Richard Rogers is high-tech's inside-out architect

We continue our high-tech architecture series with a profile of Richard Rogers, the architect of two of the movement's best-known inside-out buildings, Centre Pompidou and the Lloyd's building.

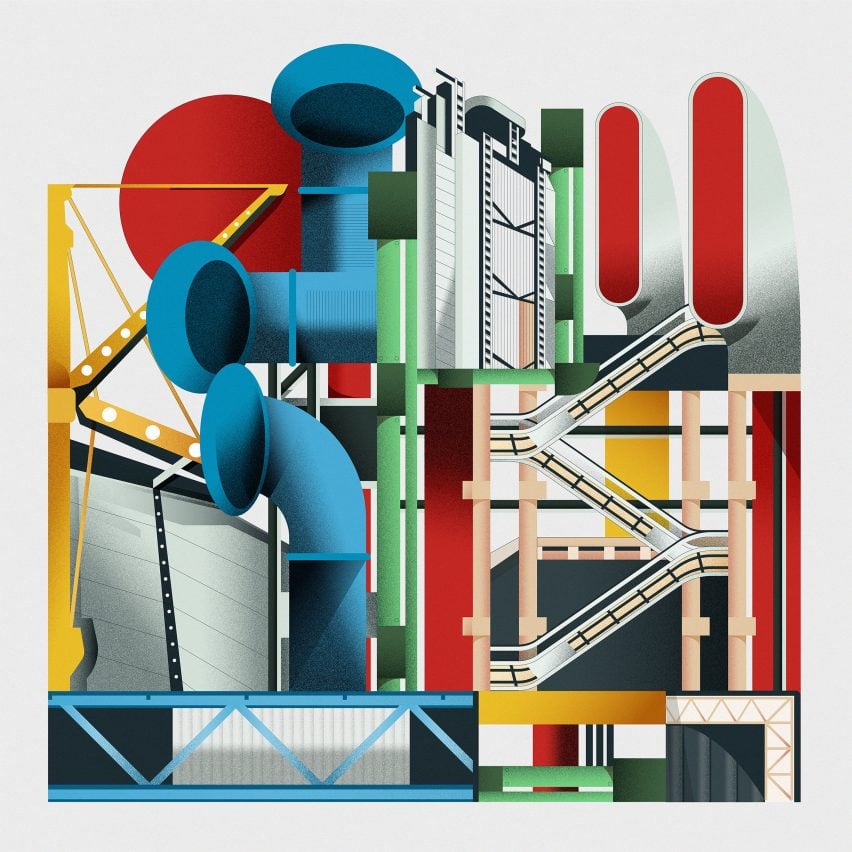

Inside-out is one of the most common ways of defining the buildings of Rogers – or to use a term coined by Archigram founder Michael Webb, "Bowellism".

This was an enduring stylistic motif of high-tech architecture – to express a building's services and allow pipes, elevators and structural members to be a visual element rather than hidden away in walls or concrete cores.

While often justified as a means of creating vast, flexible spaces, there was clearly a great aesthetic enjoyment being had here – not to mention expensive maintenance costs.

The two projects that define the career of Rogers remain the two most striking examples of this approach: the 1972 Centre Pompidou in Paris and the 1986 Lloyd's building. Both were incredibly lucky to actually be built given the opposition they received, standard fare for the early work of Rogers and fatal to some of the firm's other radical designs.

But if the historicism of Hopkins Architects or the sleek glass forms of Foster + Partners are considered dilutions of the original radical high-tech ethos, what defined the key works of Rogers' career was a refusal to compromise.

Rogers was born in 1933 into an Anglo-Italian family in Florence, where he lived for six years before moving back to England. Following a stint in the army, Rogers enrolled at the Architectural Association, where he met his future wife Su Brumwell who was studying at LSE.

Graduating in 1959 and soon to be married, the two went together to Yale, where Rogers would study for his master's in architecture on a Fulbright scholarship and Brumwell would study town planning.

Here the pair met Norman Foster, and after graduation Rogers joined him on an architectural road trip across America where many early influences were to be found, not only in projects like the Eames House but also the work of Louis Kahn, whose Richards Laboratories in Philadelphia with their "inside-out" layout would prove a key touchstone for Rogers.

While Foster returned to the UK, Rogers worked briefly in the offices of SOM, working with a style of structural expressionism that formed part of America's answer to Britain's high-tech. He quickly decided, however, as he states in his recent book A Place for all People, "working in someone else's architectural practice was not for me".

