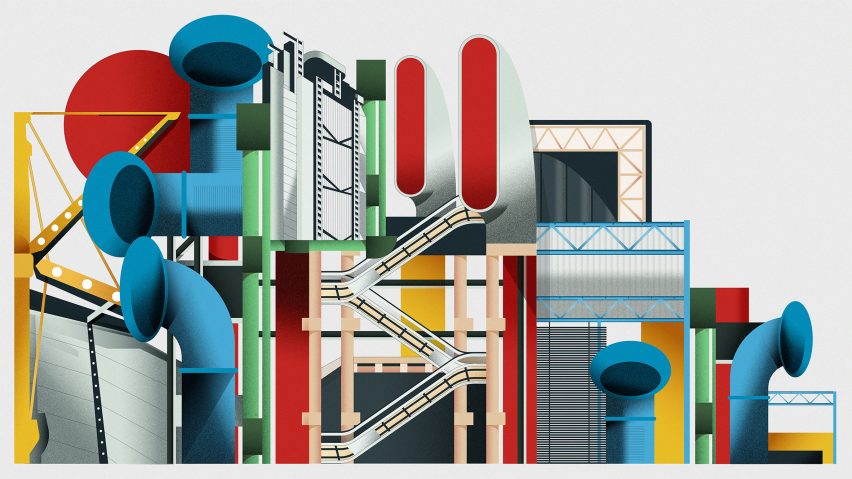

High-tech was the last major architecture style of the 20th century. This overview by Owen Hopkins kicks off our series exploring the high-tech movement.

In 1971, a press conference was held at the Élysée Palace to announce the winners of the competition to design a new multidisciplinary arts centre on Paris' vacant Plateau Beaubourg.

On one side stood the immaculately besuited figure of President Georges Pompidou, on the other were the architects: long-haired and dressed rather more casually in tweeds, denim and tie-dye. One of their number even had a beard.

The winning scheme being presented by the architects, Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, then both in their thirties, was even more radical than their appearance. Their design envisioned a vast steel frame, adorned on the outside by lifts, escalators and ventilation ducts, leaving the interior spaces completely open and adaptable.

Piano and Rogers' proposal had beaten 680 other competition entries, but even more remarkably it was actually built, going on to become one of the great buildings of the final decades of the 20th century and embody many of the ideals of high-tech architecture.

The contrasting group of characters standing before the journalists must have been a strange sight. Yet, in a funny way it was entirely fitting, prefiguring how the building would end up symbolising an uneasy alliance between the establishment and 1960s radical culture – an alliance which in a roundabout way has come to define what has become known as high-tech architecture.

Today, the balance of that alliance appears to have shifted decisively in favour of the establishment, as high-tech and its descendants have morphed into a kind of corporate modernism.

One of the great ironies of high-tech was that its signature wide-span open spaces were particularly suited to financial trading floors.

Although high-tech's latter-day corporate manifestations are a world away from the Pompidou, this was always the risk for a movement in which flexibility and adaptability were so integral. And for all of high-tech's vigour and sense of purpose, there remains something about its exaggerated, almost mannered radicalism that suggests somewhere deep down its architects knew that modernism's time was nearly up.

High-tech origins go back to the high point of post-war modernism. And as a child of 1960s radical culture, it has several parents. Firstly, there was Archigram, the avant-garde group of architects based at London's Architectural Association in the 1960s known for their seductive, graphic design and pop culture-inspired imagery.

Fascinated by everything from space travel and sci-fi, to consumerism, mass culture and aspects of Victorian engineering and industrial design, Archigram created captivating visions of futuristic cities.

Among them Peter Cook's Plug-in City, which imagined vast megastructures where individual elements could be added and subtracted as technology and requirements progressed – an idea that carried over directly into high-tech and similarly went unrealised.

Archigram's ideas assumed a future of abundant energy and resources. At the other end of the technological spectrum were Buckminster Fuller and Frei Otto who explored what could be achieved through an economy of materials, particularly via tensile structures – which became another familiar feature of high-tech architecture. Then, there was Louis Kahn's idea of "served" and "servant" spaces, which proved highly on high-tech architects' separation of spaces of use from circulation and service spaces.

Finally, there were the ways advanced technology might be aligned to radical social programmes, and in particular the ideas of architect-thinker, Cedric Price. Particularly influential was Price and theatre director Joan Littlewood's 1961 project for a Fun Palace, conceived as a new kind of community cultural space which blurred conventional notions of performance and participation.

