In the wake of recent controversies surrounding the funding of major institutions – dubbed "toxic philanthropy" – we must rethink the system for supporting culture, says Forensic Architecture researcher Robert Trafford.

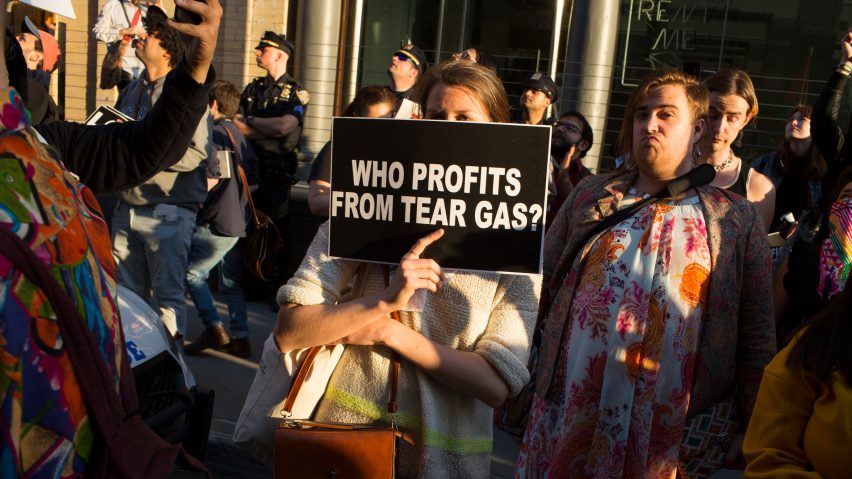

When the 2019 Whitney Biennial drew to a close in September, the show had lived up to its reputation as unfailingly controversial. A storm that began at the Tijuana-San Diego border swept through New York, forcing Warren B Kanders, owner of a leading tear-gas manufacturer, to resign his position on the Whitney's board.

We are in an inclement season for philanthropy; a separate storm recently engulfed MIT's Media Lab, precipitating the resignation of director Joichi Ito over the alleged hidden extent of the institute's relationships with Jeffrey Epstein. In London, leading theatres are backing away from fossil fuel money. The Sackler Foundation has put away its tainted chequebook altogether. In the aftermath of these controversies, there is an opportunity to take the first steps on a difficult road.

It will have to start with an admission: the traditional model of philanthropic support, which makes our foremost institutions of innovation, heritage, and cultural memory dependent on extractive capital, is an ongoing act of self-harm. We must not miss the opportunity to explore how we can reduce the dependence, and replace the model. And while individual practitioners can drive this change, there is a defining role waiting to be played by an institution that is brave enough.

In the aftermath of these controversies, there is an opportunity to take the first steps on a difficult road

In late 2018, amid growing controversy, it wasn't an easy decision for Forensic Architecture to accept our invitation to the Whitney Biennial. Exhibiting in such prestigious spaces can drive our cases forward, and we have previously understood this as a trade-off: a step into the imperfect politics of the art world, justified by an amplifying effect on the stories at the heart of our investigations.

We understood that there is no truly pure position; museums and universities are vaults of symbolic capital, and in entering into them, practitioners become entangled in the value exchange by which the reputations of profiteers such as Kanders are laundered. We resolved to participate only if we could attempt to invert this economy.

Everything that led to Kanders' resignation underscores the resurgence and diversity of the movement to decolonise our institutions, and to reimagine them as sites of restitution, equality and dignity. Those institutions should embrace and nurture this movement, not resist it.

Instead, the cultural establishment is stalling for time, either bankrupt of ideas or pretending to be. They "cannot right all the ills of an unjust world", said Adam Weinberg, the Whitney's director. Indeed, nobody is asking them to, and this kind of misreading of what is being asked is pervasive, and feels disingenuous. The Ford Foundation chief Darren Walker recently gave us another example.

After Kanders' resigned, Walker said all the right things, arguing for more diverse museum boards and forward-looking institutions that support "the exhilarating work of building community". But how far does this attitude really extend? One doesn't get the sense that Walker is deeply interested in listening to those with whom that community-building needs to start.

