Architecture is overdue its own sexual revolution say Cruising Pavilion curators

Architects should embrace ideas of cruising and sex in public places in their designs, say the curators of an exhibition at ArkDes in Stockholm.

Cruising – the practice of looking for casual and anonymous sex in semi-public places – can be relevant to architecture if architects can be less squeamish about it, said Pierre-Alexandre Mateos, Rasmus Myrup, Octave Perrault and Charles Teyssou, the curators of Cruising Pavilion: Architecture, Gay sex and Cruising Culture.

"It's very enriching for architecture. Cruising is one aspect of a much larger sexual architectural revolution that needs to happen," Perrault told Dezeen.

"Sex, sexuality, desire and gender remains very untapped in the architectural discourse."

The curators told Dezeen that an injection of sex is a much needed dimension in architecture as societal attitudes to sexuality and gender evolves.

"Architecture must be sensitive to these societal evolutions and must respond to it with architectural proposals," added Perrault.

Exploring urban typologies that have been adopted for cruising could also inform designing cities and spaces that are more democratic, and accessible for queer women and non-binary people.

"We really wanted to expand on the idea of what lesbian cruising looks like, or what is it to be a non-binary person wanting to cruise," Myrup said.

Cruising a thermometer for urban health

Through architectural plans, artworks and speculative and conceptual projects, the exhibition explores how cruising embraces architectural space in the city and examines its role in fostering a sense of democracy in urban places.

"Cruising is a really accurate thermometer of a city being democratic," Teyssou said.

The Cruising Pavilion curators argue that cities must foster meetings between people across all genders as well as social, racial and economic backgrounds and that sexual encounters between people from all walks of life must be considered as well.

"A city that is not able to foster new ways and radical ways of having sex, is a city which is obsolete," Teyssou added.

Cruising necessitates space

Historically cruising has found its way into forgotten and transitional urban spaces such as alleyways, public parks and restrooms but can also happen in specifically designed spaces such as bath houses, bars, dark rooms, sex clubs and, in recent times, online.

"At its root cruising is an architectural practice. It necessitates space. You can't suck someone off if they're not in the same room as you," Myrup said.

The curators argue that cruising happens in spaces that have little to no architectural consideration as they are often out of sight to the public.

"A really interesting thing happens when you start to investigate the kind of design that does somehow happen anyway, either in purposely built spaces or the serendipitous design."

