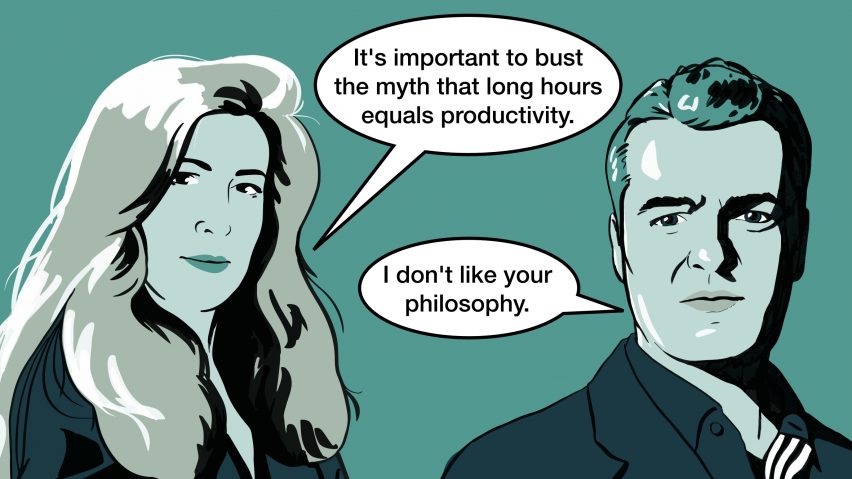

Patrik Schumacher and Harriet Harriss clash over long-hours culture at Dezeen Day

Patrik Schumacher defended architecture's long-hours culture at Dezeen Day last week, arguing that protecting students from working too hard could lead to a "socialist kind of world of stagnation".

Schumacher, the principal of Zaha Hadid Architects, spoke on a panel about design education, claiming that worrying about exploitation of workers could have a "paralysing" effect on companies like his.

"In my world, talk about protecting students from working too hard, from late-night working in firms like ours, that's the wrong story," he said.

"This is a competitive place where people are eager, have passionate and want to succeed and want to do something," he added. "But you can't do that if you're told that if work beyond eight hours you can observe exploitation, and something is wrong with you."

But Harriet Harriss, dean of New York's Pratt Institute School of Architecture, argued that working long hours leads to a decline in productivity and could trigger mental health problems.

"It's very important to just bust the myth here that longer hours equals productivity," she said.

"There's been goodness knows how many studies that have been identified that the UK is actually less productive than countries that have a limit [on working hours]."

"What we are doing, arguably, is making permissible forms of labour exploitation"

The panel discussion, titled fixing education, brought together educators including school teacher Neil Pinder and young designer Stacie Woolsey as well as Schumacher and Harriss.

Harriss argued that schools should strive to promote healthy working practices rather than perpetuating the toxic long-hours culture that is common in architecture studios.

"Educators are asked to create a micro version of professional practice within universities. We mimic the long hours, we throw all-nighter demands of professional practice," said Harriss.

"What we are doing, arguably, is making permissible forms of labour exploitation, and creating work-life balance that often triggers mental health [issues]. And we know this is a pretty serious issue in education at the moment," she added.

"If we keep thinking it's about some sort of improvements to education translating into private practice, we're not really understanding that we need to work collectively to find meaningful solutions."

"I don't like your philosophy," retorted Schumacher, who is co-founder of the Design Research Laboratory unit at the Architectural Association.

"If you apply this to our work it means a slow down, a freezing up, paralysing. It's a kind of socialist world of stagnation and that's nearly what Europe has become."

"There needs to be some form of balance within the industry"

Moves to limit working hours will put European firms at a disadvantage, he argued.

"This will certainly not work and there will be others who push this forward," he said. "You look at China. China's an amazing engine for this and you feel the hunger and the eagerness and also all the firms starting up."

But Harriss dismissed this attitude as outdated. Arguments about long hours, she said, are part of the wider problems in architecture and design.

"There needs to be some form of balance within the industry," said Harriss. "It comes back to our biggest concern, this issue of access and affordability."

"I don't want anybody to work for less than the minimum wage"

Harriss and Schumacher spoke on the panel alongside Neil Pinder and Stacie Woolsey.

Long hours for students and graduates coupled with low wages makes a career in architecture or design hard to access, especially for BAME (Black, Asian and minority ethnic) students and those from low income backgrounds, argued Pinder, who is head of design at Graveney School in south London.

"I don't want anybody to work for less than the minimum wage," said Pinder, who won a Teacher of the Year award for his work introducing a new generation of BAME children and young people to architecture.

Young architects and designers should be able to afford housing and lunch in the cities they take apprenticeships in, Pinder added.

"Not being slave labour, [that's] what we're talking about when you're working for next to nothing."

To have a diverse industry we need to diversify education, said Woolsey

Lack of diversity in the design sector is bad for architecture too, Pinder said. "If you're not drawing on the community, this brilliant city, this brilliant diversity, then you're not going to be having the best architects, the best designers the best in terms of creativity that London has to give."

A more egalitarian approach to education and employment would improve the system for everyone, agreed Woolsey, a young designer who created her own Master's degree course when she couldn't afford the high fees charged by institutions.

"If you don't diversify education, how can you ever expect to have a diverse industry?" she added. "It cuts off the talent pool at the source."

Woolsey wanted to study a masters but said "it became very apparent very quickly that this wasn't going to be an option for me. I was quoted £40,000 to live and learn in London by a leading postgraduate institution."

"And so I decided, if I can't buy an education, how do I make one?"

Woolsey now aims to guide 10 students who have faced barriers to learning through her Make Your Own Masters scheme. She is now taking applications for 2020.

In a #dezeenchat on our Twitter and Instagram in July, Dezeen readers said that the stresses put upon them from architecture education led to burnout, mental health problems, and even thoughts of suicide.

Schumacher also took to social media to share his thoughts on education, warning that architecture academia is in crisis on his Facebook page. He warned that students could leave university without a portfolio containing "a single design that could meet minimal standards expected from a contemporary competition entry."

Dezeen columnist Sean Griffiths, a professor at the University of Westminster and former visiting professor at Yale University, responded with a defence of the current education system. "It is emphatically not the job of architecture education to mimic practice and generate workers for the profession in its present mode," he said.

The first ever Dezeen Day took place at BFI Southbank in London on 30 October 2019, in front of a sellout audience of 450 people.

Other panels at the conference included a discussion on how artificial intelligence will shape the way humans live in the cities of the future, and a debate on the place of plastic in the sustainable design movement.

Main illustration is by Rima Sabina Aouf, photos are by Mark Cocksedge.