Moying Huang conceives eco-crematorium within disused London power station

Royal College of Art graduate Moying Huang has designed an ecologically friendly crematorium that would use liquid cremation to eliminate emissions from traditional incineration processes.

Named Funeral Futures, the proposed facility would be built around liquid cremation – a flame-free process where bodies are broken down in liquid over several hours.

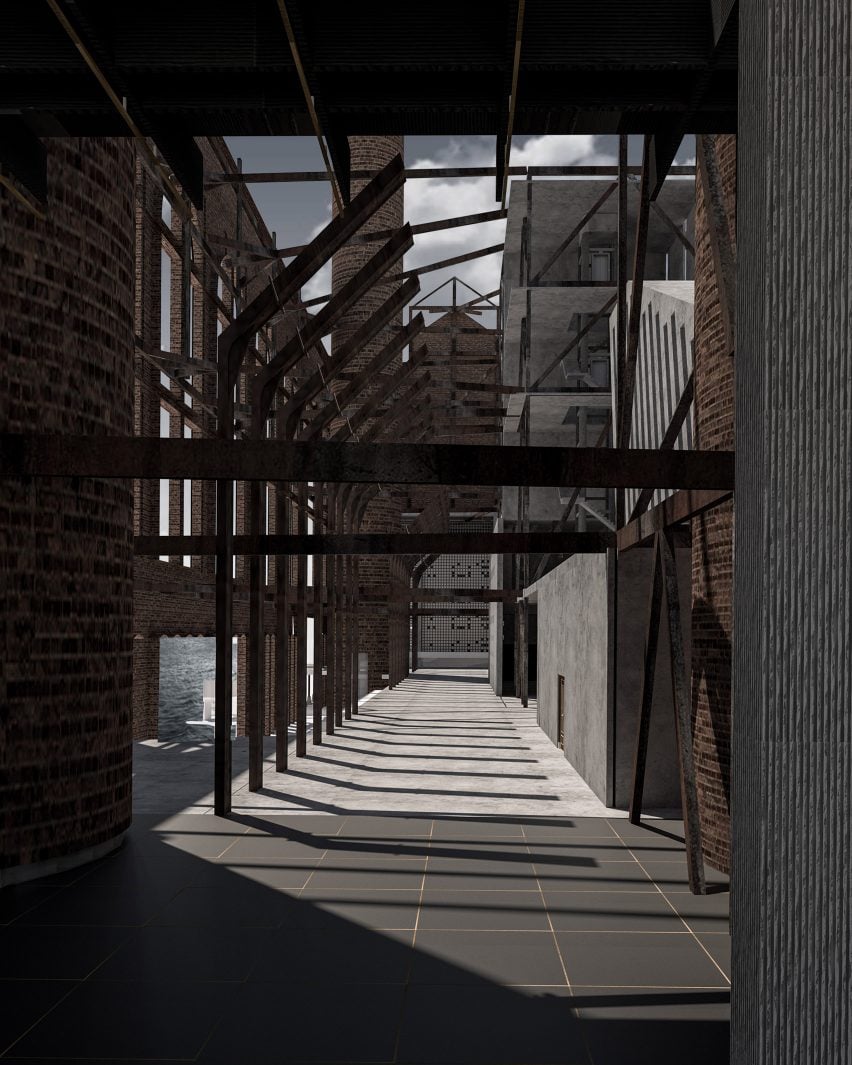

The eco-crematorium would be built in an obsolete coal and power station on Lots Road in Chelsea, London – chosen by Huang for its iconic chimneys and riverside location.

Huang proposed retaining the surviving features of the half-demolished power station and incorporating mezzanines and platforms to create contemplative spaces for mourning.

"This project imagines how the future crematorium in London in 2025 can be mutually efficient as well as emphatic," said Huang.

"Able to host three multi-faith cremation services simultaneously, this futural factory still protects the need for intimacy, privacy, ritual and ceremony that each family deserves," she told Dezeen.

