Architects can make a big impact "at a very small scale" say Grafton Architects founders

Architects can't solve the world's problems, but they can still make a significant impact, say Venice Architecture Biennale directors Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara, who compare architecture to the slow-food movement.

The duo, who are the founders of Dublin-based studio Grafton Architects, claim that architects don't have the power to combat global issues. But they say that small projects can still make a huge contribution to society, and they urge architects to be optimistic about the importance of their work.

"It's like the slow-food movement – you can sometimes operate at a very small scale and have an impact," said McNamara.

"There's no reason to feel depressed by not being able to solve the big problems of the world," she said. "Because architects don't have power. We only have power to make architecture. But we believe that this can make small changes, and we know that a lot of small changes can lead to something big and build up a momentum."

Grafton's manifesto calls for "generosity of spirit" in architecture

McNamara said that even they are sometimes frustrated by not being able to design "at the scale of infrastructure", but that they don't let it get to them.

"If you don't have that, you're still in the big picture," she said.

The pair are the 16th curators of the Venice Architecture Biennale, which opens to the public this week. They chose the theme Freespace and have compiled a manifesto outlining the principles of the concept.

The manifesto calls for "generosity of spirit and a sense of humanity at the core of architecture's agenda", and "the opportunity to emphasise nature's free gifts of light, air, gravity, materials".

"Architecture is an optimistic discipline"

Farrell and McNamara told Dezeen that Freespace refers to the gifts that architects give for free, through good design.

"Architecture is not building," said Farrell. "It's about finding the ingredients that lift something over the threshold, from being something that is okay to being something of value."

They cite two of the university buildings they've designed – in Lima, Peru, and in Milan, Italy – as examples of buildings that include gifts, whether by "trapping" the beauty of nature, or by creating a public space where people meet and interact.

