Centimetre-sized soft robots could one day be used to perform surgery and enter other tight spaces, using a method devised by researchers at Harvard University.

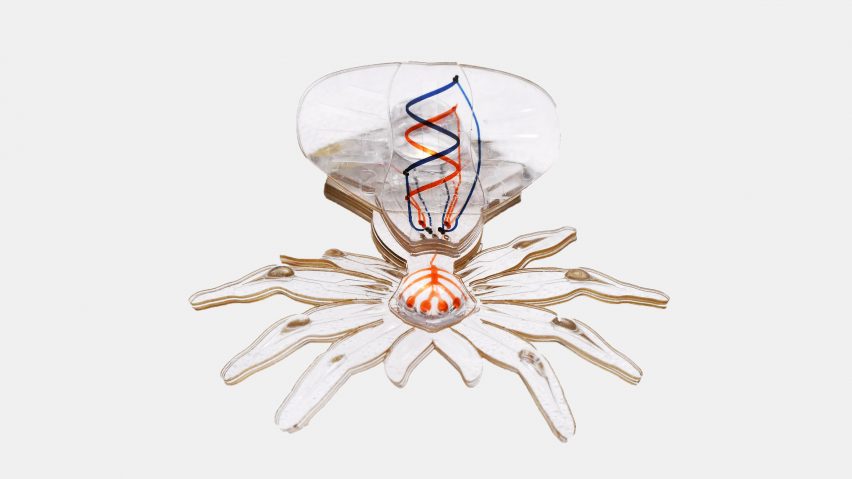

The researchers made a tiny eight-legged robot — whose form is inspired by the colourful Australian peacock spider — to demonstrate their new soft material micro-fabrication process.

The process involves bonding together layers of silicone rubber to make the body of the robot, and injecting phase-changing material into it to control its movements.

They dub the process microfluidic origami for reconfigurable pneumatic/hydraulic devices (or MORPH), and it enables them to work on a much smaller scale than has previously been possible in soft robotics.

"The MORPH approach could open up the field of soft robotics to researchers who are more focused on medical applications where the smaller sizes and flexibility of these robots could enable an entirely new approach to endoscopy and microsurgery," said bioengineer Donald Ingber, the founding director of Harvard University's Wyss Institute.

Researchers at the institute carried out the work in cooperation with the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and Boston University.

"In the realm of soft robotic devices, this new fabrication approach can pave the way towards achieving similar levels of complexity and functionality on this small scale as those exhibited by their rigid counterparts," added Robert Wood, one of the project leads.

In addition to surgery, the researchers imagine the technology being used for wearable devices and wherever micro-scale manipulation is required.

The MORPH process combines a number of already existing techniques together. In the case of the spider-inspired device, the team laser-cut 12 layers of elastic silicone and then joined them together to create the transparent octopedal body, which photos show is roughly the size of a US one-penny coin.

The silicone layers have a network of carefully calculated grooves printed into them. The injection of phase-changing materials like UV-curable resin into these grooves allows the engineers to control how it moves.

Exposure to UV light causes the resin to harden, triggering the device to self-fold into the desired shape — hence the "microfluidic origami" in the MORPH name.

The spider's swollen abdomen and curved legs were both created by this process.

"The smallest soft robotic systems still tend to be very simple, with usually only one degree of freedom, which means that they can only actuate one particular change in shape or type of movement," said Sheila Russo, another key researcher on the project.

"By developing a new hybrid technology that merges three different fabrication techniques, we created a soft robotic spider made only of silicone rubber with 18 degrees of freedom, encompassing changes in structure, motion, and colour, and with tiny features in the micrometre range."

The researchers published their findings in the journal Advanced Materials last week.

Research into soft robotics is generating a lot of interest, because the pliable devices have the ability to perform tasks that rigid machines can't manage.

Recent advances have seen a robot fish that can swim deep underwater to capture close-up footage and a robot that can change the texture of its skin to communicate how its feeling.

Photography is by Wyss Institute at Harvard University.