The buildings of Facebook, Google, and Amazon reveal a lot about how these tech giants see themselves, says Owen Hopkins.

Making sure no one interferes in elections is the most important thing Mark Zuckerberg cares about at the moment, he said as he faced the US Senate following the Cambridge Analytica data-sharing scandal. That he had to make such a statement illustrates how far Facebook has come from the project he started in his Harvard dorm-room in 2004.

In 14 years, Facebook has grown to well over 2 billion users – far larger than any single nation state. Yet as the scandal has unfolded, it has become very obvious that Zuckerberg never thought through the political and democratic implications of creating this gargantuan social network.

Even more alarming is the emerging realisation that he, and the rest of Silicon Valley, appear to have little idea what the data collection apparatus they've built are actually for, other than simply to enhance and sustain themselves. Data is a means to an end, but what is that end?

Data is a means to an end, but what is that end?

Google's famous motto "don't be evil" seemed cool when it was the rebel upstart fighting the evil empire Microsoft, but not when it has now replaced the company it sought to topple. Even if we take it at face value as an ethical statement, it tells us only what the company shouldn't do, not what it should. For the latter, we are offered the apparently utopian goal of "to organise the world's information and make it universally accessible and useful" – but how, why and with what means?

Facebook's mission, revised amid much fanfare last summer, is arguably even vaguer: "to give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together."

If we can't rely on what they say to get a clear sense of how Facebook et al see themselves and the way they are reshaping the world, then what clues do we have? The biggest and most concrete are found not in any online platform, but in their buildings.

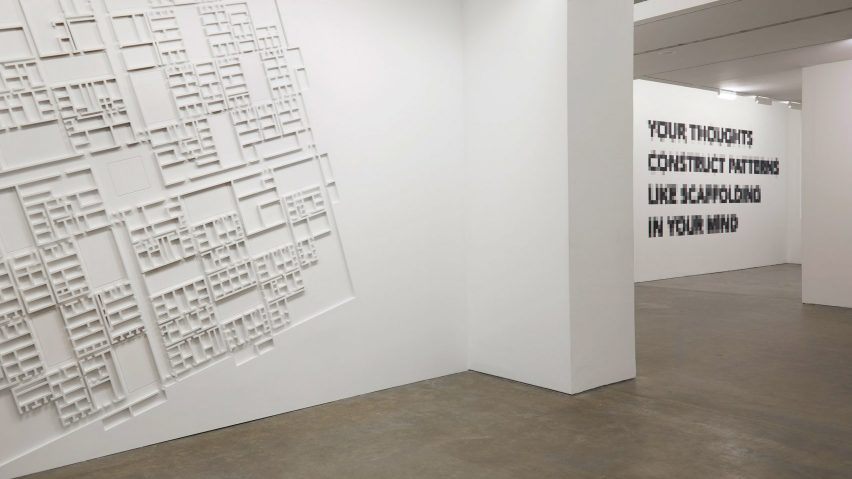

This is the contention of a timely exhibition at Ikon in Birmingham, UK by the British artists Langlands & Bell, whose practice has long been concerned with what architecture reveals about how people, societies and nations operate and see themselves. Entitled Internet Giants: Masters of the Universe, the exhibition focuses on the architectural creations – built, currently under construction, and soon to be – of Facebook, Google, Apple, and others, as well as two Chinese companies, Alibaba and Suning.

As an architectural typology, they seek to enclose, focus and concentrate, creating an interior defined against the outside world

The tech giant's vast complexes are transformed into minutely handcrafted models, which are then displayed as almost abstract structures against brightly coloured backgrounds. Stripped of open-plan work spaces, meeting pods, vast cafes, pingpong tables and the like, the buildings become icons – all eerily similar. As an architectural typology, they seek to enclose, focus and concentrate, creating an interior defined against the outside world.

Their antecedents are quite clearly not the steel and glass towers of traditional corporate HQs, but buildings like the Pentagon, GCHQ in the UK, and looking further back into history, the palace, temple and castle. One striking work transforms the plan of Google's Charleston East building into a high-relief, spanning floor to ceiling, which appears oddly reminiscent of the ruins of a great Babylonian palace.

While the architectural lineage of these buildings might be clear, they remain open to two contrasting interpretations. On the one hand, we can see them as very obvious statements of confidence, of hubris even. Spending $5 billion on a building, as Apple has just done, is a dramatic statement of its power, longevity and influence. It's the kind of money that historically only a nation-state would spend on something.

The state is just another legacy provider ripe for disruption

This is not the only way the tech giants are beginning to ape the role of the state. Most provide "public" transport for their employees, some are building their own power stations to run vast data centres, Amazon Web Services positions itself as a provider of infrastructure to businesses, and as we heard last month, Apple and Amazon are both getting into healthcare in a big way. But most critically, we see this in the challenge they pose to privacy, traditional media, national jurisdictions, the tax system and to the institutions of democracy itself. The state is just another legacy provider ripe for disruption.

The other interpretation sees these buildings as grandiose compensation for the inherent transience of the tech industry. Most of these companies do not make anything physical. Even Apple which is not interested in collecting data, but selling iPhones, does not actually make its own products.

Secondly, the brief history of the tech industry has taught us that the lifespan of most companies is very short. Of those companies around at the beginning of the tech revolution, only Apple and Microsoft are still here; the former after surviving a near death experience in the mid 1990s, and the latter now superseded in relevance.

We won't know for several decades if these buildings represent new global citadels of power

It's pretty clear the interpretation tech giants would themselves prefer. However, we won't know for several decades whether we are in the midst of a historic realignment from the era of the nation state to that of the multinational company, and if these buildings represent new global citadels of power, or will soon become like the ruined monuments of antiquity.

Every empire eventually falls and in the internet age the reigns are becoming shorter. The present backlash could be just the beginning. The question for Facebook is whether they are hoping the storm blows over and then carry on as before, or seek to fundamentally alter the terms on which they operate.

Either way, they would be advised to learn from what they seek to disrupt: nation states are not based on geography or race, but on shared culture, history and values, and the structures and institutions that perpetuate them.

It is only by re-structuring its platform to reflect a shared set of values that work to bind us together, rather than drive us apart, that Facebook is likely to survive. There's a big difference between sharing something on social media and the shared values that connect us as individuals and a society.

Exhibition photograph is by Stuart Whipps.