The Bauhaus fundamentally changed the philosophy and methodology of design education in the United States, says Margret Kentgens-Craig, author of The Bauhaus and America, in this Opinion as part of our Bauhaus 100 series.

The dramatic circumstances of the Bauhaus closing and the aftermath made it a political metaphor. If the National Socialists had intended the death of the Bauhaus, ironically the break of the institution led to the continuity of the idea: with the emigration of faculty the Bauhaus agenda spread worldwide. Nowhere did its artistic and intellectual heritage find ground as fertile as in America.

Not surprisingly, in foreign context the novelty and complexity of the Bauhaus became subject to a fragmented reception, often limited to expert circles and centers of intellectual exchange.

In 1930, the first US exhibition of the Bauhaus, and the only one during the school's existence, took place at Harvard. The organisers, students Lincoln Kirstein, Edward MM Warburg, and John Walker III, presented paintings, drawings, prints, and decorative arts by current and past Bauhaus artists, including Herbert Bayer, Lyonel Feininger, Johannes Itten, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Oskar Schlemmer, and Lothar Schreyer.

The show traveled to New York and Chicago, where its effect on public awareness of the Bauhaus was considered most significant. On the West Coast, Bauhaus and other European avant-garde painters were introduced as well, through Galka Scheyer's Blue Four exhibitions.

The attention moved from the visual arts to architecture when in 1932 Barr and Johnson along with Henry-Russell Hitchcock staged the famous "International Style" exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, accompanied by a catalogue and book.

This powerful mix of agents presented two of the famous architect-directors of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe, with works that in the future would obtain iconic status. In 1937, Gropius was appointed to Harvard's GSD and brought along his former student Marcel Breuer. In 1938, Mies van der Rohe was called to head the architecture school at the Armour Institute in Chicago (later IIT) and began building his distinguished American career.

Critics argued that the modernism of the Bauhaus did not grow from the social and historical context of the United States

The focus on architecture merged with a Gropius-centric perception when in the same year the life-long patron saint of the Bauhaus – his wife Ise – and former colleague Herbert Bayer curated a Bauhaus exhibition at the MoMA, which for decades would dominate the image of the Bauhaus.

The show was limited to Gropius' term and did not include the work under Hannes Meyer and Mies van der Rohe, appointed directors of the Bauhaus in 1928 and 1930, respectively. While putting the Bauhaus on a larger map of public awareness, the exhibition added to an already loop-sided understanding. By the end of their careers, Mies and Gropius were both honoured with honorary doctorates and the prestigious AIA Gold Medal.

The Bauhaus' popularity in America, however, was always countered by skepticism and harsh criticism. The effect showed even in popular culture when in 1981, Tom Wolfe's misinformed book From Bauhaus to Our House hit the shelves.

Architecture was the main battleground. It was a battle not only fought over style and technology but over the signature of American identity as well. Critics argued that the modernism of the Bauhaus did not grow from the social and historical context of the United States but was instead imported and alien.

This assertion is only true if the criteria applied to the matter are completely generalised. However, it is indisputable that the different and diverse American contexts did favour Bauhaus ideas to take hold. Furthermore, preconditions and standards of judgment change in the course of time. The Bauhaus cannot be understood without contextualising.

At its centenary, the Bauhaus remains relevant. While the institution is now history its ideas were highly active in transforming the American theory, pedagogy, and practice of art, design, and architecture. Even on a merely formal level the aesthetic quality of Bauhaus products resonates with today's audiences.

There is a broader and deeper impact that remains alive. This is the pedagogy of the so-called Bauhaus Vorkurs – often considered the soul of Bauhaus education

Reproductions of 1920s Bauhaus products such as Josef Albers' fruit bowl, the Jucker-Wagenfeld table lamp, Marcel Breuer's and Mies van der Rohe's chairs and tables, Marianne Brandt's tea kettle and ash tray stand side-by-side with young design inventions in museum and design stores, from New York to San Francisco.

A more striking example however, is the infusion of Bauhaus genes into the company that we have come to know as America's most valuable. Steve Jobs, a confessed and well-informed disciple of the Bauhaus, conceived and developed Apple as a design rather than technology company, relying on Bauhaus-inspired designers Hartmut Esslinger and Jonathan Ive.

There is however a broader and deeper impact that remains alive. This is the pedagogy of the so-called Bauhaus Vorkurs, or preliminary course – often considered the soul of Bauhaus education. It became transplanted to American schools where, dubbed as Elementary or Foundation Course or simply Basic Design it was transformed according to new conditions.

