"We fooled ourselves that sustainability was getting us where we needed to go" says Michael Pawlyn of Architects Declare

Architects must urgently go beyond creating sustainable architecture that minimises damage to the planet and design buildings that help repair it, says Michael Pawlyn from Architects Declare.

Biomimetic architect Pawyln, who has played a key role in promoting Architects Declare, believes that architecture that "just mitigates negatives" is not going far enough.

"We all fooled ourselves that sustainability was getting us where we needed to go and it was all making everything better," he told Dezeen.

"There's something inherently problematic in the framing of sustainability that implies the best you can aspire to is neutrality, and anything less than that is just part of a degenerative downward cycle."

Pawlyn says that if the industry is to truly help tackle the multiple environmental challenges of today, architects must design buildings that give more than they take.

"We urgently need to look at means to be regenerative"

Pawlyn believes the solution is regenerative design – the development of restorative and renewable systems where output is always greater than input, beneficial for humans and other species.

"We urgently need to look at means to be regenerative, which is to get into a positive cycle in which everything we do we're trying to have a positive impact – in terms of restoring ecosystems, taking carbon out of the atmosphere, regarding communities and so on," he told Dezeen.

However architecture is currently stuck in the "outdated mitigation paradigm" where, at best, studios are striving for architecture that does no additional harm to the environment and only sustains its own existence.

Part of the problem, he believes, is green building standards like LEED and BREEAM that accredit buildings for achieving neutrality. Instead, standards like the Living Building Challenge that promote regenerative design should become compulsory.

"We all thought we were making things better, and it's painful to accept that most of that time we were just making things slightly less bad," he added.

"If we're to address the challenges of the present day, then we need a functional revolution."

Biomimicry likely "to deliver those breakthroughs"

In Pawlyn's opinion, the best way that architects can create regenerative architecture is by using biomimicry.

Biomimicry is a functional discipline that translates functions and processes found biology into solutions that meet human needs, which Pawlyn has been championing since 2006 when he established his studio Exploration Architecture.

In architecture, this can range from replicating animal skeletons to make more efficient structures through to mimicking entire ecosystems to manage water, waste and energy more efficiently.

"We're at a pretty dramatic time in history, where if we continue with our view of nature as something to be conquered and plundered, then we're in deep trouble as a species," Pawlyn said.

"That's one of the exciting things about biomimicry, it points towards a very different relationship with nature, looking to nature as a source of wonder and as a source of some of the best solutions that we need to tackle the challenges of the present day."

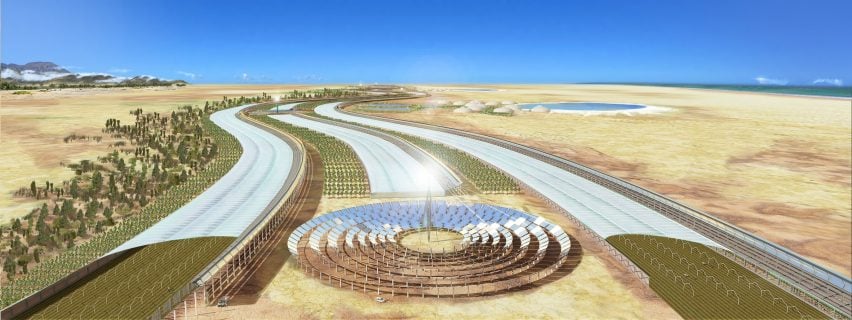

An example that Exploration Architecture has created to demonstrate these ideals is The Sahara Forest Project in Qatar – a seawater-cooled greenhouse modelled on the Namibian fog-basking beetle, an insect that harvests its own fresh water in a desert.

The greenhouse, which is powered by solar energy, replicates the beetle's physiology to create freshwater to grow crops inside, with any excess used to revegetate the surrounding desert landscape.

"We have all of the solutions we need to make really rapid progress on these things, so there's definitely not a lack of solutions," added Pawlyn.

"The problem is with the dominant view on nature, the current economic paradigm, with a great deal of inertia and with us still being stuck in the sustainability paradigm of mitigating negatives."

Architects Declare signatories must "follow up"

Since launching in May, Architects Declare now has over 600 signatories in the UK, and hundreds more internationally.

Pawlyn spoke exclusively to Dezeen ahead of the group's first gathering in November, during which there will be a series of robust discussions about how to address the emergency. He hopes it will "set the bar high" in terms of the level of change required.