The design elements of cruising spaces

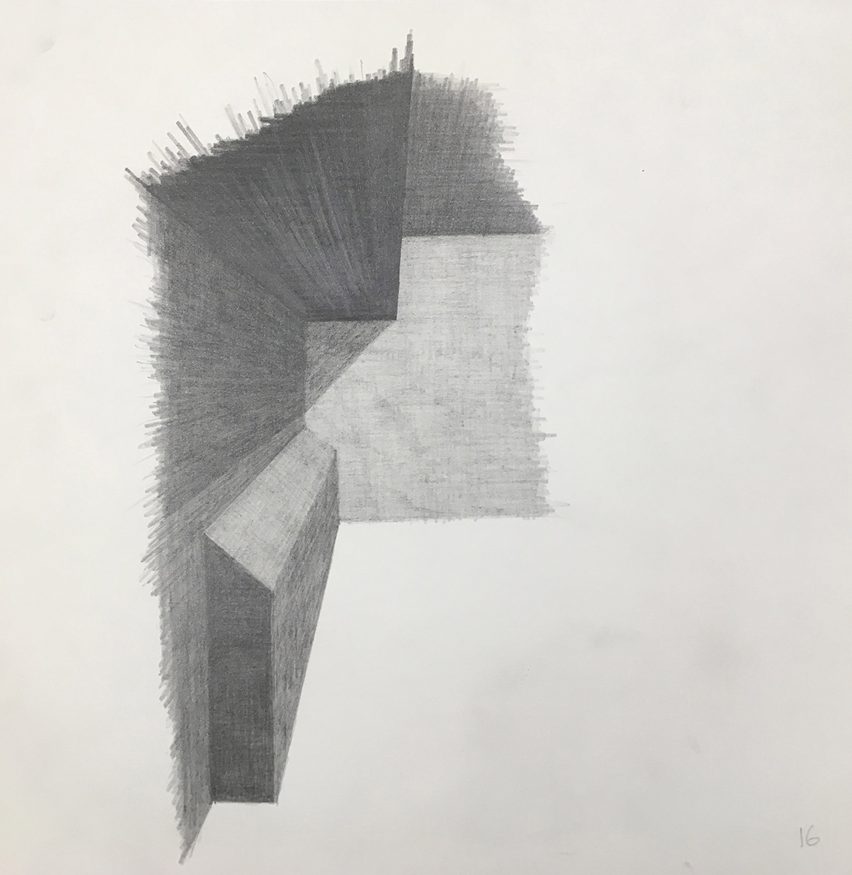

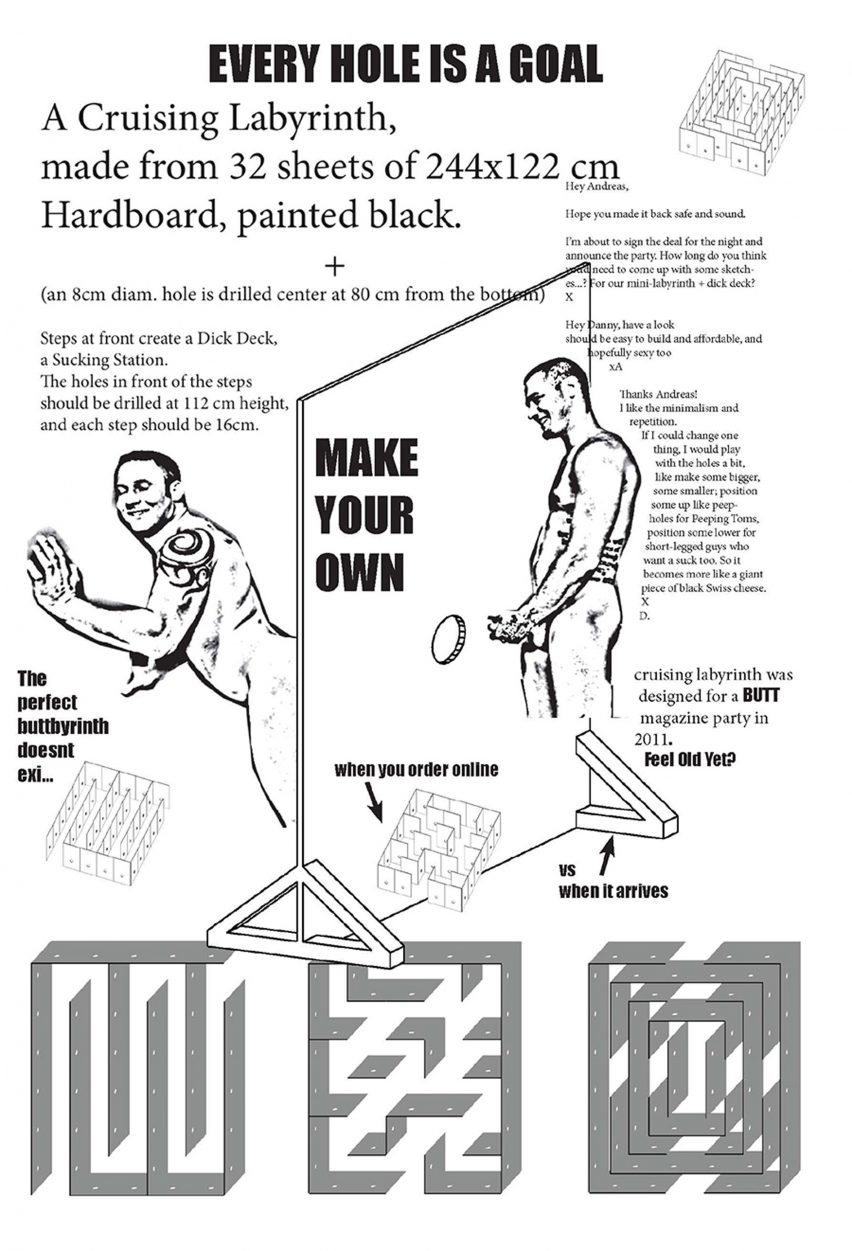

Spaces intended for cruising frequently adopt architectural features such as labyrinths, nooks, recesses to cater for hiding places and chance encounters.