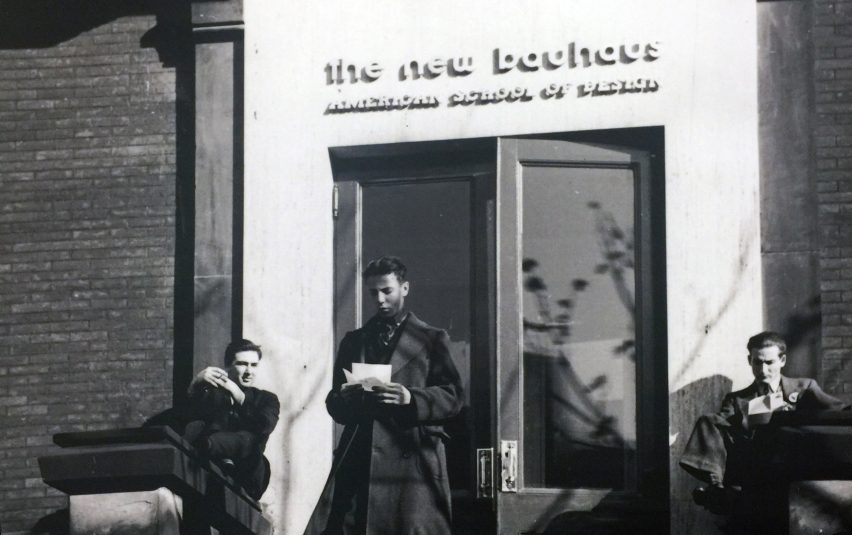

It came to Chicago where in 1937 the New Bauhaus established a program in art, design and architecture that became as authentic as possible in the New World. Here László Moholy-Nagy contributed the elementary program and the artistic substance of his life work.

The New Bauhaus, nowadays as the Institute of Design of the Illinois Institute of Technology, continues its influence into the present and is the largest full-time graduate-only design program in the US. In the early 2000s, the Institute helped launch the design thinking movement, thus connecting design closer to business innovation.

In the United States it was mainly Albers' version of the Bauhaus education that left its impression

The Vorkurs incorporated the Bauhaus' humanistic ideological roots. It was initially conceived in Weimar by Swiss artist Johannes Itten, later continued there by László Moholy-Nagy and eventually assigned to Josef Albers. In the United States it was mainly Albers' version that left its impression. In 1933 already, he came to Black Mountain College in North Carolina, along with his wife Anni, a textile artist.

Albers was one of the most versatile protagonists at the Bauhaus. He experienced the Bauhaus throughout its stages, as student, teacher, and deputy director. His work ranged from drawing, painting and glass works to photography and lettering, product and architectural design, from colour theory and experimentation to poetry. Albers' pedagogical and artistic interests are highly intertwined.

The central theme in Albers' pedagogy were the limitation and relativity of visual perception. "Nur der Schein trügt nicht," (only the appearance does not betray) was the conclusion of his experiments into the limitations of the human eye and subsequent assessment.

Subsequently his mantra became "I want to open eyes" meaning to train students to see more sharply and objectively in order to differentiate between fact and deception. This goal still holds currency in today's world of visual overkill and often superficial, non-selective processing of information.

Sensitising perception, in particular visual perception, is related to the training of critical thinking and analysis, problem solving and decision making - noticing gray zones in an often black and white painted global environment. Understanding and responding in constructive ways is as crucial now as it was in 1919 and 1933.

Although the Bauhaus as a whole could not be transplanted, specific programs, structures, and courses could

Albers believed art to be a vehicle in the "adjustment of the individual as a whole to community and society as a whole" and thus, in the particular validity of "learning to see" not only for artists and designers but to be "beneficial for all, including doctors and lawyers." Engineers he challenged to be "imagineering."

His efforts to see through the veil not only became a search for the true identity of a colour or linear construct. For him, this was a search for facts, for truth in general.

In America, the Vorkurs established the basis of some of the most influential and far-reaching art education programs of the twentieth century. It is said to have fundamentally changed the philosophy and methodology in higher art and design education. Until today, it is embedded in the Foundation Program at the reputable Rhode Island School of Design.

While the institution and idea Bauhaus as a whole could not be transplanted, even if members of the original faculty were at hand, specific programs, structures, and courses could. This applies to the "Vorkurs". It lent itself to modern art, design, and architecture programs un-bound by time and place and culture.

It focused on the fundamentals of design – materials, tools, skills and problem solving strategies, and it was built upon a universal language of geometric abstraction that gave students the vocabulary and methods to succeed in whatever workshop or design assignment they were involved. The fundamentals do not get old. And the search for the truth doesn't either.

Image is courtesy of Moholy Nagy Foundation.