"Surviving on Mars could teach us how to live more sustainably on earth", says Design Museum's Moving to Mars curator

The Moving to Mars exhibition, which opens tomorrow at London's Design Museum, explores putting humans on the red planet as the final frontier for design.

The show is structured into five parts: Imagining Mars, The Voyage, Survival, Mars Futures and Down to Earth.

It explores themes including the role that design plays in keeping astronauts safe during the voyage to Mars, and what working with its limited resources could teach us about designing more sustainably on Earth.

"We don't advocate for Mars as a Planet B," said the exhibition's curator and Dezeen columnist Justin McGuirk.

"But we pose the question of whether the rigours required in such an inhospitable environment – where we'll have to recycle our oxygen, recycle our water and reuse our waste to survive – might force us to solve those problems on Earth," he continued.

"Here, despite everything, we can all still get up and go through our day and not change anything. You cannot do that if you're sending someone to Mars because they wouldn't last one minute."

How survival on Mars might become possible is explored through more than 200 exhibits.

These consist of a combination of original artefacts from the likes of NASA and Elon Musk's SpaceX, alongside new commissions and immersive installations by Konstantin Grcic and Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg.

"We've gathered a lot of the real work going into the Mars mission by practising architects and designers," McGuirk told Dezeen. "But we took it even further and invited a number of designers to think through possible future scenarios."

"Their work adds a layer of design fiction to the exhibition, which is a great tool for taking ideas and making them concrete, and material," he continued.

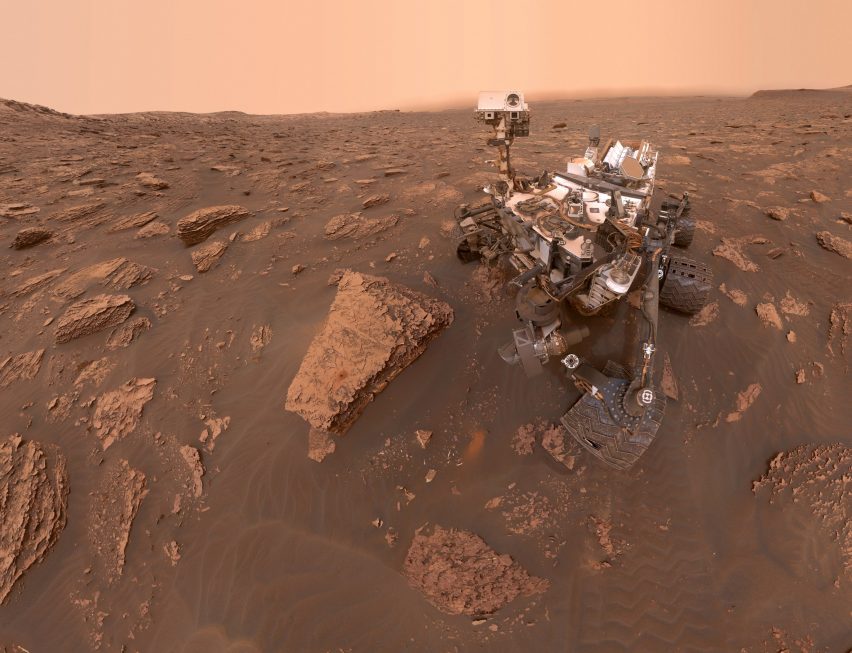

The show's first section, Imagining Mars, charts our fascination with the red planet throughout history and culture, and how our understanding of it has been shaped through scientific advancements.

This covers everything from the first real maps of Mars, created by Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli in the 1870s, to a prototype of the Rosalind Franklin ExoMars Rover which will be sent to the planet in 2020.

Named after the scientist whose x-ray images let to the discovery of DNA, this mobile laboratory created by the European Space Agency (ESA) and its Russian counterpart Roscosmos, will drill two metres into the planet's surface to look for evidence of past or present life.

This is followed by On Mars Today, a multi-sensory installation meant to help visitors imagine the current conditions on the planet, from the radiation to the freezing temperatures, the lack of oxygen and the frequent dust storms.

It visualises these conditions through a slowly panning panorama of the Martian environment, accompanied by an audio track of otherworldly sounds and a scent created especially for the exhibition by perfumery Firmenich.

Part two of the exhibition takes a closer look at how we would actually get to Mars, starting from the first iterations of space travel and going on to explore how it might be adapted for the journey to Mars.

"It took us three days to get to the moon, so how can we stay safe and sane on a seven- to nine-month journey to Mars?" asked McGuirk. "Add to that the time needed for the scientific study of the planet and it's a completely different prospect."

"It's not just about making sure that people can be kept healthy and fed. It's also about making it tolerable," he continued.

This shift to a more human-centred approach is explored through seminal interior designs created for both NASA and the Soviet space programme.

