Chiara Tommencioni Pisapia uses moths to transform unwanted clothing into "precious" bio-waste material

Central Saint Martins graduate Chiara Tommencioni Pisapia has proposed a method for improving the textile recycling process by using moths to break down the natural fibres in discarded clothing.

Pisapia, who says she is "interested in sustainability related to fashion, textile recycling, bio-design and the circular economy", wanted to find a more efficient way to deal with mixed-fibre textiles, which are currently complicated to recycle.

These textiles, containing a combination of manmade and natural fibres such as wool and polyester, typically end up in landfill or incinerators as it is difficult to separate the fibres for recycling.

"Textile recycling is currently done mainly using chemicals or mechanical methods," the designer told Dezeen.

"As we are in a time where biology and design are interweaving, I thought it would be interesting to explore how nature is recycling and breaking down fibres and this brought me to look at clothes moths," she added.

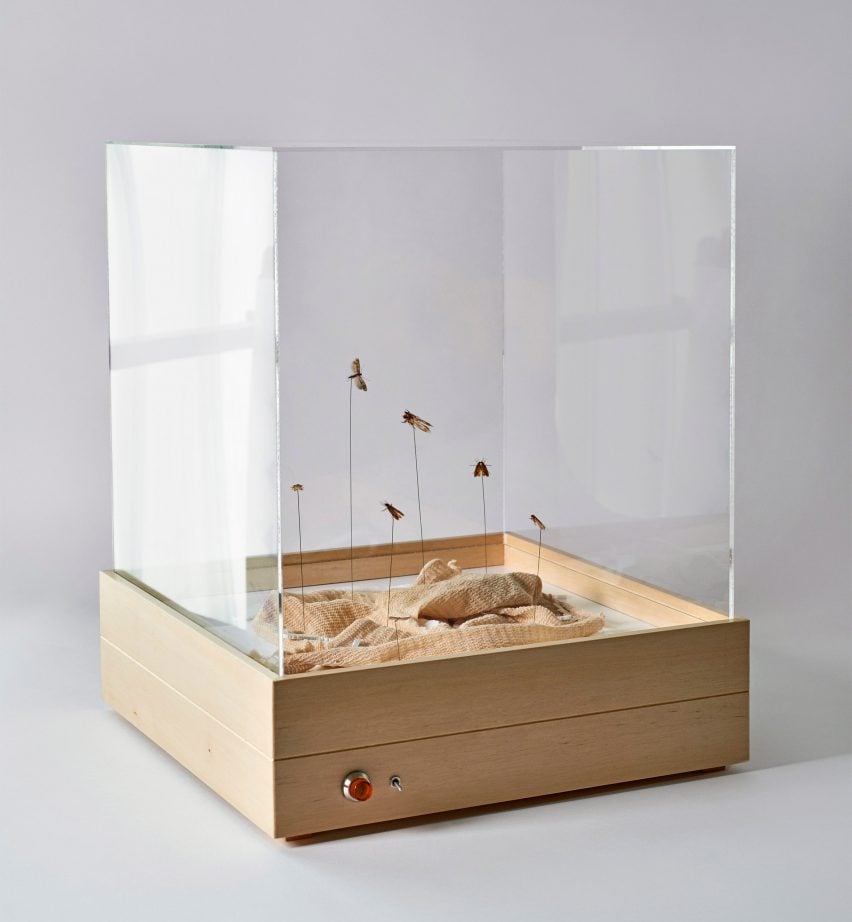

Pisapia initially proposed using common clothes moths to remove animal fibres from clothes, leaving behind the synthetic fibres so these can be recycled separately.

The moths feed exclusively on natural materials such as wool, fur, silk, felt and leather, as these contain a fibrous protein called keratin that their larvae can digest.

"I just thought that if clothes moths eat the beloved woollen clothes in our closet, why shouldn't they eat those we don't use anymore that have keratin inside," the designer added.

Pisapia developed the Made by Moths project during her final-year studies on the MA Material Futures course at Central Saint Martins art school in London.

The London-based Italian designer worked with experts from the Center for Novel Agricultural Products (CNAP) at the University of York to explore the potential for farming the moths' larvae and using them to digest the keratin-based fibres.

