Women are often edited out of the history of the Bauhaus, says Catherine Slessor, in this Opinion as part of our Bauhaus 100 series. But the role of female Bauhauslers in shaping the course of modern design is at last being addressed.

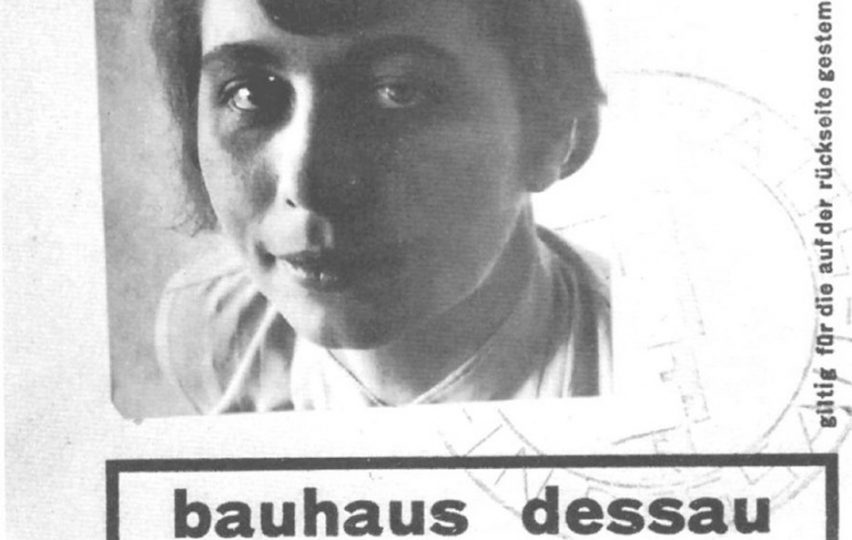

The young women of the Bauhaus seem like typical art students, when you see them in pictures. With their cropped hair and clashing clothes, they could be straight out of a prospectus for any current European art school.

But until the school's founding, German women who wanted to pursue an art education received it at home, dispensed by tutors. At the Bauhaus they were free to join courses conflating multi-disciplinary teaching with social equality, conceived as part of a fundamental reshaping of society following the first world war.

Superficially, the received image of female Bauhauslers is one of freewheeling, radical modernity, junking the literal and metaphorical corset of compliant femininity to savour the progressive pleasures of rational dress, vegetarianism, saxophone playing and photography.

Until its founding, German women who wanted to pursue an art education received it at home

Yet despite declarations of gender parity – its founder Walter Gropius insisted that there would be "no difference between the beautiful and the strong sex" when the Bauhaus opened in 1919 – the "beautiful sex" was still tacitly confined to certain "appropriate" subjects such as weaving, ceramics and toy making.

Architecture was off the curriculum, as Gropius believed women incapable of thinking in three dimensions. He was not alone in this assertion. Around the same time the female Bauhaus students were assembling on the staircase for a photocall, Charlotte Perriand was being rebuffed by Le Corbusier with a withering "we don't embroider cushions here".

Gropius's objectification of women was typical of its time, evinced by a tangled love life involving a prolonged crush on and ultimately doomed marriage to Alma Mahler, wife of the composer. Gropius became besotted, stalking the Mahler residence, and the affair drove Gustav Mahler onto Freud's couch.

In 1923 Gropius married his second wife Ise, co-author of many of his texts, but his apparently emancipatory views were undercut by a mushy medievalism with its roots in the English Arts and Crafts movement that ultimately sought to keep women in their place.

Gropius believed women incapable of thinking in three dimensions

Meanwhile, in the Bauhaus weaving studios, its nascent designers got on with creating modern textiles for fashion houses and industrial production. They included Anni Albers, now subject of a long overdue retrospective currently showing at London's Tate Modern; Benita Koche-Otte, an influential teacher and designer, whose fabrics remain in production; Gertrud Arndt, who originally aspired to study architecture, but whose rugs ended up on the floor of Gropius's office, and Gunta Stözl, who designed a series of coverings for Marcel Breuer's chairs.