Rejecting the monumentality of traditional cultural institutions, Price envisaged the building as a moveable and adaptable framework geared towards the promoting of new social and cultural interactions.

The Centre Pompidou clearly owed a lot to the Fun Palace, and in many ways would have been inconceivable without it. That it got built, and the Fun Palace did not, was due to the architects' willingness to adapt their radical ideas to serve practical, real-world uses, and also the pivotal contributions of the engineer, Peter Rice, a vital and sometimes overlooked figure in the high-tech movement.

Inevitably, the first high-tech projects were modest and small-scale. A good example was the Reliance Controls Factory in Swindon by Team 4 – the short-lived practice formed in 1963 by Su Brumwell, Wendy Cheesman, Norman Foster and Richard Rogers.

Completed in 1967, the building comprised a radically stripped-back rectilinear frame, thin diagonal tie-beams and corrugated steel facing – a response to the brief's stipulation for economy and speed of construction.

Arguably even more radical than the overtly industrial structure was the building's lack of separation between managers and shop floor, in favour of a highly flexible, nonhierarchical space – again prefiguring ideas that found later form in Rogers' work at the Pompidou and following buildings.

Team 4 split the same year Reliance Controls was completed: with Rogers and Brumwell setting up a studio, and Foster and Cheesman, who had married in 1964, founding Foster Associates. In 1971, they were appointed to design a new headquarters for the insurance company Willis Faber & Dumas in the East Anglian town of Ipswich.

The resultant building offered a rather different interpretation of high-tech ideas than the inside-out approach.

Instead of abruptly confronting its surroundings as an inside-out building would inevitably have done, the Fosters pushed the technology of the day to its limits to create a gossamer-like glass curtain wall that gently curves its way around the building's perimeter. By day, it reflects the town onto itself and by night, it becomes almost invisible, dramatically lifting the veil on the company's activities within.

Inside, the building features innovative open-plan office spaces, and amenities like a swimming pool and roof-top restaurant and garden, which, together with its exemplary energy performance, showed what high-tech could offer the enlightened corporate client.

The Centre Pompidou had brought high-tech to international attention, but it was the Willis building that signalled the direction the movement would take over the next decade. In 1986, high-tech reached what in retrospect was probably its high point, with the completion of Rogers' Lloyd's building in the City of London, and Foster's Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporations headquarters in Hong Kong.

Both buildings, albeit in quite different and distinct ways, showed in dramatic fashion how externalising a building's structure and services, again made possible by cutting-edge engineering, could allow the creation of uniquely flexible – and thrilling – internal spaces that encouraged interaction among workers, while at the same time make powerful and lasting contributions to cities as different as Hong Kong and London.

High-tech is indelibly associated with the parallel careers of Rogers and Foster, but others associated with the movement created their own variations and took it in different directions.

The work of Nicholas Grimshaw began and has remained more avowedly modernist in its principles, whether in the stripped back Financial Times printworks in east London in 1988, the overtly functionalist Sainsbury's supermarket in Camden, also in 1988, or the neo-futurist geodesic domes of the Eden Project in Cornwall, completed in 2001.

Meanwhile, the partnership of Michael and Patty Hopkins, after creating their own space-age home and the Schlumberger Research Centre in Cambridge in 1985, showed how high-tech could work in historic settings, from Lord's Cricket Ground in 1987 and the Glyndebourne Opera House in Sussex in 1994 to Portcullis House, opposite the Houses of Parliament in 2000.

The assimilation of Portcullis House into such an historically sensitive location is a remarkable transformation for a movement that, despite its proponents' admiration for Victorian industrial architecture, has frequently attracted criticism for its often uncompromising aesthetics.

Few buildings attracted the vitriol aimed at the Lloyd's building upon its completion. Yet in retrospect its appearance could not have been more fitting: an office building adopting the aesthetic of industry at the very moment of the UK's shift from industrial to a financial services-based, post-industrial economy – of which a slick, corporatised form of high-tech would become one of the defining aesthetics.

Despite this fate, there is still much that the movement's early ideas can offer our present moment. As technology comes to dominate every facet of our lives and social interactions, the best high-tech buildings offer a clear vision of its emancipatory power, of how deeply held social and democratic values can and should inform its use, so that technology is harnessed for the benefit of everyone.

When in 1966 Cedric Price asked: "Technology is the answer, but what was the question?", Rogers answered him indirectly only a few years later with his belief that the Pompidou must be "a place for all people". Over four decades later, it's an answer that remains as important as ever.

Illustration is by Jack Bedford.