"The darkroom is a rather recent architectural invention," said Perrault. "It uses several anti-modernist spatial strategies. It embraces the labyrinth, the maze and darkness as an architectural device which is precisely what has been eradicated for the last 300 years by all sorts of architecture whether public or private."

On show in the exhibition is the work of architect John Lindell including architectural features to be used in sex clubs such as a waist-height bench at a 45-degree angle that allows the user to "hang out without hanging out too much" as well as a recessed wall that allows the user to observe passersby without being seen.

"There is kind of a users manual of the cruising language," Myrup said.

"I think architects are interested in it but I think the people who commission buildings wouldn't want anyone to be able to loiter. So that's also why this language is kind of lost in architectural discourse."

Rethinking what cruising architecture could be

Recently cruising spaces and queer spaces in general have fallen victim to urbanisation and large scale development, particularly in London at the rate of 58 per cent in just 10 years.

However, Myrup argues that the shutdown of cruising spaces first began during the AIDS crisis.

"The AIDS crisis really impacted the architecture of cruising because a lot of places were closed down, with an excuse of doing it for the good of everybody," he said.

"But what we've seen is that no matter how hard people try to prevent cruising, no matter how many times they renovate parks or kick the gays out, people will suck dicks for eternity. So it's a very resistant and timeless venture."

Myrup also argues that cruising architecture may become more commonplace as attitudes to casual sex shift due to the normalisation of PrEP, a preventative drug which can stop an individual from contracting HIV after exposure.

"Perhaps there is room for a new kind of rethinking of what sexual cruising architecture could be and should be," he said.

New forms of cruising spaces

Although the term cruising is historically and culturally linked to gay men, the group argues that the practice transcends sexuality and gender.

"We really wanted to expand on the idea of what lesbian cruising looks like? Or what is it to be a non-binary person wanting to cruise?" Myrup said.

As cruising often adopts street-like and derelict architectural spaces, it's necessary to formulate the architectural vernacular of what cruising spaces for a breadth of genders and sexualities might look like.

"We showed a project by Maud Escudié and one of her points was that for her safety is more sexy than the kind of danger that is designed for gay male cruising," Myrup explained.

"For a woman, public space is often a space of danger," Teyssou added. "Walking alone at night in a city is not something arousing to a lot of women"

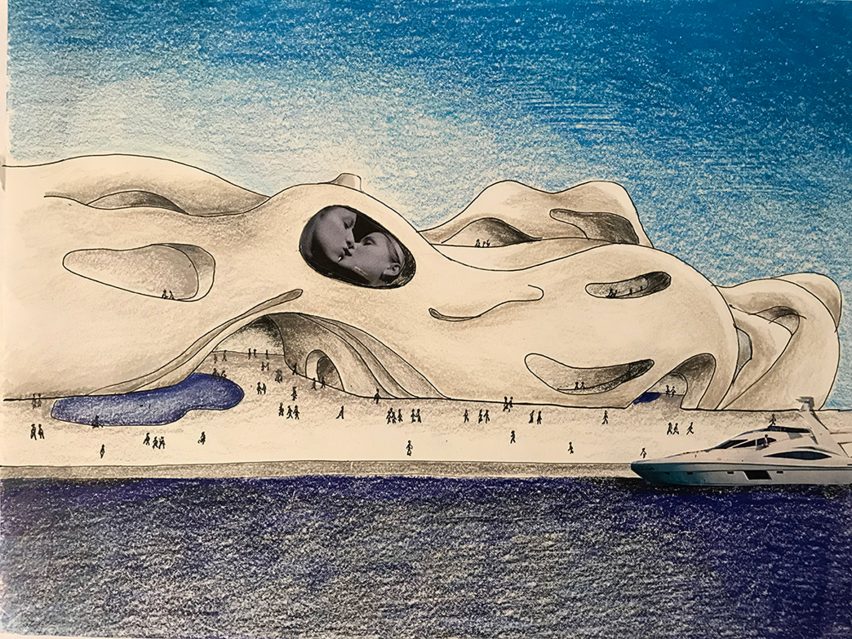

On show at the exhibition are several projects that speculate on what such cruising spaces might look like such as a project by Ann Krsul, Amy Cappellazzo, Alexis Roworth and Sarah Drake called Lesbian Xanadu, a "sexual mall for lesbians" that uses water as an architectural feature.

Another project on show is SHUI by Jon Wang and Sean Roland, who despasigned a bath house in Manhattan's China town meant for queer and non-binary people.

