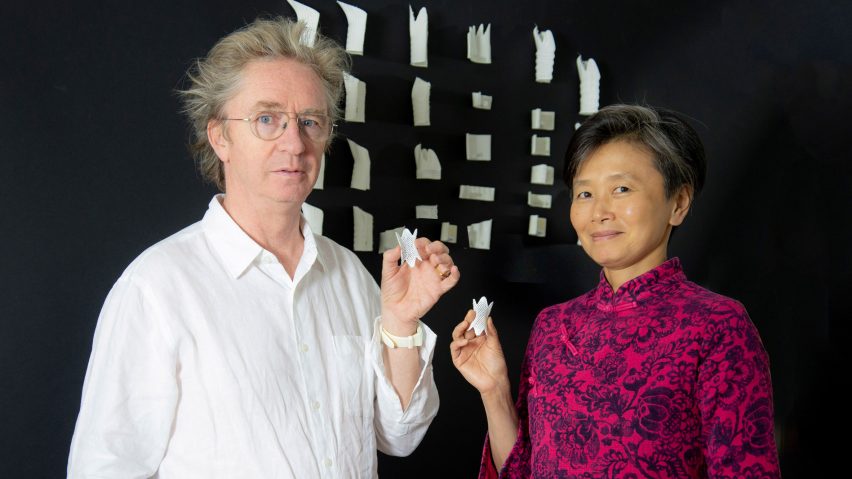

Architects Mike Tonkin and Anna Liu have created a prototype stent that adapts to a patient's throat for use after tracheal transplant surgery.

Tonkin and Liu, founders of London-based architecture studio Tonkin Liu, adapted the design of their single surface structural technology – called the shell lace structure – to create the stent.

Unlike the tubular mesh stents commonly used after surgery on the windpipe, their version is C-shaped and fits to the individual shape of each person's throat.

The prototype has been manufactured from medical grade silicone with a perforated surface that allows the wound to breath, and makes drug delivery to the tissues possible, which together prevent infection.

To insert the stent, doctors must turn the item inside out and place it inside the windpipe cavity. It then unfurls and sits firmly within the patient's body due to the natural external pressure, without danger of slippage.

The prototype is "a remarkable and unprecedented stent invention, that is ground-breaking in the context of currently available devices," said Martin Birchall, UCL professor of laryngology.

Tonkin and Liu created the architectural shell lace structure, following a decade of research, as a sheet material that would perform as efficiently as items in the natural world.

The sheets were designed through abstracting design principles from the physiological makeup of molluscs and plants, in collaboration with scientists from the Natural History Museum.

Previously Tonkin Liu had only used the structure for architectural purposes, such as ultra-lightweight pavilions, bridges and towers.

Alerted to an unmet medical need by a clinical researcher at a talk they took part in 2014, the architects set about making prototypes of possible stents using the structure as their starting point.

They worked with engineers Arup to develop the concept, and secured funding for a year long research and development project from Innovate UK, the British government's innovation fund.

The architectural version of the shell lace structure has now been adapted and recreated 500 times smaller for the medical device.

To design the prototype Tonkin Liu digitally scanned a pig's trachea, as the animal's throat is similar to that of a human, to create a 3D-printed model that was five times larger than life size. The architects tested this as they would an architectural model in the studio.

"To us it was no different to observing the particular characterises of a site. What were its peculiarities, the demands and the opportunities?" Liu told Dezeen.

They found that the trachea consists of a series of C-shaped rings, connected by softer tissues, which move up and down, with flexible tissue spanning the gap in the C. Using these findings, they developed models on which to develop and test the prototype stents.

"We mimicked these characteristic through a series of simple and intuitive rubber band models, which would later prove to be key to our invention," said Liu.

The stent is currently patent-pending and the architects hope that it will be rolled out for use in trachea transplant surgery: "Our aim is now to bring the Shell Lace Stent to manufacture stage and see it bring tangible benefits to patients globally," said Tonkin.

Liu points out that architects are very adept at working with cutting-edge digital design and fabrication tools, so have much to offer the medical profession in creating better medical devices.

"The advancement of these tools in the past five to 10 years have meant that bespoke and complex form can be made more responsively and affordable," she said.

"This suits the tools' application to designing a much more bespoke, formally complex, fit-for-purpose device for different parts of the human body."

As well as designing for medical professional use, designers have often intervened to make medical centres for inviting, such as Morag Mysercough's colourful re-design of the wards at Sheffield Children's Hospital, and this painted cancer care centre in Copenhagen.