Returning to the UK the Rogers, along with Norman Foster and Wendy Cheeseman (soon to be married) formed Team 4 in 1963.

The practice's name was a conscious reference to the famous Team X which had included their former tutors the Smithsons, but it also demonstrated a disinterest in the cult of personality – surprising considering the level of architectural celebrity that the high-tech set would go on to achieve with Cheeseman, Brumwell and others like Patty Hopkins being frequently overlooked but key partners in their practices.

When Team 4 was dissolved in 1967 with Foster and Cheeseman setting up Foster Associates, Rogers and Brumwell established the short-lived Richard and Su Rogers Architects.

The studio would create a bright yellow home for Richard Rogers' parents (clearly inspired by the Case Study Houses they had seen in the USA) and an equally yellow concept called the Zip-Up House, a vision of a standardised modern home sponsored by DuPont that garnered the firm some publicity, but no commissions.

Just three years later the pair set on a new path, teaming up with Genoese architect Renzo Piano, who had recently moved to the UK to teach, to form the practice Rogers + Piano. While this partnership started small, with a project for Italian furniture manufacturer B&B Italia, it would soon make history.

In 1971, with the Rogers having just 14 projects under their belt (only seven of which had actually been built) Rogers + Piano, along with Gianfranco Franchini, entered the competition for the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Launched by the then French President, the project was envisioned as part of a series of schemes that would act as a social catalyst in a post-1968 Paris.

It was the first architectural competition of its kind in France to be open to architects the world over, attracting 681 entries from 49 countries – a rich mix among which Rogers + Piano were complete unknowns.

"It is our belief that buildings should be able to change, not only in plan, but in section and elevation, allowing people freedom to do their own things," wrote Rogers + Piano in their submission, which would be selected as the winner by a jury including modernist architects Oscar Niemeyer, Jean Prouvé and Philip Johnson.

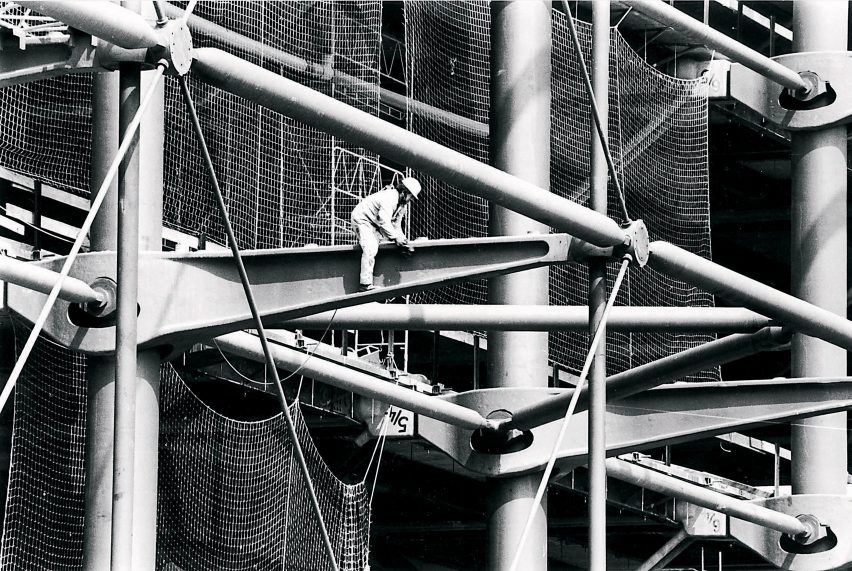

Flexibility was key to the practice's designs for Pompidou. The centre, which would only fill half the site in order to create a public piazza in front, was to be a framework able to change and adapt, with a structure designed by Ted Happold and Peter Rice of Over Arup and Partners covered in a colour-coded expression of the building's services.

As Rogers has stated since, the partnership had "no idea" what they were taking on: from the start these relatively unknown architects were at the centre of a controversy, and criticism from both the French and UK press. By the time the centre was opened by the new president Valery Giscard d'Estaing – Pompidou's rival – its status as a political monument remained only in name, but its status as an architectural one was secured.

Su Rogers, after early involvement in the Centre Pompidou's design, left the practice to become a Unit Master at the Architectural Association, and her and Rogers would divorce soon after, with Rogers marrying Ruth Elias in 1973.