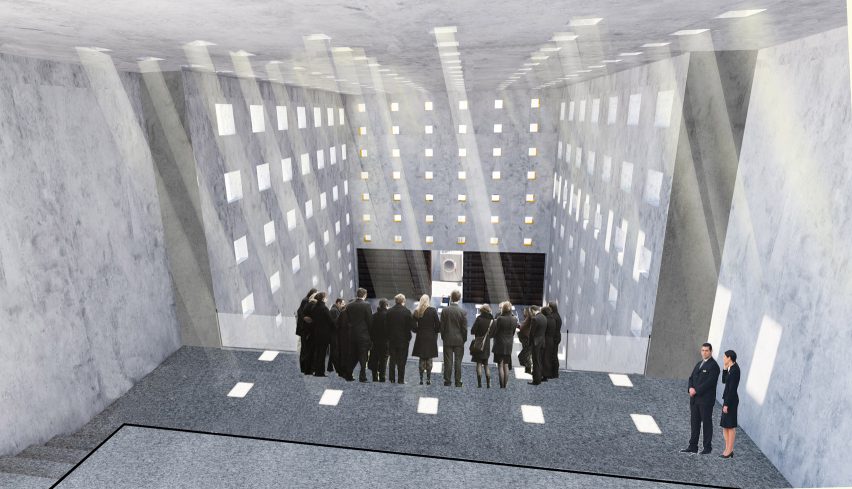

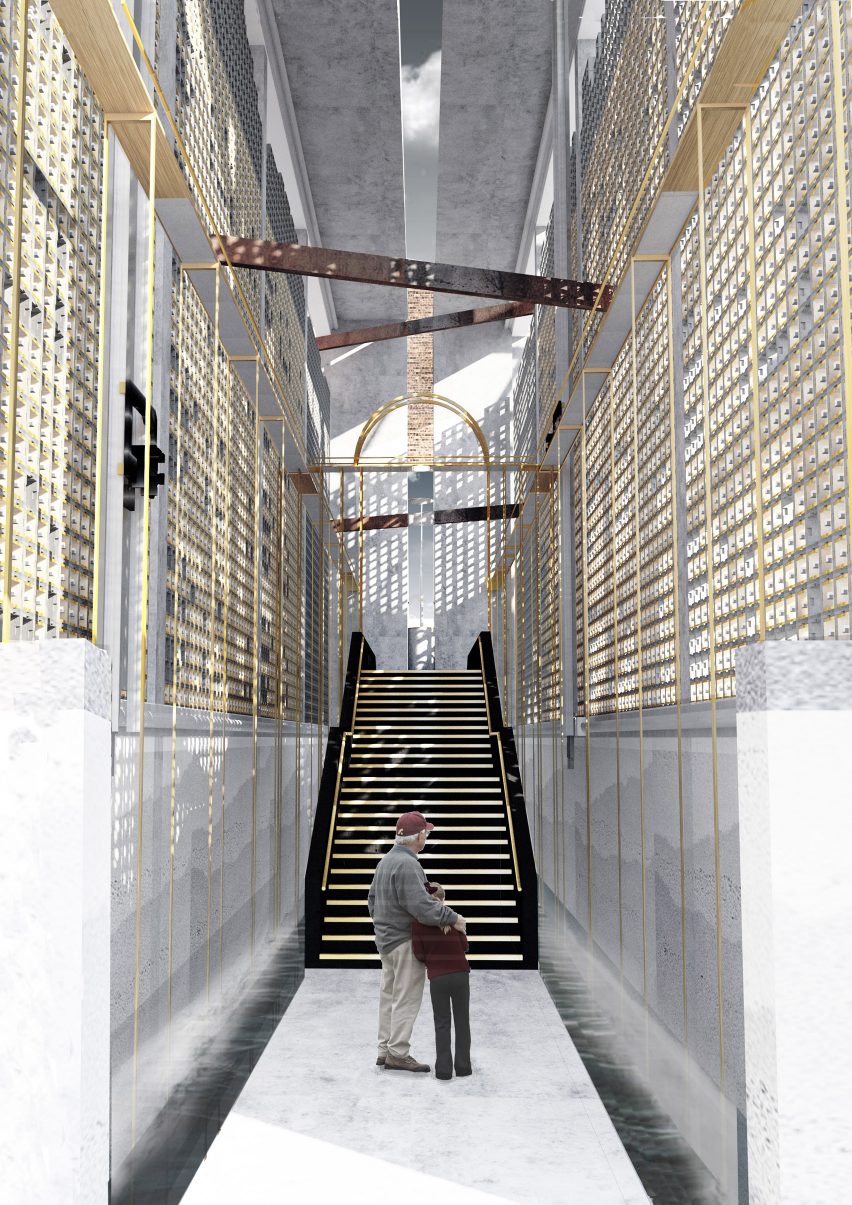

The ecologically friendly crematorium is arranged around a central atrium on the first floor, which is accessed via a grand central staircase

The large space is sliced using square columns, which continue upwards through a steel-grid structure on the ceiling. Passing through the semi-enclosed ceiling, they were designed to create varying degrees of illumination within the main hall.

"I used the light and shadow to divide the space into different areas so the mourners could choose whether they want to stand in the light area or hide themselves in the shadow," said Huang.

A chapel is placed alongside the central atrium. This area dedicated to prayer and reflective mourning would look upon the power station's metal structure and growing tree saplings placed in front of the its surviving facade.

"I wanted to reuse these former materials so that the mourners could feel the power of the existing building," she said. "The background of the chapel creates a connection and a bridge between the mourners and the dead."

