People without access to healthcare can use bicycle parts and other scrap material to make their own DIY prosthetics, using a system designed by Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology graduate Desiree Riny.

The designer created the guide after spending a year investigating the reality of how rural dwellers in developing countries managed their lower-limb amputations as part of her industrial design masters thesis project at the university.

She concluded that the latest advances in prosthetics meant little to the majority of amputees, who either cannot afford professional care or live too far away from existing services.

She found statistics that indicated 95 per cent of the world's lower-limb amputees live in such environments without access to professional care.

Beyond the issue of affording and obtaining the prostheses in the first place, the devices were sometimes unsuitable for rural environments and hard to maintain.

"Devices produced with advanced technologies such as 3D printing are often difficult to repair and not always suited to rural environments," said Riny. "Faced with these limitations, amputees find innovative do-it-yourself responses which are tailored to local materials and traditional practices."

Instead, Riny looked to the solutions that people in these communities were already using, and sought to apply current medical best practice.

Her designs use the same materials and technologies, including bicycle parts, old clothes, rice sacks, and scrap wood and metal.

"People that lived in remote communities are innovative makers when it comes to reusing different materials to make new tools for other needs or equipment to maintain their independence as a community," Riny told Dezeen.

"This revealed to me as a designer that local communities could continue to embrace these practices to fabricate a prosthetic solution that can function just like a high-costing prosthetic but at an affordable cost and with the benefits of the right medical processes."

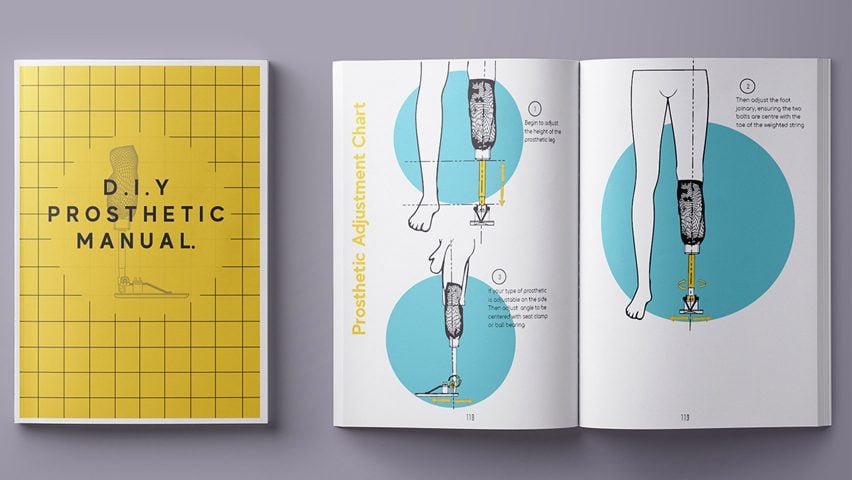

Riny's project includes three DIY lower-limb prostheses to suit different needs, as well as an illustrated manual. She imagines the manual being made available online and also distributed through local businesses and NGOs.

One of the prostheses barely moves at the foot joint but offers a high degree of stability. The other two offer more than 30 degrees of movement, using a bike seat rail for the joinery.

Riny points out that in countries including India, Cambodia and South Africa, bicycles are a key mode of transportation and people are familiar with taking them apart.

There is also an innovative solution for the sockets involving high-tensile fibres from everyday objects such as the hemp from rice sacks.

Riny reinforces these with resin and synthetic fibres from reused clothing, although the process is adaptable to many different kinds of materials, depending on what is locally abundant.

"This allows for a closed-loop solution where the prosthetic can be repaired, adjusted and fabricated in the community, without having to be reliant on external services or deliveries for certain parts, or medical experts to adjust a single screw," said Riny.

Riny's thesis is titled Reclaiming Accessibility: To Lower Limb Prosthetics. Her research spanned communities in Sudan, South Sudan, Cameroon, India and Cambodia.

And while she was not able to visit these places firsthand during her one-year graduate project, she had turned her vision into a start-up that is currently raising funds for travel so that the next-stage of the process can involve co-designing with remote communities.

The start-up is being supported by RMIT's Activator, the university's incubator.

Other designers have also recently focused on low-cost solutions for lower-limb amputees. Fabian Engel and Simon Oschwald came up with Project Circleg, which uses recycled plastic waste, while a team at MIT engineered a streamlined prosthetic customisable to a user's height and weight.