Rogers and Piano, too, would soon part ways professionally, and in 1977 Rogers founded Richard Rogers and Partners, with an early success in 1978 when the partnership won a limited architectural competition to design a new headquarters for Lloyd's of London against proposals from both Foster and IM Pei.

Lloyd's was to be a further expression of the Centre Pompidou's inside-out nature. In its design, a central, barrel vaulted atrium containing a large underwriting floor (reminiscent of Paxton's Crystal Palace), is surrounded by six metal service towers containing the buildings services, lifts and prefabricated bathroom pods.

"The key to this juxtaposition of parts is the legibility of the role of each technological component which is functionally stressed to the full," said Rogers of the design.

Critic Owen Hatherley has referred to this approach, found in both Pompidou and Lloyds, as a "fearlessness and aggression".

While Foster Associates may have been far quicker to smooth out their radical high-tech ideas, and Hopkins Associates sought to make them civic and contextual with historicism, Rogers, at least until later in his career, was not prepared to make any such concessions.

Unsurprisingly, this saw the early years of Richard Rogers and Partners marked by a series of planning hurdles, one of which concerned a project at the centre of the mid 1980s "style wars" precipitated by Prince Charles – the National Gallery Extension.

Despite the architectural climate being one of so-called vernacular revival, the firm's submission to the 1982 competition was radically modern, proposing a Pompidou-like scheme complete with a high-tech spire and a new route to better connect Leicester Square and Trafalgar Square.

While Prince Charles' famous carbuncle speech was ostensibly against this competition's winning scheme by Ahrends Burton and Koralek, Rogers was evidently not in his good books.

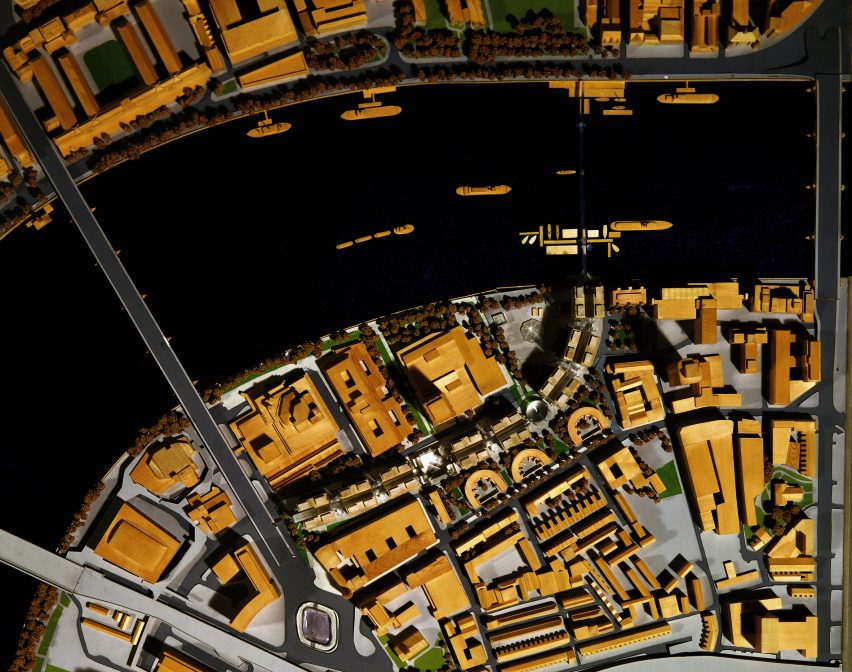

In 1987 Rogers proposal for Paternoster Square was scrapped, and another blow came when the Coin Street development of 1983 for London's Southbank was also abandoned after a planning battle.

In spite of the Pompidou being one of the most widely discussed pieces of architecture of the 1970s, it did not have the transformative effect on the practice that, for example, the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank had for Foster.

As Deyan Sudjic has written in his monograph on Rogers: "For a while it seemed that the Rogers office had become too controversial to get commissions from any clients not prepared to stand their ground and fight furiously for their right to choose the architect's ideas."