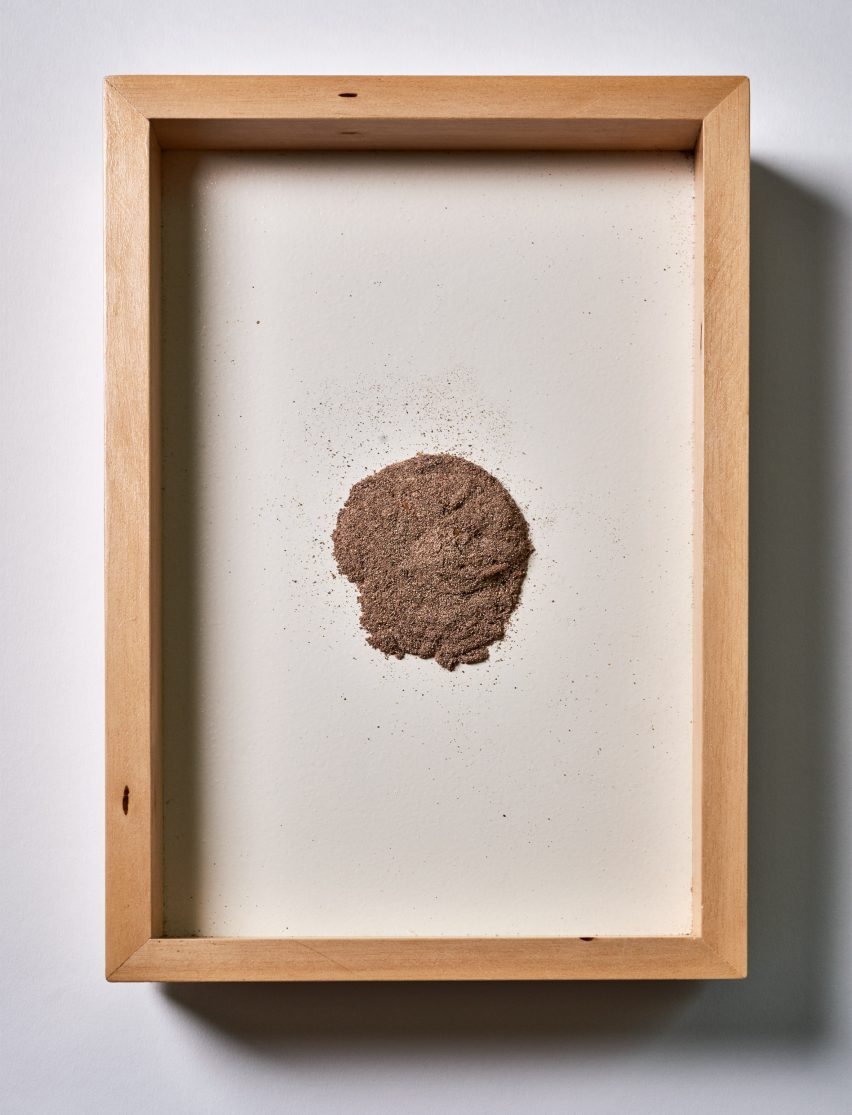

The dust-like waste produced by the larvae is entirely natural and will biodegrade over time. It can therefore be composted and will give something back to the environment rather than polluting it.

Pisapia said she views the bio-waste as "a precious material" due to the number of larvae and the time required to produce even a tiny amount of material. For this reason, she chose to celebrate its properties by transforming it into jewellery.

"I liked the idea that a brooch is something that goes on garments where the material comes from," she pointed out, "and also because a brooch can be used to hide or to highlight a hole that moths might have made in a garment."

The length of time it takes for the larvae to break down even small quantities of fibres prompted the team to explore alternatives, including the potential for extracting the digestive enzymes of the larvae and reproducing them as a bacteria that could perform the same task.

The result of this process would likely be an amino acid that could have alternative applications to the bio-waste produced by the larvae.

According to the designer, the process would take place initially in a laboratory, with the potential to upscale it to an industrial level.

"To manage this successfully would require a strong collaboration between designers, biologists, chemists and investors," she claimed.

Pisapia is continuing to speak with her collaborators at CNAP about the potential to develop the project and hopes to obtain funding to expand her research into the use of the moths' enzymes to improve the textile recycling process.

Tech-based clothing startup Vollebak also developed fashion that becomes insect food. The company used wood pulp and algae to make a t-shirt that breaks down in soil or in a composter within three months.