"There is a desire among black people to make the world over"

The powerful imagery of afrofuturism suggests what could be possible if the ambitions of black architects and designers are realised, says Ekow Eshun.

I recently started an Instagram account dedicated to afrofuturism. Even though the concept behind the term remains fairly obscure, it seemed the right time to do so.

Afrofuturism refers to work that reimagines the black experience through the fusion of science fiction, fantasy and history. Such as, for instance, retelling the story of the transatlantic slave trade as a tale of alien abduction.

The figures gathered under afrofuturism's banner are varied. They include the science-fiction novelists Samuel R Delany and Octavia Butler, pop stars Erykah Badu and Janelle Monae, the graffiti artist Rammellzee and the jazz musician Sun Ra. What unites them is a shared sensibility that looks to conjure fantastic dreams and new myths out of the everyday drama of black life.

The idea of afrofuturism was first coined by writer and critic Mark Dery in 1993 and has been avidly discussed ever since, albeit chiefly in academic circles. But that all changed in February of this year. That's when Black Panther, the Marvel movie based on the first black superhero, brought the concept dramatically closer to the mainstream.

Afrofuturism has particular relevance when it comes to questions of architecture and urbanism

There are many noteworthy aspects to the film. A dynamic cast, a captivating soundtrack by Kendrick Lamar, a sharp storyline that balances weighty consideration of white supremacy and black nationalism with moments of wit and effervescence. But the real delight is the film's depiction of Wakanda, the Black Panther's fictional African homeland.

Wakanda is a place of wonders. The country has never been invaded or colonised and, untroubled by Western interlopers, it has become the most technologically advanced nation on Earth. Wakanda's people are proud and beautiful. They worship ancient gods, drape themselves in gorgeous attire and fly hypersonic aircraft of peerless sophistication.

To bring the country to life, the film draws on visual cues from across the continent – from the thrusting cityscapes of modern metropolises like Nairobi, Johannesburg and Lagos, to costumes inspired by tribal peoples such as the Igbo of Nigeria and the Omo valley peoples of Ethiopia and South Sudan.

The vision of an ultra-developed, utopian society summoned by the make-believe Wakanda prompts an existential question that also haunts Africa in real life: what would the continent be like without the legacy of colonialism?

The Black Panther's homeland made its first appearance in Fantastic Four, issue 52, July 1966, the same comic in which the Panther himself debuted. The character's creation occurred at the height of the civil-rights struggle. It's unlikely that Panther creators Stan Lee and Jack Kirby had politics in mind when they came up with him. But the Panther is a figure of his times. Four months after July's Fantastic Four, Bobby Seale and Huey Newton formed the Black Panther party. The choice of name was unrelated to the superhero, but both perhaps were drawing from dominant cultural representations of black masculinity in that period. Similarly, the design of Wakanda reflects the way that black people in America were increasingly taking inspiration from the battles against imperialism taking place in Africa.

The make-believe Wakanda prompts an existential question that also haunts Africa in real life: what would the continent be like without the legacy of colonialism?

The country's soaring towers and glass domes are powerfully reminiscent of the extraordinary modernist structures built across Africa, as nation after nation gained independence from colonial rule – buildings such as Ghana's flying-saucer-like International Trade Fair Center or the extraordinary La Pyramide market hall in Abidjan, Ivory Coast.

Such buildings are a reminder that afrofuturism has particular relevance when it comes to questions of architecture and urbanism. From America to apartheid-era South Africa, black communities have historically been victim to policies of segregation, redlining and housing control that have forced them into closed-off, under resourced ghettos and townships. These densely populated inner city areas are typified in popular culture as terrifyingly alien worlds. The plot of Tom Wolfe's Bonfire of the Vanities, for instance, hinges on the moment its pampered hero takes a wrong turn in his Mercedes and ends up breaking down in the Bronx.

But the same inner cities have also become a fertile source of afrofuturist social commentary in movies like Neil Blomkamp's District 9 and Kibwe Tavares' dystopian short film Robots of Brixton. Similarly, Detroit techno artists such as Jeff Mills and Derrick May have famously drawn on the struggles of their post-industrial home city as source material for their music. Last year, artist and curator Ingrid LaFleur even ran for mayor of Detroit on an afrofuturist platform that called for the regeneration of the city, through technology allied to social purpose.