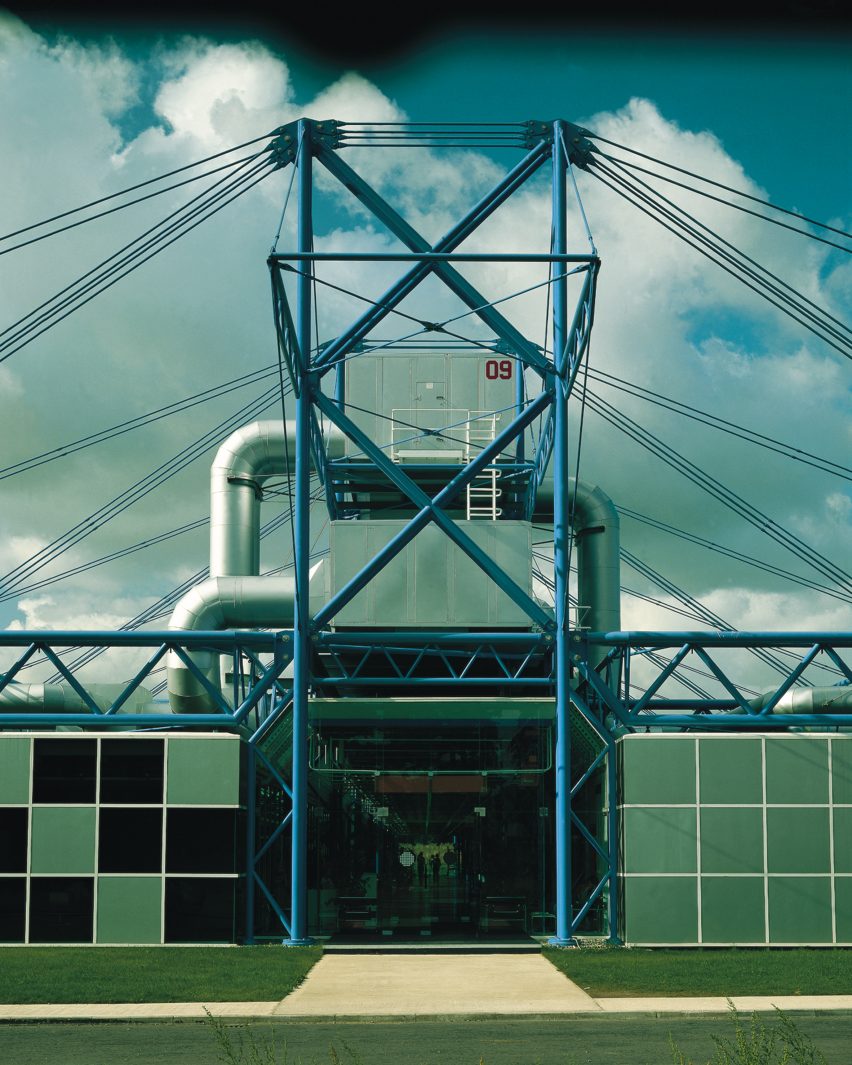

Occassionally these radical designs were allowed to play out, as in the 1982 commission from microprocessor firm INMOS, but this was to be the last example of a more radical high-tech one-off as the work of the practice continued its shift towards ideas of "urban renaissance".

These ranged from a masterplan for the banks of the Arno in Florence to proposals to demolish London's Hungerford Bridge and create a new river crossing peppered with floating cultural attractions. Then there were proposals for Potsdamer and Leipziger Platz in Berlin, and the Greenwich masterplan of 1997 that led to the Millennium Dome.

Following a knighthood in 1991 and being made a life peer in the House of Lords as Baron Rogers of Riverside in 1996, Rogers sat on several quangos, including the Urban Taskforce where he published Towards an Urban Renaissance published in 1999, which would be followed by Towards a Strong Urban Renaissance in 2005.

After 2000 the partnership completed numerous larger projects. There was an airport project for Heathrow's Terminal 5, the luxury flat blocks of One Hyde Park, NEO Bankside and Riverlight in Nine Elms, along with a skyscraper in the City of London, The Leadenhall Building, 3 World Trade Centre in New York and International Towers Sydney.

The radical high-tech of Rogers created compelling masterpieces but struggled to reconcile itself with larger-scale urban ideas. As so much of British high-tech demonstrated, the gulf between the imagined cities of the 1960s and 1970s and the realities that were actually shaping cities into the new millennium was vast.

Led by architects Foster, Rogers, Nicholas Grimshaw, Michael and Patty Hopkins and Renzo Piano, high-tech architecture was the last major style of the 20th century and one of its most influential.

Our high-tech series celebrates its architects and buildings ›

Main illustration is by Vesa Sammalisto, additional illustration is by Jack Bedford.