"We thought we'd have to work really hard to get 100 practices signed up in the first two months so we could then go to the RIBA to get them to declare. Actually, we had 200 firms signing up in the first two days," Pawlyn said.

"Now it's very important that we follow up. We are having a gathering in November for UK signatories in November and the aim there is to discuss what we need to do," he continued.

"To put it in the language of Greta Thunberg, which is very useful in its directness, the 'house is on fire'. And we need to work out how to help put it out. "

This year has seen a sharp rise of climate awareness after the United Nations warned that humanity has 12 years to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, or risk catastrophic changes to the planet.

Architects Declare was launched by 17 Stirling Prize winning architecture firms, including Zaha Hadid Architects, David Chipperfield Architects and Foster + Partners, in response to encourage all UK architects to adopt a "shift in behaviour".

The Royal Institute of British Architects later followed suit, declaring a state of climate emergency in June and committing to a five-year plan of action for climate change.

Read on for an edited transcript of the interview.

Lizzie Crook: Tell me about your background. How long have you been involved in sustainable architecture?

Michael Pawlyn: So I guess in some ways it goes all the way back to when I was a teenager and I was passionate about three things: design, biology and the environment. I had thought about studying biology at university but I couldn't see the creative side of it. I left that behind and studied architecture. I went to the Bartlett and then I did my year out at Bennetts Associates, in the very early days of Bennetts Associates.

I then took a second year out and studied in Japan with Takao Ando, I came back finished my course at Bath. Then I joined…well actually I worked for a TV documentary company briefly, then I worked at Haworth Tompkins.

And then I had the opportunity to join Grimshaw in the early stages of the Eden Project, which was a fantastic experience. At that stage David Kirkland at Grimshaw had come up with the idea of the intersecting spheres. My role as project architect of the biomes was to take that idea and take it through all the testing, approval stages and design stages through to completion, which was a wonderful learning experience, learning how to take something pretty far out and go through the innovation stages necessary to make it real.

Lizzie Crook: And today your expertise lies in biomimicry?

Michael Pawlyn: Yes.

Lizzie Crook: So was the Eden Project your way into that?

Michael Pawlyn: It was actually. It was working on the Eden that made me realise there was a way to bring together these three strands: design, biology and the environment. And then after we finished the Eden Project I went on a five day course at the Schumacher College with two absolute luminaries – Amory Lovins from the Rocky Mountain Institute and Janine Benyus. I reckon I learnt more in those five days than I had done in the previous 15 years of going to conferences and listening to architects.

Lizzie Crook: So what exactly is biomimicry? Can you explain what it means through the lens of architecture?

Michael Pawlyn: Sure. The simple way of describing biomimicry is innovation inspired by nature. So it's looking at the way that functions are delivered in biology, or biological adaptations, and learning from those adaptations and translating that into something that suits human needs. So it's very much a functional discipline and it's distinct from some of the other biologically-inspired approaches.

I'm convinced that if we're to address the challenges of the present day, then we need a functional revolution

So I draw a clear distinction between biomimicry and biomorphism – so biomorphism is alluding to biological forms for symbolic effect. And there are some very effective pieces of architecture like that, you know like Saarinen's TWA terminal, and Frank Lloyd Wright's Johnson Wax building. But, I'm convinced that if we're to address the challenges of the present day, then we need a functional revolution. And it's much more likely to be biomimicry that delivers those breakthroughs than say, biomorphism or biophilia.

Lizzie Crook: What exactly can we learn from nature?

Planet Earth is about 4.5 billion years old and the first life forms appeared about 3.8 billion years ago. Since then, there's been an almost endless process of evolutionary refinement that has resulted in some amazingly refined solutions. So we can look for instance to nature to inspire very efficient structures, we can look to biology for a lot of the solutions we need for the circular economy, rethinking the way we make things, the way we use materials that are easy to keep within closed loop cycles.

There's also a lot we can learn from processes in biology, processes such as harvesting water in arid regions, or keeping warm, keeping cool. Even surprising ones like fire protection, you can find some quite amazing solutions in biology.

One of the, I think, most important chapters of my book Biomimicry in Architecture is about designing zero-waste systems. So looking at the characteristics of ecosystems and seeing how we can shift conventional human-made systems towards the characteristics of ecosystems.

I can expand on that if you want?

Lizzie Crook: Perhaps you could contextualise it. What's the most exciting example you've worked?

