Researchers from the University of Wollongong in Australia have developed a 3D bioprinter that can replicate human ears for use in reconstructive surgery.

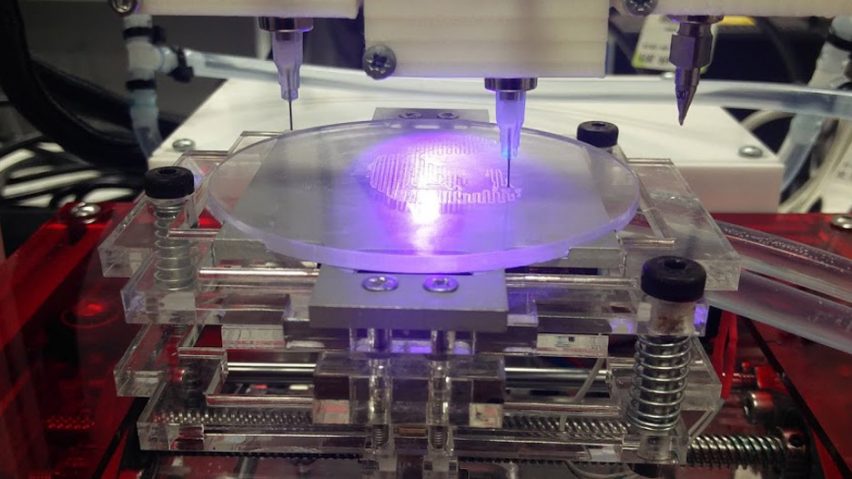

The machine, nicknamed 3D Alek, is a customised multi-materials biofabrication 3D printer, which uses a specialised bio-ink developed by researchers at University of Wollongong (UOW) and the Australian National Fabrication Facility (ANFF) to print human ears.

The bio-ink uses stem cells to grow human ear cartilage using the 3D-printing technology, to create a "living ear" for use in reconstructive surgery.

Sydney's Royal Prince Alfred Hospital (RPH) has become the first hospital in New South Wales to have the high-tech 3D bioprinter on-site.

Researchers say that this new technology brings them a step closer to revolutionising a complex medical procedure for children with microtia – a congenital condition where the external ear is underdeveloped.

"Treatment of this particular ear deformity is demanding because the outer ear is an extremely complex 3D shape, not only in length and breadth, but also in height and projection from the skull," said RPH ear, nose and throat surgeon Payal Mukherjee.

"This is where bioprinting is an extremely exciting avenue, as it allows an ear graft to be designed and customised to the patient's own face using the patient's own natural tissue," she continued.

"This would result in reduced operating time and improved cosmetic outcome – and avoids the current complication of requiring a donor site for cartilage, usually from the patient's rib cage."

Initial clinical trials saw the team use stem cells from human tissues such as nose cartilage, which is usually discarded after certain types of surgery.

However the researchers hope to continue developing the bio-ink to eventually be able to use the patient's own stem cells to grow the ear cartilage, to create a biological implant that matches the patient's own anatomy.

"We want to be able to print an ear that's customised to a patient’s individual ear abnormality and specific to a patient's own facial features," explained Mukherjee.

"This project illustrates our ability to manage a successful pipeline to turn fundamental research into a strategic application to create a new health solution to improve people's lives," said lead scientist at UOW Gordon Wallace.

"We have been responsible for the primary sourcing of materials; the formulation of bio-inks and the design and fabrication of a customised printer; the design of required optimal protocols for cell biology; through to the final clinical application," he continued.

"With one 3D Alek now established in a clinical environment at RPA and a replica in our lab at TRICEP, our new 3D bioprinting initiative, we will be able to fast-track the next stages of our research to deliver a practical solution to solve this clinical challenge," Wallace added.

This is not the first time scientists have looked to 3D-printing technologies for medical solutions. London-based design studio Cellule devised a system for creating personalised digital and 3D-printed models of hearts, to help doctors plan surgery for transplant patients.

Architects Mike Tonkin and Anna Liu also used 3D-printing to create a prototype stent that adapts to a patient's throat for use after tracheal transplant surgery.