Sketches by American designer Raymond Loewy illustrate his introduction of windows, which had previously been considered a structural weakness, as well as a dining table to facilitate communal eating.

Alongside this sit designs from Russian architect Galina Balashova, who first introduced the colour coding of floors and ceilings to help astronauts maintain a sense of orientation.

This part of the exhibition also considers the constraints of zero gravity, which require everything from basic equipment to furniture to be re-designed.

A new commission by German industrial designer Konstantin Grcic simplifies the highly engineered and complex tables present in spacecrafts and on space stations today as a circular rail. Astronauts' feet are hooked into floor-mounted straps to anchor them.

Designer Anna Talvi, meanwhile, has contributed a series of lightweight, flexible garments, which act as a sort of "wearable gym" working out the wearer's muscles to prevent them from atrophying in low gravity.

On display for the first time as part of the exhibition is NDX-1, the first prototype spacesuit designed specifically for use on Mars.

It was created by the University of North Dakota to withstand the planet's gruelling conditions, while soft fabric-joints improve mobility when compared to the suits used on the moon.

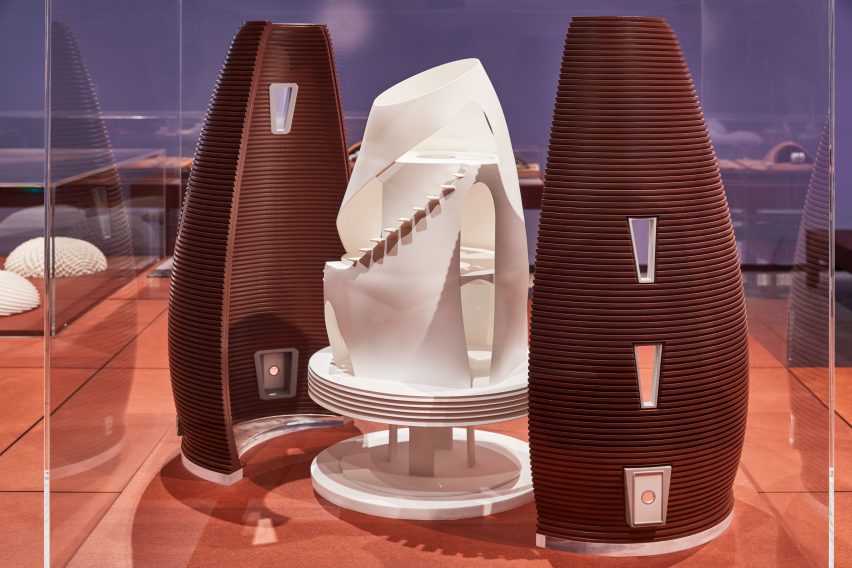

In part three, designers turn to the matter of survival – namely where we will live, what we will wear and eat.

Here, a large space is designated to different miniature models of what a future habitat could look like, including a 3D-printed habitat designed by Foster + Partners, as well as a full-sized, walk-in model made by architecture firm Hassell.

Both make use of Mars' loose, sandy topsoil, called regolith, to form a protective outer shell, while inflatable pods are used to form the interior.

Fashion studio Raeburn has contributed its New Horizons collection, which responds to the lack of resources on Mars through a "make do and mend" approach, repurposing solar blankets and parachutes into clothing.

Usually, GrowStack specialises in growing food beneath the surface of the earth in one of the world's first underground farms.

But for this exhibition, the vertical farming company is taking its methods into space, exploring how a hydroponic system – which is not reliant on soil and uses less water and space while creating a larger yield – might be useful on Mars.

Meanwhile designer Franziska Steingen has created a home grieving set, which considers new ways of burial in a future where bodies cannot be sent back to earth.

It consists of a candle placed under a glass dome, with the soot generated through repeated burning gradually blackening the glass as a way of visualising grief and remembrance.

The final two parts of the exhibition – Mars Futures and Down to Earth – pose concrete questions about the future.

On the one hand, possible alternative routes are explored, such as habitable pods suspended in space, as well as a version of Mars populated by plants instead of people via an installation by designer and artist Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, who will give a keynote talk at Dezeen Day on 30 October.

Her computer simulation tracks a million years in the space of an hour, to imagine how sending 16 different species of bacteria and plants to the planet could lead to a myriad of different possible biospheres as they interact in unexpected ways.

Finally, the last section invites visitors and contributors to ponder the ethical and existential dilemma at the heart of the exhibition: should humanity actually go to Mars?

Moving to Mars will be one of the last exhibitions overseen by the Design Museum's current co-directors Deyan Sudjic and Alice Black, after announcing their departure at the start of October.

The museum's new director and first ever CEO Tim Marlow will step into the role as of January 2020.

Photography is by Ed Reeve unless otherwise stated.