Michael Pawlyn: So the Sahara Forest Project, that was something I initiated about 10 years ago. That was conceived as a synergy between three main technologies. Those were forms of solar energy, a sea water-cooled greenhouse and desert revegetation techniques.

When we came to build the first version in Qatar, we were able to expand that cluster of technologies. We looked at each of those technologies in terms of their resource flow – what was coming in and what was going out. Any resource flow that is under-utilised, that's a sign that you could add something to the system to give it more value.

So it gets quite complicated. Just like an ecosystem, you've got a lot of interconnections and interdependencies between these technologies. And we had about, I think, about 10 different technologies on the Sahara Forest Project Qatar and we were working hard to tune all the connections between them. And the great thing about that approach is that it moves towards being a highly productive, zero-waste system that runs entirely on solar energy and importantly is regenerative, rather than extractive.

Lizzie Crook: So by using biomimicry you created regenerative architecture – using approaches like this could help us tackle the current climate and ecological crises. As the general focus in sustainable architecture seems to be mitigation how do we make approaches like biomimicry mainstream?

Michael Pawlyn: That's a really good question, and you've touched on one of the most important shifts that we need to bring about, and that's a paradigm shift from sustainable design to regenerative design. And yes, as you say, sustainability has far too often been about just mitigating negatives. We all thought we were making things better, and it's painful to accept that most of that time we were just making things slightly less bad.

There's something inherently problematic in the framing of sustainability that implies the best you can aspire to is neutrality

I came to the conclusion in October last year that we need a series of paradigm shifts so just sticking with the sustainable to regenerative model for a moment, there's something inherently problematic in the framing of sustainability that implies the best you can aspire to is neutrality, and anything less than that is just part of a degenerative downward cycle.

So we urgently need to look at means to be regenerative, which is to get into a positive cycle in which everything we do, we're trying to have a positive impact – in terms of restoring ecosystems, taking carbon out of the atmosphere, regarding communities and so on.

And I think, just as we all asked questions 20-30 years ago about what we'd need to achieve the ultimate in sustainability, now we should be asking that question about regenerative design, how do we achieve the absolute optimum of regenerative design? And I'm convinced that a lot of those solutions are going to come from biology-inspired approaches – principally biomimicry and biophilia.

Lizzie Crook: Are there technologies available to do so? Can they be implemented at the speed at which we need to change?

Michael Pawlyn: Well there are some tantalising solutions that are still slightly outside our grasp. So for instance, biology has evolved a way to make glass with higher optical quality than we do, with many orders of magnitude less energy – probably one-ten-thousandth of the energy. And similarly, concrete – the nearest equivalent to concrete in biology is coral reefs. So that's a large-scale mineral structure, but corals grow by taking carbon out of the environment rather than emitting it.

There are now one or two examples of that, so there's a company called Blue Planet who found a way of making aggregates from flue gases, so that's taking carbon out of the flue gases and turning those into a solid form. But we need to find lots of other ways of taking carbon out of the atmosphere. Timber is an obvious one, but there are others coming along as well.

Sorry, I've slightly lost the thread! Remind me what the question was?

Lizzie Crook: That's ok! So are the technologies that we need to become regenerative there, and is there time to implement them, basically.

Michael Pawlyn: Yes, ok. There are some that are sort of tantalisingly slightly beyond our reach, and we need to be investing research and development in those.

However, there's a huge plethora of solutions that we can implement immediately – and that's what I catalogued in my book. So looking at all the solutions we could use to make efficient structures, using materials better, create zero-waste systems, manage water, thermal regulation, how to manage energy... and I've noticed there's often quite a range of depths with which you can apply biomimicry.

A good example would be [Exploration Architecture's] office building, the biomimetic office. So one of the sources of inspiration was a fish, called a spook fish, which has mirror-shaped structures in its eyes. That led to the idea of this pair of reflective surfaces in the atrium that bounce light into the other parts of the building – so that was pretty obvious, that was a straightforward translation of an idea in biology into architecture.

In the same process of trying to design the building to be completely naturally lit, we looked at a lot of other examples. One of which was the rainforest plant, which lives in low-light levels and has lenses over its leaves. Somehow those are able to focus diffused light and that gave us the idea of focusing light into fibre-optic tubes that we could duct then around the building. And focusing diffused light - that is really pretty challenging scientifically, and there wasn't scope to pursue that fully within that project stage so to do that properly that would require a research project involving whoever the world expert on that particular plant is, there would be some specialists in light and objects, maybe a biologist as part of the design team as well to help make the translation between biology and design.