A double-height viewing room is located further along the platform. Differentiated from the surrounding semi-enclosed spaces, the viewing room is fully enclosed by concrete walls, perforated with small square openings.

"This room allows the mourners to have a last farewell with their loved ones," explained Huang. From a balcony, visitors are able to view the final steps of the cremation process.

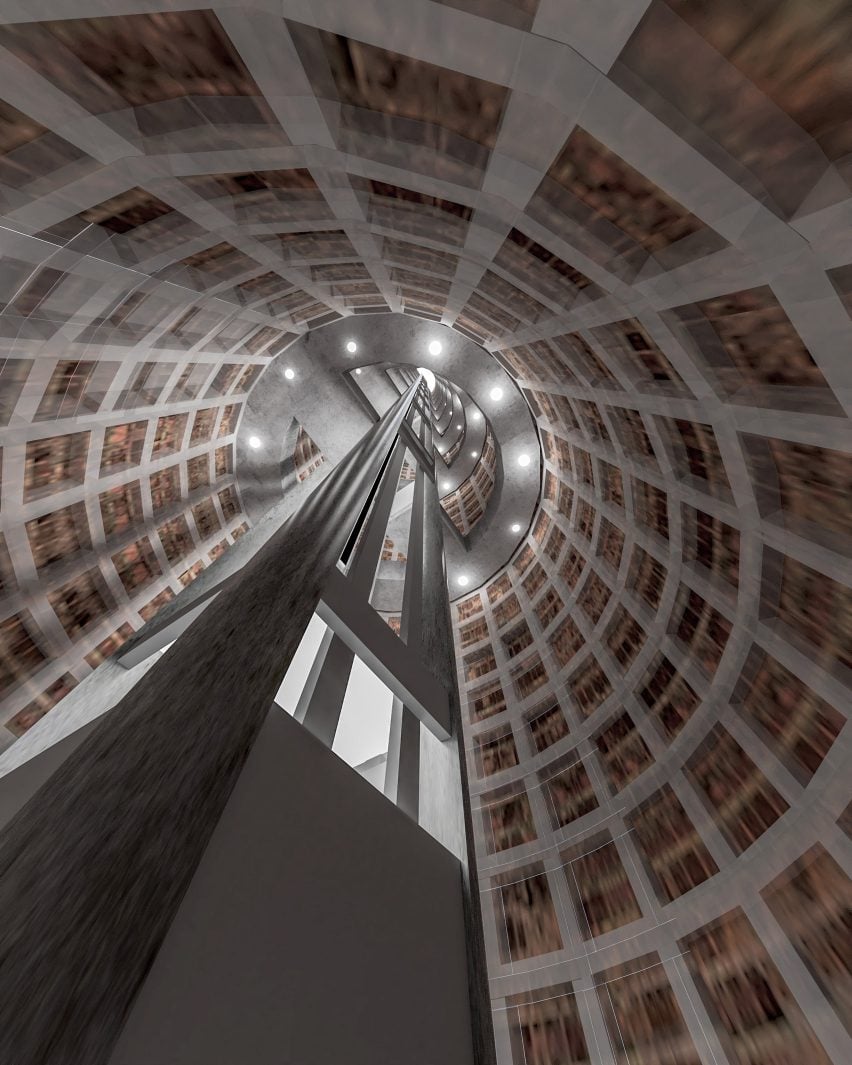

The Funeral Futures crematorium provides three options for mourners with the ashes of the deceased, intended to reduce the occupied space from traditional burial or placing urns within columbariums.

The alkaline hydrolysis process from liquid cremation doesn't destroy bones, which are then burnt creating a small amount of ash. Huang has designed spaces with the building where this ash could be converted into sculptural or wearable keepsakes.

These items of jewellery can also placed in open niches within the chimney – a remaining feature of the existing power plant – or stored within small units covering a votive wall as a private repository.

Mourners who don't want to create jewellery from the ashes can stand on a floating "water funeral" platform to scatter the them into the river.

Alternatively Huang envisions embedding the ashes into tree saplings. The graduate envisioned these trees growing into a "living memorial" that would benefit the environment rather than damaging it.

Huang's eco-crematorium proposal was completed as part of her masters in interior design at the Royal College of Art in London.

The platform group, called Interior Futures and led by Harriet Harriss, concentrates on how interiors would look according to the changing behaviours of the world. Students were encouraged to consider the natural world and its relationship with technology, whilst generating outputs to protect the environment.

As the end of the year approaches, graduates are showcasing their final projects.

Fellow Royal College of Art graduates such as June Tong proposed a thermal bath powered by Arctic cruise ship waste for her architecture course, whilst a fashion student addressed the world's overconsumption through refusing to present a final collection.