnbaum.

Tod Williams and Billie Tsien are gifted architects. Their work displays a sensitivity to materiality that is often revelatory. A few of my favourite projects of theirs are the Neurosciences Institute in La Jolla (1995) and the Cranbrook Natatorium (1999).

The former is to be celebrated especially for the masterful way it responds to its site. As Tsien succinctly stated: "Our whole thought about making places is that people can enter them without destroying the clarity of space."

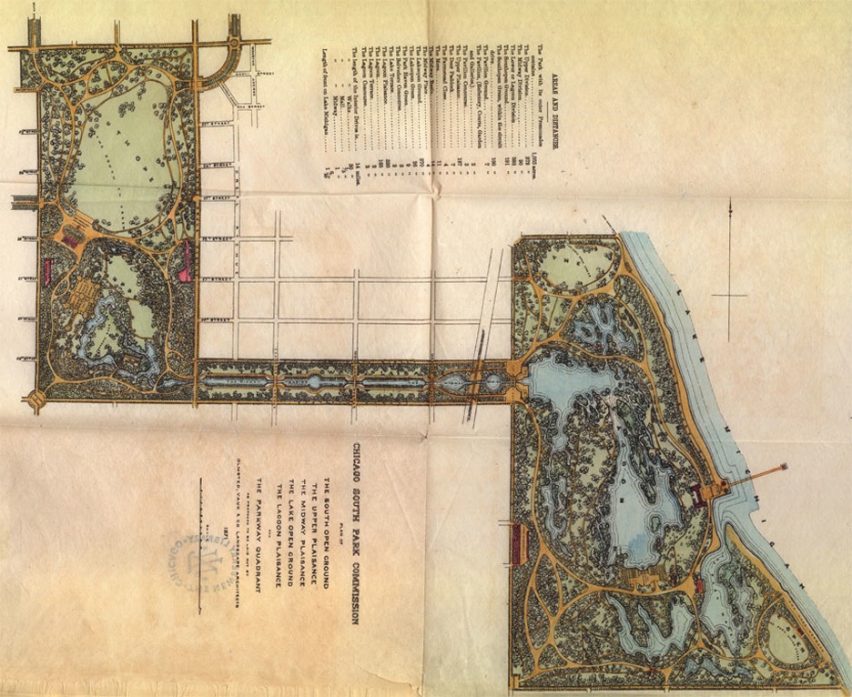

Williams and Tsien are currently mired in a controversy not entirely of their making. They are the architects of the Obama Presidential Center (OPC) in Chicago, now in the planning stages. The OPC is controversial because it is slated to be built in historic Jackson Park, which was designed in 1871 by Frederick Law Olmsted Senior, and Calvert Vaux, who also designed the world-renowned Central Park in New York City.

Jackson Park is listed in the National Register of Historic Places and, along with Washington Park and the Midway Plaisance, is part of Chicago's South Park System (the only park system designed by Olmsted and Vaux outside the State of New York). Some twenty acres of Jackson Park – parkland held in public trust for 150 years – have been confiscated to build the OPC, a privately operated enterprise.

How did that happen? It began when universities in Chicago, Honolulu, and New York competed to host what was billed as a presidential library. The University of Chicago's audacious bid called for the confiscation of public parkland on Chicago's South Side, rather than using the university's own landholdings in that area.

Some twenty acres of Jackson Park have been confiscated to build the Obama Presidential Center

Imagine if Columbia University's bid had proposed confiscating 20 acres of New York City's Central Park. It would have been called absurd (and more). But in Chicago, it was called the winning bid. For while the competing universities all touted their connection to the Obamas, Chicago offered a very special connection indeed. There, the backing of mayor Rahm Emanuel (Obama's former chief-of-staff) would ensure that the Chicago Park District, Plan Commission, City Council, and, ultimately, the State Legislature would all "get on board".

Enter Williams and Tsien, who won the prestigious OPC commission. They are now faced with the daunting prospect of adding their vision to a park designed by the "father of American landscape architecture". Notably, this won't be an entirely new experience for them. Williams and Tsien designed the Lefrak Center in Brooklyn's Prospect Park – also by Olmsted and Vaux. The park is administered by the Prospect Park Alliance, and the manager of the project was landscape architect Christian Zimmerman, who has been with the Alliance for decades.