This is the third and final exhibition exploring cruising and architecture organised by the four curators. The first exhibition was held at Spazio Punch during the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale and the second was held at the Goethe Institute in New York.

Cruising Pavilion: Architecture, Gay Sex and Cruising Culture is on at ArkDes in Stockholm until 10 November.

Images courtesy of Johan Dehlin, Peter Hansen and Frida Vega Salomonsson.

Read on for an edited transcript of the interview:

Sebastian Jordahn: How would you define Cruising Pavilion?

Rasmus Myrup: I guess we call it a curatorial project. Is that the latest definition?

Pierre-Alexandre Mateos: A sexual think tank.

Rasmus Myrup: The four of us came together to resolve and investigate ideas of architecture, gay sex and cruising.

Sebastian Jordahn: Why did you decide to investigate cruising in relation to architecture?

Rasmus Myrup: The real moment when it clicked was when we discussed doing an exhibition at the Venice Architecture Biennale. At its root cruising is an architectural practice. It necessitates space. You can't suck someone off if they're not in the same room. And so there is a real necessity for space. The influences beyond that still come from this root of architecture. So that's very much why we hinged it on architecture. That's also why it made perfect sense with the Architecture Biennale because it is a forum where people go expecting something that works with spatiality.

Pierre-Alexandre Mateos: It seems that no one has more intimate relationship to space and the city experience than young homosexuals who cruise. Cruising is basically what you do when you arrive in a big city. You start to explore a territory to find a partners in a very physical part of the city. So you develop a really intimate relationship with space and architecture in it in that sense.

Octave Perrault: There's also a lack of discourse in this subject, much less than in art, and it seemed very rich to approach it from this angle. Because there is a lot of things to say.