So you can see there are quite obvious ways as well as much more scientific ways - so for me both of those, and everything in between is perfectly valid.

Lizzie Crook: So should architects be working with scientists now to really move things forward?

Michael Pawlyn: There's certainly a lot to be gained from working with scientists. Often architects seem more inclined to collaborate more with cultural collaborators. I've found it enormously rewarding working with scientists, and often those scientists have been exploring something really fascinating and haven't necessarily seen how it could be applied in a way that could make a real difference to people's lives. So it can be it can be very enjoyable.

I think it is time architects started collaborating more with scientists

Yes, so, I think it is time architects started collaborating more with scientists in order to bring more of those solutions into the mainstream of architecture. For some reason biomimicry's been quite slow to be adopted. It's been adopted quite rapidly in fields like robotics and medicine and sportswear design, and I'm not quite sure why it's not made significant inroads into the mainstream of architecture yet. I think perhaps because it's still sort of seen as bit gimmicky maybe? And often that's sort of the way it's done, it invites criticisms of being slightly superficial, but for me it's not that at all. It's actually a rich source of solutions with an endless depth and beauty.

Lizzie Crook: What are the barriers that are stopping us from adopting these approaches? Is it governmental or does it come down to people's attitudes?

Michael Pawlyn: That's a big question. In October last year after the IPCC report I reread a really important essay by Donella Meadows called Leverage Points in which...she was a systems thinker, one of the greatest systems thinkers of all time. And in that essay she talks about how, because our systems are inherently complex, it's not always obvious where to intervene in order to bring about the change. She argues convincingly that too often we apply the lever in the wrong place, and she draws up a list of 12 places we can intervene and some of the areas that I previously thought are influential are a long way down on the list.

High up on her list are paradigm or mindset out of which system behaviour emerges, and then below that is changing the goals for the system. And that's what I've been focusing quite a lot of my time on since October – getting actively involved with Steve Tompkins on Architects Declare and also writing a book that I'm co-authoring with Sarah Ichioka which is about paradigm shifts.

When I first set up [Exploration Architecture], I thought the main problem was a lack of good implemented solutions and that if we just got good teams together, talked positively about solutions it would all happen, and actually that's not gonna happen if there are problems at a higher system level.

If we continue with our view of nature as something to be conquered and plundered, then we're in deep trouble as a species

So we're at a pretty dramatic time in history actually, where if we continue with our view of nature as something to be conquered and plundered, then we're in deep trouble as a species. And that's one of the exciting things about biomimicry, it points towards a very different relationship with nature, looking to nature as a source of wonder and as a source of some of the best solutions that we need to tackle the challenges of the present day.

Another aspect of the present day that's weird is that we have all of the solutions we need to make really rapid progress on these things, so there's definitely not a lack of solutions. The problem is with the dominant view on nature, the current economic paradigm, with a great deal of inertia and with us still being stuck in the sustainability paradigm of mitigating negatives.

Lizzie Crook: As you mentioned, one of your most recent endeavours has been being actively involved in promoting Architects Declare with Steve Tompkins, which was launched by the Stirling Prize winners. Why was now the time to establish it, had you had thoughts of doing so before?

Michael Pawlyn: I guess I was concerned that there wasn't enough of a response to the IPCC report, it all seemed very quiet from architects and I wrongly assumed there wasn't a higher degree of concern. It was very satisfying that as soon as Architects Declare was launched by the Stirling Prize winners, it took off at an amazing speed. We thought we'd have to work really hard to get 100 practices signed up in the first two months so we could then go to the RIBA to get them to declare.

Actually, we had 200 firms signing up in the first two days. And now its over 600 in the UK, over 500 in Australia, it's really gone quite international. We've got Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Norway, Italy...and we've got some others in the pipeline as well. So it's been more successful than you could ever imagine.

Now it's very important that we follow up. We are having a gathering in November for UK signatories in November and the aim there is to discuss what we need to do. To put it in the language of Greta Thunberg, which is very useful in its directness, the house is on fire. And we need to work out how to help put it out.

Lizzie Crook: You were surprised by the uptake – why do you think it's taken so long for people to take climate change seriously?

Michael Pawlyn: I think we all fooled ourselves that sustainability was getting us where we needed to go and it was all making everything better. And as is often the case, when you realise something, a lot of people are going to be wondering now why it took us this long to come to the realisation that sustainability was flawed.