The collaboration produced a recreation complex nestled within the 26-acre Lakeside, a $74 million (£53.6 million) restoration the Alliance calls "the largest and most ambitious project in Prospect Park since its creation over 150 years ago".

In the New Yorker, design critic Alexandra Lange noted: "The architects chose a parking lot installed during the twentieth century as their site, taking out a minimum number of trees and restoring naturalistic planning that had been overrun by asphalt." And New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman wrote: "What Mr Zimmerman, Mr Williams and Ms Tsien have collectively done is at once an act of reclamation and a reimagination of Brooklyn's pastoral heart. In essence, the project bids to turn this area back into the park's center of gravity, as Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux imagined during the 1860s."

To guide them in Chicago, Williams and Tsien have Olmsted's prolific writings about public landscapes and his ideas about Jackson Park in particular, where he worked for decades. And yet their centrepiece for the OPC is a 235-foot-tall (72-metre) tower that would dominate the park, a design intervention completely antithetical to Olmsted's intent. We know that because Olmsted said so.

The tower would be a design intervention completely antithetical to Olmsted's intent

Following the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park and a series of fires in 1894 that left the site a charred ruin, Olmsted came back with a plan to heal the park. In a letter to South Park Board president Joseph Donnersberger, he wrote that the Museum of Science and Industry – a holdover from the Exposition – was to be the only "dominating object of interest" in the park, and that "all other buildings and structures" were to "be auxiliary to and subordinate to the scenery of the park".

In Prospect Park, Williams and Tsien were careful to achieve a sensitive insertion in an already heavily altered area. But in Chicago, they will have entirely reoriented the visual and spatial experience of a landscape that still possesses a high degree of its Olmsted-era design integrity.

Moreover, the tower has gotten taller along the way, and the overall concept has morphed from a library administered by the National Archives to a "campus" (their word) comprising 7.4 acres of hardscape (buildings, plaza, and parking), with a recording studio, sports facilities, outdoor sledding paths, an auditorium, and other add-ons.

Ron Henderson, Professor and Director of the Landscape Architecture and Urbanism Program at Illinois Institute of Technology, has called the project an "urbanistic failure" that assumes if the tower is "good enough, it merits the appropriation of public land and the removal of hundreds of trees".

He adds that the accompanying "low-slung, set-back wall of buildings overlooking a parking-lot-sized plaza would better serve a high-end suburban shopping center". We seem to understand naturally the inherent shamefulness in destroying a significant work of architecture. That's something Williams and Tsien experienced first hand when New York's Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) acquired the neighbouring American Folk Museum (by Williams and Tsien), with its signature bronze facade, and tore it down.

Why is it so difficult to show understanding for a significant work of landscape architecture?

MoMA was excoriated for doing so, and the architects were heartbroken, to judge by this Tsien comment: "Emotionally, it's very painful. We don't do that many buildings, and this one is so important to us." I know those words ring true, but I wonder why is it so difficult to show the same understanding for a significant work of landscape architecture – especially one created by an undisputed master whose design intent is perfectly clear.

The Chicago Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamin's recent column was dismissive of Olmsted's design intent, questioning The Cultural Landscape Foundation for brandishing "an age-old quotation from Olmsted as though it were Holy Writ".

This prompted Williams to suggest that Olmsted's idea for the park "can be reinterpreted." Of course it can be, but I hope we will have the courage to ask whether it should be. The latest design of the OPC will soon come before the City Council and other authorities. If past is prologue, every municipal agency will acquiesce to pressure from the Obama Foundation, the University, and the mayor and will rubber stamp an approval.

Fortunately, a federal review that has recently begun could have a greater impact, and there are many organisations on a national and municipal level actively involved in it. As the CEO of one of them, I want to say clearly: I'm not against the OPC, nor am I against it being built in Chicago; and I congratulate Williams and Tsien on their commission, along with the landscape architecture firm of Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates. But there simply is no need to take public parkland, and there is no need to destroy one significant cultural legacy in order to celebrate another.

Main image of the Obama Presidential Center is by DBOX.