Afrofuturism is a subject that feels especially resonant for now. The initial inspiration for starting my Instagram account, The Afrofuturist, was to gather together some of the abundant references the Black Panther film draws on. But my scope quickly broadened. I now regard it as a way to think aloud, in public, about the themes and tropes informing black creativity around the world today, in everything from art, design and architecture to music and fashion.

Wakanda's soaring towers and glass domes are powerfully reminiscent of the extraordinary modernist structures built across Africa, as nation after nation gained independence from colonial rule

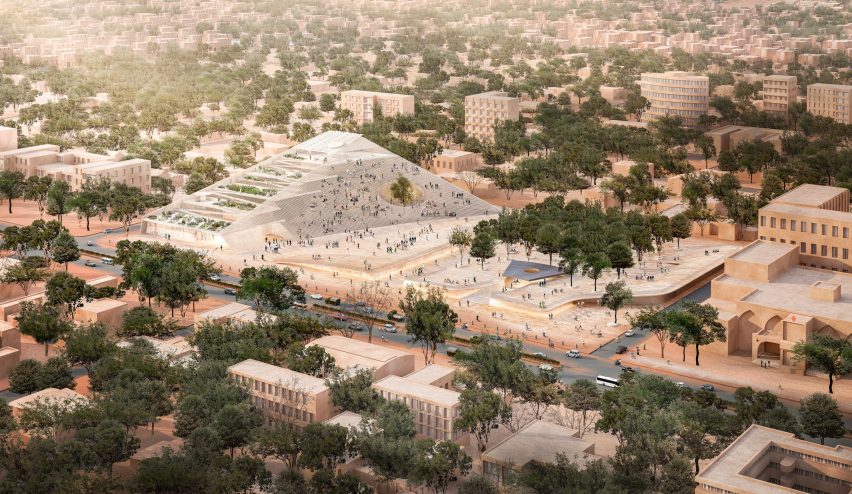

On a given day that might mean drawing imagery from the grand, stepped ziggurat that forms the centrepiece of architect Francis Kere's masterplan for a new national assembly building in Burkina Faso (pictured); or from Afronauts, Francis Bodomo's short film inspired by the true story of the 1960s Zambian space programme. It could involve pointing to the ornate, gold-leaf patterned portraiture of British-Liberian artist Lina Iris Viktor or the video for Outkast's Prototype, which features Andre 3000 as a white-robed alien touching down to Earth from an interplanetary geodesic dome.

In their own way, each of these works seems to me to have something to say about how we live now, however fantastical they seem. At its most powerful, afrofuturism intertwines the personal and the political, so that a film or a novel might be grounded in the intimate detail of ordinary life while also grappling with larger themes of race, power, gender or sexuality.

The combination of fact and fiction typical to afrofuturism offers a way to ponder complex issues of black life and identity: what does it mean to live with the collective memory of the slave trade? How does it feel to experience the microaggressions of racism every day? What's your reference point for pride or self-worth when black bodies are a locus point for fear and loathing in western culture?

In this respect, afrofuturism is about inner worlds as much as outer space. It's not a movement or a genre so much as a tendency, a shared perspective among a diverse set of artists, to position black experience at the centre not the fringes of a story.

Afrofuturism is not a movement or a genre so much as a tendency, to position black experience at the centre not the fringes of a story

One of the more commonplace, and dispiriting, experiences that many black people hold in common is being told to limit your ambitions. The comment might come from a teacher or careers adviser at school, or from a boss at work. But the message is the same – know your place.

The images I've been gathering on Instagram tell a different story. Individually and collectively, they reveal an impatience with the boundaries of the real and the prosaic, an impatience among black people at the idea that our lives should be lived at a humble, quotidian pace. Instead they reveal a desire to make the world over, to create imagery more fantastic, music more resonant, buildings more audacious, than ever previously witnessed.

As a character in a novel by Samuel R Delany, the godfather of black science fiction, once put it: "We're planning to pluck all the best stars out of the sky and stuff them in our pockets."