"We don't need to demonise wealthy people", he later told ArtNet's editor-in-chief, Andrew Goldstein, on the subject of Kanders. "We've lost our ability to understand nuance." Goldstein, in the same piece, writes that Walker "better than most, understands how reliant culture is upon private philanthropy".

It barely needs outlining how abjectly these statements fail to read the room. Kanders was not "demonised" because he is wealthy. Kanders' association with the Whitney was considered objectionable because, simply, it was the result of a business model which people consider to be built on violence and injury.

To argue that culture owes its existence to philanthropy draws walls around what we mean by culture at all

The Whitney's own staff wrote that the communities against whom Safariland's tear gas has reportedly been used – in Standing Rock, Ferguson, Tijuana – are "our communities". Activists from Puerto Rico picketed the Whitney even as Safariland's tear gas was reportedly being used against protesters in the territory. A broad cross-section of artists and theorists implored the museum not to "provide cover for the likes of Kanders as they profit from war, state violence, displacement".

To be contemptful of our institutions when they serve as reputational rehab for the beneficiaries of a militarised police state is not, as Walker suggests, an "extreme perspective". To dismiss it as such, while lamenting an absence of nuance in the debate, says everything about the privileged position from which Walker can speak without listening. If not the museum's staff, artists, critics, or visitors, who exactly does he expect to do this work of "building community" with?

Similarly, to argue that culture owes its existence to philanthropy draws walls around what we mean by culture at all, erasing and belittling what is outside. How can this not be understood as another violent act? Nicholas Galanin, one of this year's Biennial exhibitors, wrote powerfully about the museum's "self-congratulatory climate of comfort for the existence of economic disparity, cultural suppression, erased histories, and white guilt". This is the culture that the support of profiteers and abusers perpetuates.

Walker et al are trying to have it both ways. Of course, we're told institutions and their boards should be more reflective of, and receptive to, the communities they proudly serve. But when those communities happen to take issue with a particular individual, we're told that the system is imperfect. Of course it is, but it's the only system that's possible; to blame any individual for that unfortunate fact is nonsensical, uncivil, extreme.

This arrangement survives only by insisting on the inevitability of its own logic: last month, Nicholas Negroponte, one of the Media Lab's founders, reportedly told a staff meeting that he would "take the money" from Epstein all over again. But that insistence is hollow, and its time is up.

It's true that it is not easy to articulate what a changed system looks like. Undoubtedly, institutions enmeshed in the existing model have a hard road ahead, and we can empathise with this; much of the world is, after all, deeply entangled in structures which are slowly burying us.

But for exactly that reason, this process of working out how to support innovation, solidarity, and expression without relying on crumbs from the table of extractive, violent economies is good for us all. It has the potential to place our institutions back at the heart of our shared growth, to restore them as spaces of struggle and solidarity. It is precisely the common cultural project that we should be engaged in, and it is exactly the "exhilarating work of building community" that our institutions are invited to begin. Every controversy, every protest, every Kanders is another invitation.

Don't step down – step up

A year ago, Whitney staff demanded "a clear policy around Trustee participation"; it is high time that the museum responded publicly to this demand. Among our fellow exhibitors, discussions around "nonviolent, sustainable giving" have begun: foster these discussions, engage with them. Take ownership of previous mistakes, admit them but grow out of them ("don't step down – step up", as a Media Lab staffer put it to me). Engage with the powerful collective that is rising outside of the art world's conflicted logics. Reexamine the existing system of tax breaks for donors, which gives credit to individuals for what is, in essence, a vast public subsidy.

The Whitney and the Media Lab have each been presented with a singular opportunity to lead; to show that they can meaningfully critique the structures that threaten the integrity of their artists and researchers. A political and social moment has arrived – quite literally and physically – at the gates of our centres of culture and innovation. The smart ones will rise to meet that moment, and work out what the institutions of the future are going to look like, together with the people and communities they're supposed to look like, but never have.

Featured image is by Andrew Lichtenstein, courtesy of Getty Images.