When New York lighting studio Apparatus held a party themed around Tehran in the 1970s, guests turned up as camel salesmen and belly dancers. Designers should know better than to resort to such lazy cultural stereotypes, says Sina Sohrab.

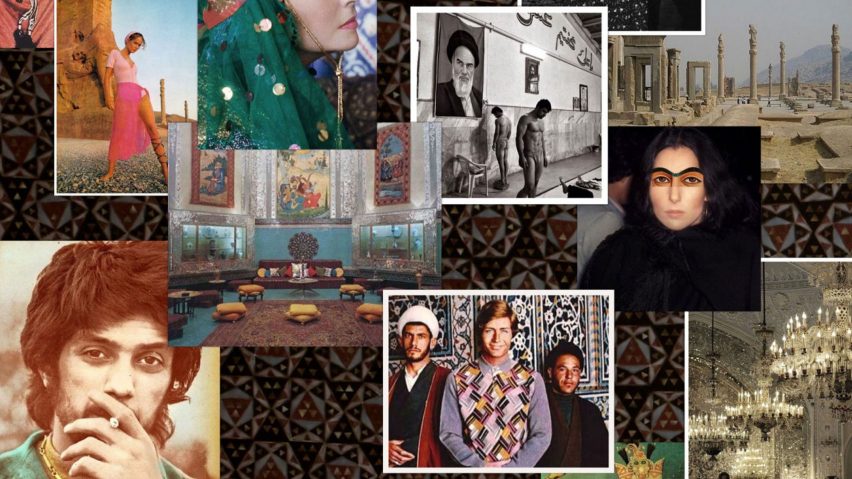

In the midst of New York design week, I attended a party hosted by the lighting design studio Apparatus. Admittedly, I don't know the founders Jeremy Anderson or Gabriel Hendifar; I've met Gabriel once and just recently learned that he, like myself, is also Iranian. The premise for the party – dubbed Club Pars – was "1970s Tehran" [shown in the mood board released with the invitation, main image]. So, as one of the few Iranians in the design world, I was intrigued by the idea.

It was clear from the food – a mix of authentic Persian stews, rice and kebobs – and the music – early Googoosh and Leila Forouhar – that the event was informed, contextual and well intentioned. And then the guests arrived, and with them, their choice to interpret the theme as license to dress as Middle Eastern caricatures; donning turbans, robes, bejewelled veils, headdresses and even a few thawbs.

It is with honest reluctance that I choose to publicly decipher why this has an effect on me, as both an Iranian, and as a member of the design community. Such is the power of open displays of racially coded ignorance: the experience has stayed in my mind, causing me to doubt my own connection to my Iranian-ness, and my agency in expressing my discomfort.

The need to explain why something is racially insensitive merely highlights a cognitive bias of which, as a minority, I do not have the luxury. But, in replaying the night throughout the last few weeks it became clear that, as a designer, it is a critical responsibility of our profession to push for this discourse.

The event was informed, contextual and well intentioned. And then the guests arrived...

I insist then that we engage our mistakes – it is, after all, one of the most valuable aspects of the design process. In our work, we design with genuine curiosity, deep research, and with an attention to specificity.

At a minimum, we should treat other cultures with this same attention – not as a shared open-use device, but as a specific set of distinguishing attributes that originate from and are enmeshed with real people, interesting and valid because they are distinct. It must be adopted with the same investment, care and understanding for its originators.

The idea of Club Pars, of an Iranian-themed party, is not in itself a problem. When performed with an informed and respectful perspective, costume becomes homage – the important distinguishing factors, in many cases, between celebration and degradation. When done carelessly – dashed-off, uninformed, or through wilful ignorance – it is merely the use of stereotype for personal gain.

This is particularly salient in the context of the design world: where the lines between homage and exploitative appropriation are often blurred; where our work – and through it, our cultures – permeate an increasingly global market, leading us further and further into grey areas.

In the design world, the lines between homage and exploitative appropriation are often blurred

What I saw last month, however, did not live in that grey space. It was a particularly perplexing display due to its occurrence within a celebration of our community – one of professionals that purport themselves to be rigorous, intellectual, and open-minded; those that have the awareness and the means to know better.

The greatest irony is that pre-revolution Tehran in the 1970s was a virtual mirror of America of the same era: the women wore mini-skirts, the men wore polyester suits, and chest hair was everywhere. Given this, it was wild to see so many familiar faces in such dissonant attire.

Some guests appeared to be camel salesmen or belly dancers, the very stereotypes that have been used to in-dignify the Middle East for years, with very little regard for which of the many diverse cultures in the region they were taking from.

Tehran in 1970s was nothing like a Bedouin-and-camel-trodden desert – an easy high- (or low-) way to summarise a culture with deep roots in poetry, art, tolerance, and love, despite what has been shown of it in recent years. Seventies Tehran was Keyvan Khosrovani's Tehran, where traditional Iranian aesthetics and modern design ideas were molten into Boutique Number One – where Qashqai patterns and modern attire blended a world of Persian ornament, from gardens to carpets, and modern life.

As Iranians, misrepresentations of our culture have been increasingly used to isolate and dehumanise us

It was also Iran-America Society poetry nights' Tehran, where William Stafford could recite his poetry to Iranian students; and Museum of Contemporary Art's Tehran, where some of the yet to be seen again works by Warhol and Picasso were hanging; and yes, Dr Shariati's Tehran (a Sorbonne graduate with new interpretations of Islam) where the dialogue between the modern and orthodoxy in religious thought was flowing.

As Iranians, elements of our culture, as well as misrepresentations of it, have been increasingly used to isolate and dehumanise us, as evidence of our being "other-than": whether other-than-civilised or other-than-Western, and thereby as a justification for exclusion.

Consequently, the turbans one wears to a party as costume, to look good and have a fun time, are the same ones that often get torn off the heads of Muslims and Sikhs in public, that get them detained at airports, or surveilled in their schools. You can wear them without consequence or worry, but many cannot, and – in the context of Iran, or 1970s Tehran – never did. It misrepresents an older-than-Islam culture that is already at odds with the symbols of some of its pillagers.

My parents stayed in Iran through the revolution and watched the country change. I was born there, and we left in the late 1990s because the American brand of freedom had a shine to it. As with all shiny things, this too has tarnished in recent years, as the reality of race relations has finally taken the spotlight. This is why, especially now, it is important to be mindful of how we use one another's cultures, or distinguishing characteristics, for our own entertainment.