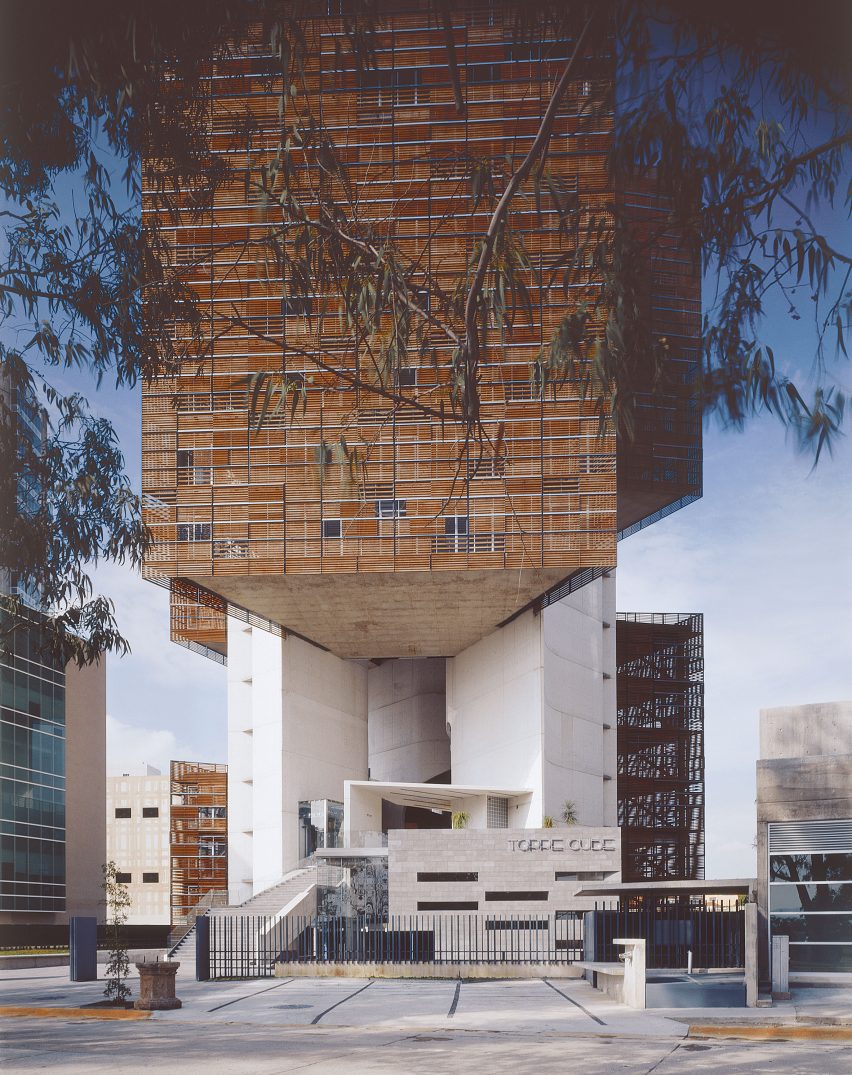

Each exhibit in the biennale was selected for the same reason. Examples include a series of historic chapels in Sweden, which provide generous canopies at their entrances, an office tower designed by Spanish architect Carme Pinós with a plaza in its base, and a pavilion built using "green steel" bamboo by Vietnamese studio Vo Trong Nghia Architects.

"We fundamentally believe architecture is an optimistic discipline," added Farrell.

"I would love for people to realise that a curved brick, or a beautiful bridge, or a cherry blossom… all of these things contribute to a sense of beauty in the world," she said. "We are 'tsunamied' by the sadness and terror and difficulties of life, but life is also beautiful and we need to balance that."

The Venice Architecture Biennale opens to the public on 26 May 2018 and continues until 25 November.

Read on for for the full interview with Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara:

Amy Frearson: Can you explain the theme Freespace and why you chose it?

Shelley McNamara: We wanted the term space to be in the title, because we believe that architects are space-makers, not just object-makers. And the idea of Freespace was something that was in the air in our office – it's the extra component that we make in a project, the thing that hasn't been requested. It's the capacity in our work to give something back to the places that we're inhabiting.

When you're asked to do the biennale, it starts very quickly. So we looked at this wish we have in our own work, to find something this is beyond programme. Sometimes it is physical space and sometimes it isn't. But once it becomes part of our agenda, it somehow drives the design in a very particular way.

The meaning of the word Freespace could also be do with time and memory: the free space of history, the free space of time. Time is very alive in architecture and its not linear, it's now, whether it's the present, the past or the future.

It's also to do with free thinking. Imagination is one of the most powerful tools that we have as architects. We have to imagine worlds that don't yet exist.

Yvonne Farrell: We didn't want our exhibition to be object-driven. With our manifesto, the issue of space was the first thing we thought of – it was really about the containment rather than the container. And free space is not so much like a parking space, it is something that is gifted.

As architects, we navigate between a commissioned building and an art form. There is this kind of seam. We have to resist capitulating into commercialism, but also the void of isolated art. We weave a line between a certain kind of reality and a certain kind of dream. It's an amazing discipline.

And our manifesto is like a value system you can measure a project against. Is the earth your client? Does the project have an element of generosity? How do you see the moon?

The final point on the manifesto is key. It is about the idea of a society that plants trees under whose shadow they will never sit. You have to remember that something you do now has repercussions. Architecture, if it lasts, has implications over time.

Amy Frearson: Earlier you summarised the idea of Freespace as "the gifts that architects give". Can you give me some examples from your own architectural projects?

Yvonne Farrell: In Lima, in Peru, when we were doing the competition [for the Universidad de Ingeniería y Tecnología], our question was: what is this place? What is unique about it? It is 12 degrees from the equator and has a unique climate, and we thought, if it's unique then we should be able to respond in a unique way.

So there, the free gifts came from nature. It was the breeze coming in from the ocean, that could sustain a temperate climate within the university and the generosity of the place. We wanted to give that new university our interpretation of the physics of culture. We were strangers from another part of the earth, but we invented something that we hoped represented their particular place. Our interpretation was our gift: a vertical university.

We hope students lean out and look over Lima, look at the Andes, look at the ocean and know where they are.