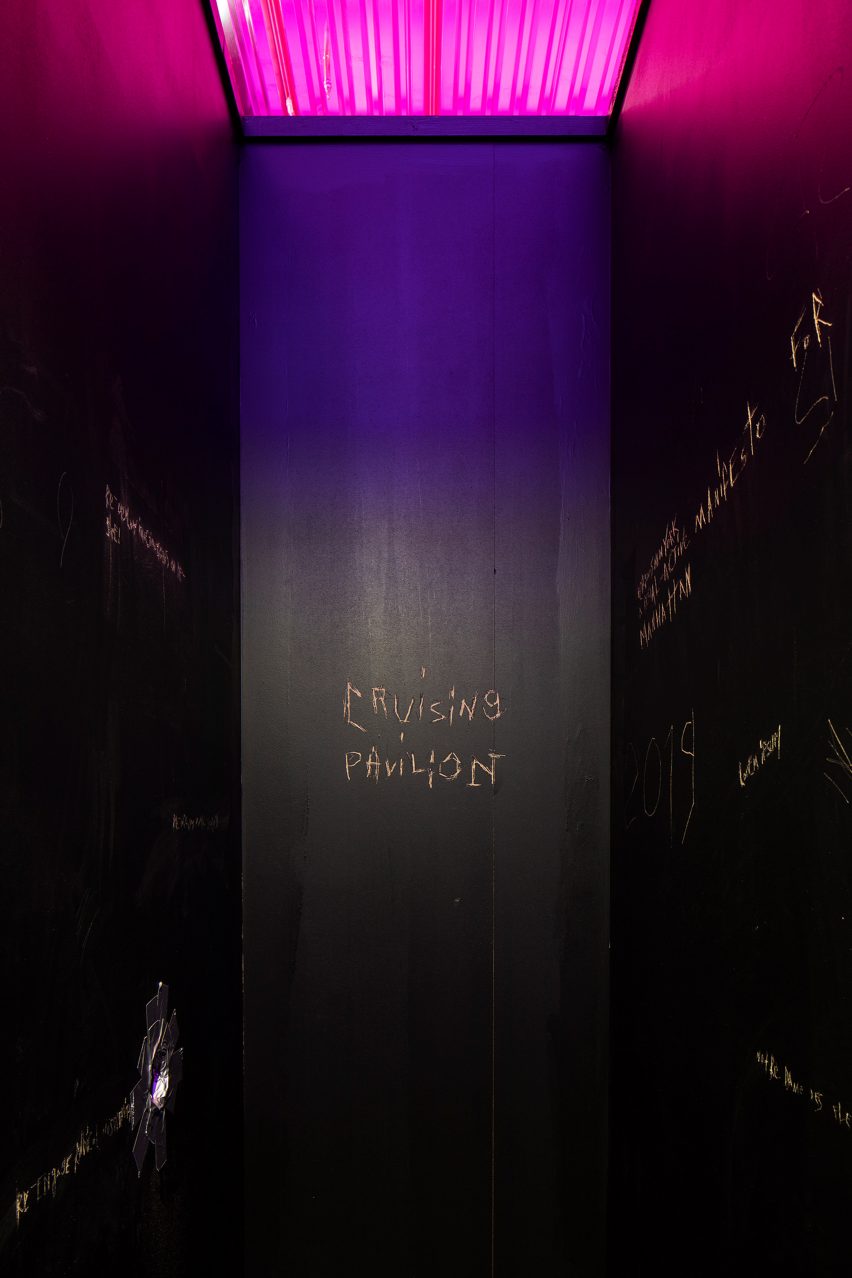

Sebastian Jordahn: Tell me about the exhibition at Ark Des.

Octave Perrault: It's the third edition of the Cruising Pavilion, which we consider to be the last edition of this exhibition series. It’s also the first exhibition we’ve done in a proper museum, or an institution. The first one was held during the Venice Architecture Biennale and was hosted at Spazio Punch. The second one was held at the Goethe Institute in New York. So one third of the Ark Des exhibition are the works from the first exhibition, one third are from the second exhibition and one third are new works.One of the challenges was to bring the topic to a museum and to articulate it to an audience that might not have any idea about the topic and to put it into form, into words and also to invest in the space, which is a large white cube. This was a challenge because the cruising spaces we investigated are very much anti-white cube. They are dark, small and labyrinth-like and we wanted to bring that kind of quality to the space.

Sebastian Jordahn: What’s different with this third iteration of Cruising Pavilion?

Pierre-Alexandre Mateos: The first one concentrated on a fetishised concept of cruising. The second exhibition tried to develop a site specific and clubby atmosphere linked to New York's history, and extended the investigation to include different identities, politics and a different subjectivity. The last one was more articulate. We tried to fulfil the gap between the first and the second exhibition so went from the bar, to the history of dark rooms and sex clubs, to a more cybernetic new media aspect of cruising.

Octave Perrault: One of the attempts we made was to formalise the importance of domestic space and cyberspace in cruising. We remain quite ambiguous on this but we investigated the contemporary edge of cruising that is facilitated by apps like Grindr.

Sebastian Jordahn: It seems the exhibition is split up into the bar, the dark room and a bedroom. Why did you split it up like this?

Pierre-Alexandre Mateos: We started with the bar because it is kind of an extension of cruising spaces. Then the second space was a dark room. We wanted to emphasise how the dark room was a space of politicisation for a lot of people during the AIDS era. There was kind of a cold sex war during the 80’s with mayors of cities shutting down sex clubs in order to reduce the impact of AIDS. The last space, the bed room, explores how cruising has been liberated in a way and how geo-social apps have challenged cruising. These apps are super interesting tools for solidarity and networking but it can be used to track and survey also.

Rasmus Myrup: This triad in this philosophy is by no means us trying to make an extensive presentation of what cruising is. There’s so many more places where cruising happens, but we just wanted to focus on those three types of interior spaces for the show.

Sebastian Jordahn: How could these spaces be considered architecturally?

Octave Perrault: The darkroom is a rather recent architectural invention. It seems to have really developed after the war in a very postmodern manner. It uses several anti-modernist spatial strategies. It embraces the labyrinth, the maze and darkness as an architectural device which is precisely what has been eradicated for the last 300 years by all sorts of architecture whether public or private. But this one has resisted through the ages.

Pierre-Alexandre Mateos: Cruising has invented its own grammar or its own vernacular. There is a tension between modernism and ornament. Cruising spots, at least in sex clubs, often pretends to be rough and brutal and expands the industrial aesthetic of the street, when in fact is full of ornaments imitating the street. This tension between the pure roughness and ornament is a really interesting point. And an interesting subject in architecture.

Rasmus Myrup: One theory could be that the schema found in the chaotic mediaeval city, like pre-Osmanian architecture for example, is also found in cruising spaces, because they do have these weird alleys and dark areas.

Sebastian Jordahn: How does cybernetics come into play?