Hounded by Nazi sympathisers when she married a Jewish fellow student, Stötzl left Germany in 1931 to set up a successful hand-weaving business in Zurich. She died in 1983. Her investigations into the potential of industrial fibres and dyeing technologies were accompanied by the appropriation of unorthodox new materials, including cellophane and fibreglass.

"We wanted to create living things with contemporary relevance, suitable for a new style of life", she later wrote. "Huge potential for experimentation lay before us. It was essential to define our imaginary world, to shape our experiences through rhythm, proportion, colour and form."

Gertrud Arndt's influence also extended beyond the loom, through her photographic practice. As a self-taught photographer, she began by shooting buildings and urban landscapes, as well as documenting construction sites for her architect husband. But she is better known for her powerful and disquieting Maskenportäts (Mask Portraits), which questioned the notion of female identity and formed a precursor to the work of later contemporary artists such as Cindy Sherman and Sophie Calle.

Brandt's designs encapsulate a refinement and modernity no less radical than that of her male counterpart

The early years of the Bauhaus were underscored by wrangling between Gropius and Johannes Itten, who was ousted in 1923 in favour of László Moholy-Nagy. At this point, things loosened up a bit. Painter and sculptor Marianne Brandt convinced Moholy-Nagy to allow her to pursue an apprenticeship in metalwork, a hitherto verboten discipline for women.

She went on to become one of Germany's foremost industrial designers, creating the best-selling Kandem bedside lamp, one of the most commercially successful objects to emerge from the Bauhaus. As design director of Ruppelwerk Metallwarenfabrik, she produced seductive tableware and lamps based on pure geometric forms in materials such as sliver, brass, chrome and aluminium.

From tea sets to task lights, Brandt's designs encapsulate a refinement and modernity no less radical than that of her male counterparts.

Gender stereotyping and reconciling the demands of family life were not the only obstacles to professional success. The Bauhaus's pioneering programmes and political leanings came under scrutiny from the Nazis, who eventually closed the school in 1933, accusing it of links with the Communist Party and printing anti-Nazi propaganda.

Trajectories of lives and careers were abruptly destabilised by the rise of fascism across Europe and the struggle to escape. Some, notably Anni Albers, made it to America with husband Josef, securing teaching posts at Black Mountain College in North Carolina.

Here, Albers perfected her distinctive weaving techniques, designing fabrics for Knoll and becoming the first female textile artist to have a solo exhibition at New York's Museum of Modern Art in 1949.

Histories of the Bauhaus tend to be disproportionately dominated by its male protagonists

Others remained in Europe and were subject to the calamitous fortunes of war. Benita Koch-Ott and her husband were banned from teaching in Germany and fled to Prague. Toy maker Alma Siedhoff-Buscher, one of the few women to switch from weaving to the male-dominated wood sculpture department, was killed in a bombing raid in 1944.

The fate of Otti Berger, another textile designer, is even more harrowing. While waiting for a US visa in order to join Moholy-Nagy's New Bauhaus in Chicago, she went to visit her mother in Croatia and was arrested by the Nazis. In 2005, Soviet archives revealed that Berger, who was Jewish, had died at Auschwitz in 1944.

Invariably, Bauhaus histories tend to be disproportionately dominated by male protagonists, with women receiving scant credit, perhaps best epitomised by the experience of Lucia Moholy, who was married to László Moholy-Nagy between 1921 and 1929.

As a photographer, her work helped to cultivate the image of the Bauhaus, documenting its buildings, students and teachers and experimenting with different photographic techniques. When she fled Germany in 1933, leaving everything behind, her collection of glass negatives was appropriated by Gropius who used them without credit in subsequent books and exhibitions.

After decades of legal wrangling, she finally managed to retrieve a fraction of her work in the 1960s, but was, to a large extent, edited out of Bauhaus history, a situation that seemed entirely acceptable to both Gropius and her former husband.

Such casually demeaning treatment is now being redressed by a renewed emphasis on the contribution made by the women who studied, taught and fought to be recognised. In recent years, historians and curators have sought to re-situate female Bauhauslers in their own right, rather than as marital appendages or collaborators, through the conduits of scholarship, books and exhibitions. By focusing on how they shaped both the school’s evolution and the course of modern design, a compelling new narrative emerges, illuminating the experiences and legacies of long overshadowed lives.