Shelley McNamara: In Milan, at the Bocconi university, the city flows through the university. During the day, it is a filter and it connects with the city – that's something we love, the space between. It's those space between the functions, the uses, that liberate that project.

There are also two projects we're doing in London at the moment. One is for Kingston University, where we're making a colonnade on three sides. One side is a bus stop, so that when people are waiting they can use the colonnade. That's a free space.

The other is the London School of Economics, where we have compressed the programme to release space on the ground floor that is unprogrammed. Anybody can walk through that space and enjoy it, because it's like a little indoor piazza.

And in some of the schools we've done, we've made covered outdoor space, or a long seat in the sun that we see people fighting for.

So it's always there, and more so as we get older.

Amy Frearson: I was expecting the exhibition to be full of ideas for how architects can introduce more free space into buildings and places. But actually, it's more of a celebration of free space that already exists, even in something as mundane as a doorway threshold. Was that your intention?

Yvonne Farrell: We wanted to describe the spectrum. At one end, we have Assemble's beautiful tiles from Liverpool, which were crafted to make a surface in a mirrored room, or Flores & Prats making a project out of a beam of sunlight.

And at the other, we have BIG working to keep the water out of Manhattan, or Frederick Law Olmsted, civilising parts of Buffalo in the United States.

It's that range. The intangible is not actually intangible. What we're saying is that architects around the world are focusing to try and find something of beauty to trap. Architecture is not building. It's about finding the ingredients that lift something over the threshold, from being something that is okay to being something of value. Architecture is a real thing that sustains you and lifts your spirit.

When you're in the Giardini, in the Central Pavilion, we want you to realise that these are roof-lit building rooms, and when you're in the Arsenale, that you realise this is a building with its own character. We're trying to peel away the beauty of things, sunlight, moonlight, repeated structure. A human being is a physical entity and architecture is a physical response to space. We're trying to heighten things that are successful, to show them to you again, and to remind you how lovely they are.

Amy Frearson: Two years ago, Alejandro Aravena used the biennale to show how architects need to provide solutions to the big problems of the world. Are you saying we should put the big issues to one side and focus more on the joy of the everyday?

Shelley McNamara: We don't think we are pushing the big issues to one side. It's like the slow-food movement – you can sometimes operate at a very small scale and have an impact.

There's no reason to feel depressed by not being able to solve the big problems of the world. Because architects don't have power. We only have power to make architecture. But we believe that this can make small changes, and we know that a lot of small changes can lead to something big and build up a momentum. To make relevant small work, I think you have to be aware of the big issues.

If you think of Gion Caminada, working in the tiny village of Vrin, he is acutely aware of the big issues but is working at a small scale. You can have radical interventions happening at a small scale as well as a big scale. Many architects are frustrated, including us, at not having the ability to work at the scale of infrastructure, on roads and bridges, or strategies for cities. But if you don't have that, you're still in the big picture.

Yvonne Farrell: Also, somebody like Anna Heringer, she takes a shirt and uses it to show how we are implicit in the unravelling of villages in Bangladesh. Workers have to leave their small villages to go to the main cities to work.

They can't find accommodation, they have to leave their families behind, and its hard to have kids when they are working. What Heringer is saying, embroidered on the cloth, is that the fabric of society is very strongly interwoven and we're all complicit in its unravelling.

What we're saying is, we want you to think of the earth as your client. We want you to think that every time you use Carrara marble, you are carving into a mountain.

As architects, everything we specify… we are cutting trees, we are using sand, it's part of what we do. But we also make reality, and that reality can be a joyous thing. We fundamentally believe architecture is an optimistic discipline.

Amy Frearson: What is the overall message you would like visitors to take away from the exhibition?

Shelley McNamara: I would love if people are brought closer to architecture and have a desire to be part of the making of architecture, whether through making, commissioning or awareness. We think that growing the desire for architecture is key to the flourishing of architecture.

Yvonne Farrell: I would love for people to realise that a curved brick or a beautiful bridge or a cherry blossom… all of these things contribute to a sense of beauty in the world. We are 'tsunamied' by the sadness and terror and difficulties of life, but life is also beautiful and we need to balance that.