Charles Teyssou: The birth of like the modern dark room was approximately around the 1950-1960s and it was the first time that forms of mass media like TV and porn became super popular. It was also the first time that drugs like poppers and drugs for sex were mass distributed. So dark rooms became an architecture with walls but also with porn and drugs. It was like the first kind of cybernetic sexual architecture in history. Cruising invented an avant-garde of cybernetic architecture even before Hans Hollein theorised around architecture being a pill. But corporate architecture or architecture with a capital A, will try to diminish the space where cruising can develop.

Rasmus Myrup:We found a very interesting justification in doing a project about cruising because of the intersection that is going on between digital cruising and let's call it old school cruising. Some people don't even think that using geo-social apps like Grindr is considered cruising. On the other hand a lot of people see it as a kind of mainstream education that is opening up for more people to be able to cruise. Cybernetics already played a part in the birth of the modern darkroom and now you're seeing cybernetics playing a big part in the in the current state of cruising and architecture.

Sebastian Jordahn: Does this research have a place in contemporary architecture?

Octave Perrault: Approaching contemporary architecture with cruising is very enriching for architecture discourse and maybe cruising is one aspect of a much larger sexual architectural revolution that needs to happen because sex, sexuality, desire and gender remains very untapped in the architectural discourse.

Sebastian Jordahn: How so?

Octave Perrault: Sexuality is very much absent or under considered in architecture. But then architecture is a particular art form involved with some of the most powerful and dominant forces. And therefore cruising and any deviant practices or sexual things are erased from the discourse of the architectural form. Actually architecture is mostly an act of ordering things in space, giving them position, giving them a name and a form. And anything queer basically resists that. So maybe there is a fundamental contradiction between the two.

Octave Perrault: Sexuality has been a particularly vivid political frontier in the last few years, devised more along gender lines rather than sexuality only. So by a sexual architectural revolution, I mean that architecture must be sensitive to these societal evolutions and must respond to it with architectural proposals. I see the Cruising Pavilion project as a contributor to this by bringing visibility and reference points. If anything, the project showed that there was a demand for more architectural production on these topics.

Rasmus Myrup: There's an interest intersection between architecture and cruising in that most cruising stereotypically happens in liminal and kind of forgotten spaces. In architecture, the body is pushed aside and edited out but you know people still want to have a blow job. So you go in the park when it's dark. So a park during the hours of night is kind of useless and no one is there. So that's why people go there to get a blow job and the same goes for truck stops and public toilets. A really interesting thing happens when you start to sort of investigate the kind of design that does somehow happen anyway, either in purposely built spaces or serendipitous cruising spaces.

Sebastian Jordahn: Do you find there are architects purposely using these design tactics?

Charles Teyssou: We found that a lot of official architects won't advertise or mention their projects related to cruising. When we contacted architects who have worked in this field, a lot of them were super surprised that we found them. We also found that there were a lot of projects and spaces that were super intricate architecturally speaking, but then no architect was officially connected to it. And so we had to dig into the web and archives in order to find who designed it. Most of them are not built by architects but interior designers, students or even owners of bars who build the spaces for their clients. So you have a lot of architects in the closet in many ways.

Rasmus Myrup: One of the points that Octave mentioned is that architecture has been trying to do the exact opposite for so long. Making big open spaces with no separations nowhere to hide, nowhere to do anything dubious. So I think we're finding it hard to answer like how people are utilising these tactics because they have basically been obliterated from the architectural discourse. We found this beautiful cruising space in Germany but none of us could find out who fucking drew it. Because the architect completely obliterated his or her name. But what we've seen is that no matter how hard people try to make cruising not happen, no matter how many times people renovated parks or kick the gays out, people will suck dicks for eternity. It's going to happen whether there's an architectural plan for it or not. So it's a very resistant and timeless venture.

Sebastian Jordahn: What are some other design tactics of cruising that you came across in your research?

Rasmus Myrup: One of the architects that we work with for the show in New York is called John Lindell. We found a kind of secret project that Lindell had deleted from his website but we found it in an old publications. He had these beautiful drawings that he had done of nooks and these places where you could stop and fall into a wall and observe, places where you could lean on a bench but not sit down, and all these architectural elements that he thought of when he was cruising back in pre-AIDS times even. We were actually able to build some of these architectural elements that he did. We built a butt bench, which is a butt height bench with a 45 degree angle so that you could kind of hang out without hanging out too much. We also build a wall with a recess with nothing inside. It was in this labyrinthine space where you could enter and not be seen from the sides but you could still observe people passing.

