Eugène Viollet-le-Duc's Notre-Dame spire was much loved, but it was a fake. A modern replacement could become just as revered, says Tom Ravenscroft.

Notre-Dame Cathedral will be rebuilt. French president Emmanuel Macron has promised as much and the unprecedented donations, which stand at around €850 million, means that the will and the funds are in place. But the billion dollar question is: rebuild what?

The safest option would be to replace what was lost as faithfully as possible, using the closest available materials. Notre-Dame is one of the world's most recorded buildings and the data exists to recreate the cathedral almost exactly as it was, but in better condition with an enhanced structure and improved fire protection. The numerous problems – pressure to rebuild in time for the 2024 Olympics, availability of skilled craftspeople, finding 1,300 mature oak trees – would all be overcome.

Notre-Dame will be restored to its place at the heart of the French capital, but it can not be the same building as before the fire. Even if the cathedral is faithfully restored using materials and techniques from the appropriate time periods, they will be new materials and there is no escaping that it will be a replica.

Replicating what was there before was not the option taken by architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc when he restored the building 150 years ago, and it is not what we should do now.

Viollet-le-Duc chose not replicate the original, but instead to reinvent the building with a new design to better fit his architectural ideals

When Viollet-le-Duc took over the restoration of Notre-Dame cathedral in the mid 19th century, it was, as it is now, in a ruinous state. After centuries of decline, culminating in significant damage during the French Revolution, much of the fabric was disintegrating and the building, just like now, was missing its central spire.

The original 13th-century flèche had been removed 60 years earlier to prevent it from collapsing. Viollet-le-Duc chose not replicate the original, but instead to reinvent the building with a new design to better fit his architectural ideals. It was Viollet-le-Duc's gothic-inspired timber spirelet that was spectacularly lost in last week's devastating fire, and which people are now mourning.

His spire was something he believed the original builders would have created if they had the technology and the imagination. In his view it made Notre-Dame a more complete work of gothic architecture.

"To restore a building is not to preserve it, to repair, or rebuild it; it is to reinstate it in a condition of completeness which could never have existed at any given time," wrote Viollet-le-Duc in his book the Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle (Dictionary of French Architecture from 11th to 16th century).

Viollet-le-Duc's fake spike enhanced one of Paris' most-loved buildings, and became much loved itself. A modern design to replace Viollet-le-Duc's 19th century intervention could do the same.

We can be certain that if he had had to replace the entire 13th century timber roof in the mid 19th century, he would not have faithfully recreated the historic structure

Thanks to the work of the Paris firefighters, much of the gothic cathedral was saved. Most of the original fabric from the 12th, 13th and 14th century still remains. Notre-Dame's most important architectural features – its pioneering flying buttresses, which are early use of the structural technique – still stand, as does its iconic west front.

Faced with the current restoration, what would Viollet-le-Duc do? We can be certain that if he had had to replace the entire 13th-century timber roof in the mid-19th century, he would not have faithfully recreated the historic structure. As he did with his timber needle, he would have utilised modern techniques to create a roof that he believed best embodied gothic ideals, rather than a replica of what was lost.

"In such circumstances the best plan is to suppose one's self in the position of the original architect, and to imagine what he would do if he came back to the world and had the programme with which we have to deal laid before him," wrote Viollet-le-Duc.

Placed in charge of the current restoration, Viollet-le-Duc would not hesitate to build a new roof and spire. This seems to be the course that the French government is embarking on, with prime minister Edouard Philippe announcing a contest to design a new spire that will be "adapted to the techniques and the challenges of our era".

Philippe describes the hunt for a new design as an "evolution of heritage". Just as Viollet-le-Duc added to and improved the cathedral in the 19th century, a contemporary architect should design the next stage of the building's evolution. Viollet-le-Duc was only 30 when he took over the restoration project, and ideally a young architect will design the cathedral's next chapter.

This does not mean that the essence of the cathedral should be lost, or that the new elements should dominate the medieval building – repairing the damaged stone vaults with glass would drench the cathedral in light, ruining its atmosphere and impact of the famous rose windows, while an overly tall tower would completely change the composition of the west face.

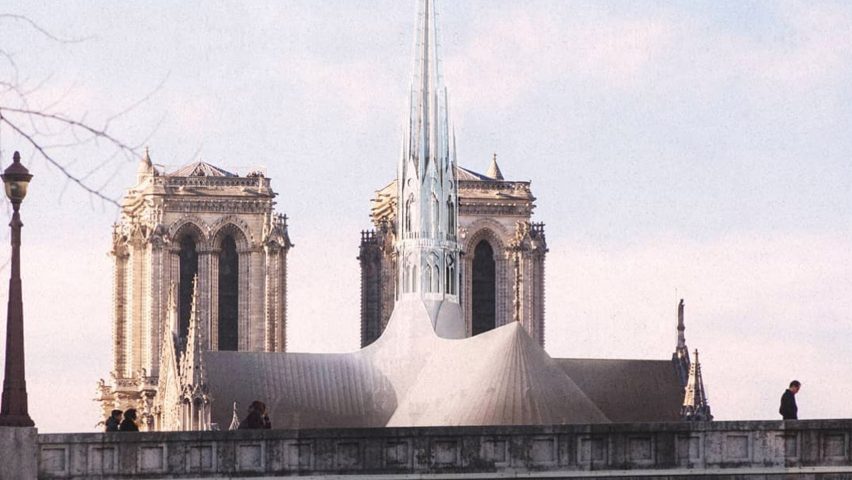

Following Viollet-le-Duc's example, the new spire and roof should have an eye on the past but be a design of the present, be based on gothic principles but interpreted with a modern eye.

Many people are already aghast at the proposed replacement spires that are emerging

This will be the most controversial option, given the cultural baggage the building carries and the expectation of donors who have pledged cash expecting restoration. Many people are already aghast at the proposed replacement spires that are emerging. As Viollet-le-Duc warned: "We must admit we are on slippery ground as soon as we deviate from literal reproduction; and that the adoption of such deviation should be reserved for extreme cases."

The combination of the country's most important building and a huge amount of donated money means Notre-Dame cathedral will be one of the most high-profile, most publicly scrutinised projects ever. And the donors, many of whom would have expected their money to be spent on a historically accurate restoration, may also be angered.

But high risk equals high reward. Paris has a history of taking occasional grand architectural leaps. These modern interventions, often into historic contexts, have often become the internationally recognised symbols of the city, none more so than the Eiffel Tower. This powerful 19th-century display of the engineering potential opened only 25 years after Viollet-le-Duc completed the restoration of Notre-Dame.

IM Pei's Pyramid at the Louvre and the Centre Pompidou are two more recent examples of the bold, modern interventions in the city. Building a modern spire at Notre-Dame would continue this tradition and could become just as loved as these monuments, or indeed Viollet-le-Duc's lost erection.

Visualisation is by David Deroo.

Join Dezeen's Notre-Dame Spire chat on Twitter, 15 May at 4 PM UK time with #dezeenchat ›