Lizzie Crook: As you said, Architects Declare now needs to be followed up with action. Some signatories are currently working on projects like airports. How do we ensure architects are following through on their promises?

Michael Pawlyn: Well we've deliberately decided we're not going to do any naming and shaming, but instead just set the bar high in terms of the level of change required. And we're anticipating that it is going to be self-policing to a large extent. That's something that we'll take a look at.

So we've got a steering group now for Architects Declare and we're going to review how it goes, we're going to share as much knowledge as we can both within the UK signatories as well as with some of the other countries that have declared to give them a better chance of succeeding and spreading the idea overseas.

We're deliberately taking a fairly decentralised approach, we're not trying to be controlling.

Lizzie Crook: Last week at the Architecture Foundation's Architecture of Emergency event the general consensus was that we need to see this catastrophe as an exciting design challenge. What's your stance on that, how optimistic are you?

Michael Pawlyn: I went to it, I thought it was a good event. Well organised with a good diversity of voices. I hope that is only the beginning, so to borrow a phrase from Naomi Klein, this changes everything. We need to talk about how architecture is taught, how it's covered in the media, how it is practiced, regulated and celebrated, and any one of those threads could form the basis for a similar evening of discussion.

There's nothing inevitable about the future

In terms of optimism, well one of the chapters in the book I'm writing with Sarah Ishioka is arguing that we shouldn't be pessimistic or optimistic. What we should be is "possibilists". That was a term coined by Hans Rosling, and his point was that optimisim or pessimism implies there's some sort of inevitability about the future, and there's nothing inevitable about the future.

What we should be instead is very serious possibilists. We should decide on the future we want, based on rigorous evidence-based thinking, and then set about creating that. And I think one of the really important things we need to do is think about how we can maximise our agency.

I think there's a been a tendency for everyone, not just architects, but in all fields, a tendency to minimise their agency, and think that they can't do 'X' unless someone else does 'Y'. And so very often architects say "we can't do a regenerative building unless the client wants it". And the client says, "well we're commercial company, we have to answer to our shareholders, we can't do anything unless our shareholders do it".

I was at an event last week at which a head of an oil company said "we have to operate, we can't do anything that's going to put us at a disadvantage." And that kind of thinking is going to get us more and more deeply into trouble. And that oil company boss, if he's actually convinced it's now serious, then what he should be doing is getting together with the other oil companies and saying that "none of us can act equilaterally, we need to talk to governments and set a new level playing field so we can make really rapid progress." And similarly architects and clients need to look at how they can maximise their agency. And it's only by all of us maximising our agency that we can bring about the rapid and dramatic shifts.

Lizzie Crook: Do you have any final advice for architects? What changes can they implement today to make a difference to the climate catastrophe?

Michael Pawlyn: Difficult to give a single answer to that really... I do think it's important to gain an understanding of the big shifts that we need to bring about. There are one or two really important books that are worth reading – I recently read The Patterning Instinct by Jeremy Lent, it's genuinely one of the most important books I've ever read and I would recommend that to all architects.

At a more practical level we need to be aspiring to go well beyond LEED and BREAM, for me those are both very much in the outdated mitigation paradigm, and the best kind of building standard is the Living Buildings Challenge. So if you can persuade your clients to go for the Living Buildings Challenge that's going to take us much closer to the regenerative aims that we need to be getting to.

Lizzie Crook: What's next for you?

I'm working on a range of scales. I've always done a certain amount of consultancy and I'm still doing that. I've been advising the Singapore government on biomimicry and the circular economy.

At the other end of the scale I'm working on one quite small retail project for some really progressive clients who want to push the idea of regenerative design. Hopefully going to be starting on a pavilion that is inspired by bird skulls.

We made a 3D-printed model of a section of bird skull, which I was absolutely delighted with. It really captures the beauty and resource efficiency of bird skulls and we're hoping to do a pavilion based on that using 3d printing, which incidentally is a huge asset for biomimicry. 3D printing allows us to get much closer to the way things are made in biology. In biology you can often see structures that achieve their efficiency through really quite complex forms, putting material exactly where it needs to be.

Conventionally, that was always more expensive, that kind of complexity. But now with 3D-printing that kind of complexity should in theory be cheaper because you can use far less material, you just put it exactly where it needs to be.

Portrait photo is by Kelly Hill.