So there is a "users manual" of cruising language but I think it'sthe opposite of what people commissioning buildings want. I think architects are interested in it but the people who are commissioned buildings, they wouldn't want anyone to loiter or be able to hide from the observer. So that's also why this is lost in the architectural discourse.

Sebastian Jordahn: You said that cruising is a thermometer for metropolitan health, could you explain what you mean?

Charles Teyssou: It is from this iconic book by this American writer called Samuel R Delaney about cruising called Times Square Red, Times Square Blue that he wrote in the 1980s or 1990s about cruising in Times Square. Times Square was like a sexual babylon where a person's social, cultural, economic background didn't matter. Here cruising was like a democratic hub that was breaking the social hierarchies normally present in real life. We extended on that argument to say that a city that is not able to foster cruising or new and radical ways of having sex, is a city which is obsolete. Obsolete in terms of not being able to produce new types of relationships between different type of people. It's just a city in that it fixes and solidifies position instead of building up ambiguity, public spaces and new meetings. So in that sense cruising is a really accurate thermometer of a city being democratic.

Sebastian Jordahn: How do you think urbanism has impacted cruising spaces?

Rasmus Myrup: The AIDS crisis gave a lot of leeway for policymakers to wipe away a lot of old cruising cultures for instance, cottaging. It was very heavy handedly wiped out under the guise of being "for the good of the people". For the exhibition at Ark Des we also tried to root the exhibition research in Sweden and actually Sweden was the only country in Europe to completely ban any venue establishment encouraging sexual encounters during the AIDS crisis. In general the AIDS crisis really impacted the architecture of cruising because a lot of places were closed down. And now that we see this kind of Prep-filled future and a return to pre-AIDS behaviour, perhaps there is room for a new kind of rethinking of what sexual cruising architecture could be and should be.

Sebastian Jordahn: Cruising is of course mostly known as a gay male practice but are there spaces for other gender identities and sexual orientations?

Rasmus Myrup: That's very much what we tried to work with in the second iteration of Cruising Pavilion. We expanded on the idea that cruising is not just a dude in a leather jacket looking for another dude in a leather jacket and a beard, you know? What does lesbian cruising look like? Or what does it mean to be a non binary person wanting to cruise? In the show in Stockholm, we included the project S H U I by Jon Wang and Sean Roland. They designed this very open space with a lot of glass separation. The space uses steam and moisture to kind of obscure things and it's meant to be a space for non-binary cruising, or people who are either gender non-binary or sexually fluid.

We also showed a great project by Ann Krsul, Amy Cappellazzo, Alexis Roworth and Sarah Drake called Lesbian Xanadu, which was a kind of sexual mall for lesbians.

Charles Teyssou: It was a theoretical project that was never meant to be realised. In the manifesto, they were saying "we want to fuck like gay men, we want to fuck without having children, we want to fuck without being obliged to have emotional bonds”. The main architectural material was water. Everything architecturally speaking, was a metaphor for water. For example the entrance is a massive waterfall. When we spoke with another lesbian architect they were saying "dark rooms wouldn't be a sexual trigger for us" because a dark room is supposed to mimic a city at night. And basically, for women, walking alone at night in a city is not like something arousing. The anonymous aspect of being alone is not a sexual trigger. Because for a woman public space is often a space of danger.

Rasmus Myrup: We also showed a project by one of our good friends Escudié. One of her points was that for her, safety is more sexy than the kind of danger that is designed for gay male cruising. She said that being behind a locked door in a cabin, in a dark Labyrinth, somewhere in the corner, where no one can hear you scream, is not sexy. She would want to always be able to escape. She said that if cruising could be like hide and seek in a room full of flowy fabrics that would be much better. Because you could still hide but someone can always find you and someone can always be next to you. And you feel a little more safe and warm inside.

Sebastian Jordahn: What’s next for cruising pavilion?

>Rasmus Myrup: From the beginning we always saw Cruising Pavilion as a project where we would investigate the connections between cruising and architecture. And with these three exhibitions, we feel that we have done that and achieved what we wanted. So we see this exhibition as the last but we will follow up on all the research.