Inmos Microprocessor Factory is Richard Rogers' high-tech factory prototype

We continue our guide to high-tech architecture by looking at the Inmos Microprocessor Factory, a key example of Richard Rogers' radical inside-out buildings.

Completed in 1982 in Newport, Wales, the Inmos Microprocessor Factory is a highly-flexible single-storey steel structure that was conceived as a prefabricated kit of parts that could be constructed anywhere.

It contains a microchip factory, and like many of Rogers' other high-tech buildings, is identified by the outward expression of its structure and building services that help keep its interiors column free.

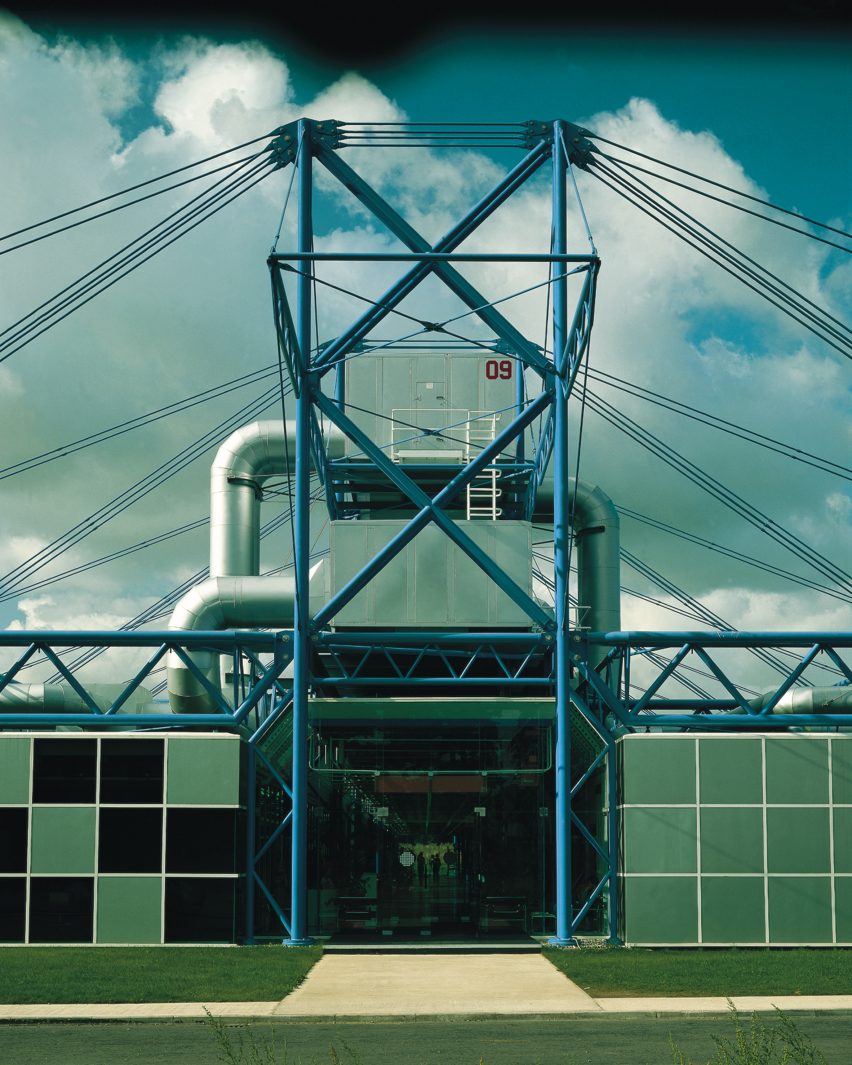

In the case of the factory, this emanates from nine blue-painted towers made from tubular steel that are positioned along the centre of its roof.

The Inmos Microprocessor Factory was the result of a government-backed commission from British semiconductor company Inmos to support the expansion of the Britain's emerging microchip industry.

It was developed by Richard Rogers Partnership, now Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, in collaboration with the high-tech engineer Anthony Hunt as a model microchip factory that could be quickly and easily replicated in any location.

The technical requirements of the brief from Inmos called for an area dedicated to the microchip production with controlled clinical conditions protected from dust and vibration, while offering more open offices and a staff canteen under the same roof.

However, it simultaneously demanded that the building should be completed within one year of construction beginning on site with the potential for extension that wouldn't impact production.

Rogers and Hunt's solution was to develop a kit of parts that could be prefabricated off site. Made as large as possible, these prefabricated elements were then transported to site and efficiently craned into position.

The final structure consists of 16 equal-sized bays, each measuring 13 by 36 metres, which were built one by one to form a rectilinear building.

These bays are positioned either side of a central spine, which runs the length of the building like an internal street, and divides it into two wings.

The corridor measures 7.2 metres in width and is 106 metres long, designed by Rogers to be wide enough for vending machines, telephones, seating and planted areas.

On the north side of the spine, the building contains a "clean" area for microchip production. Meanwhile the south side has a "dirty" ancillary area, which includes the offices and a restaurant. One bay in the middle is used as a landscaped courtyard for workers.

The architectural critic and writer Reyner Banham referred to the Inmos Microprocessor Factory as "the first really challenging building of the 1980s".

To ensure all these bays are left uninterrupted and column-free for flexibility, the Inmos Microprocessor Factory's structure and building services are all positioned above the building on its roof.

The building's exoskeleton is built of nine blue steel towers that are positioned in line with the central corridor and are attached to 40-meter-long trusses that extend either side from it. These trusses are supported by tension rods.

The towers enclose a series of double-storey service pods and plant rooms, from which all ductwork feeds out across the building's flat roof and into the ceilings of the bays.

All of the Inmos Microprocessor Factory's external walls were designed to be customisable – based on a system of standardised mullions that can be fitted with infills ranging from single or double glazing to translucent or opaque panels.

"The plant's demands did indeed dictate the design. But the architecture eventually seized control," said American author and journalist Lincoln Caplan in The New Yorker in 1988.

Led by architects Norman Foster, Rogers, Nicholas Grimshaw, Michael and Patty Hopkins and Piano, high-tech architecture was the last major style of the 20th century and one of its most influential.

High-tech is an architectural style that emerged in the UK in the late 1960s, which saw the expression of structural elements and building services usually hidden within buildings.

Our high-tech series celebrates its architects and buildings ›

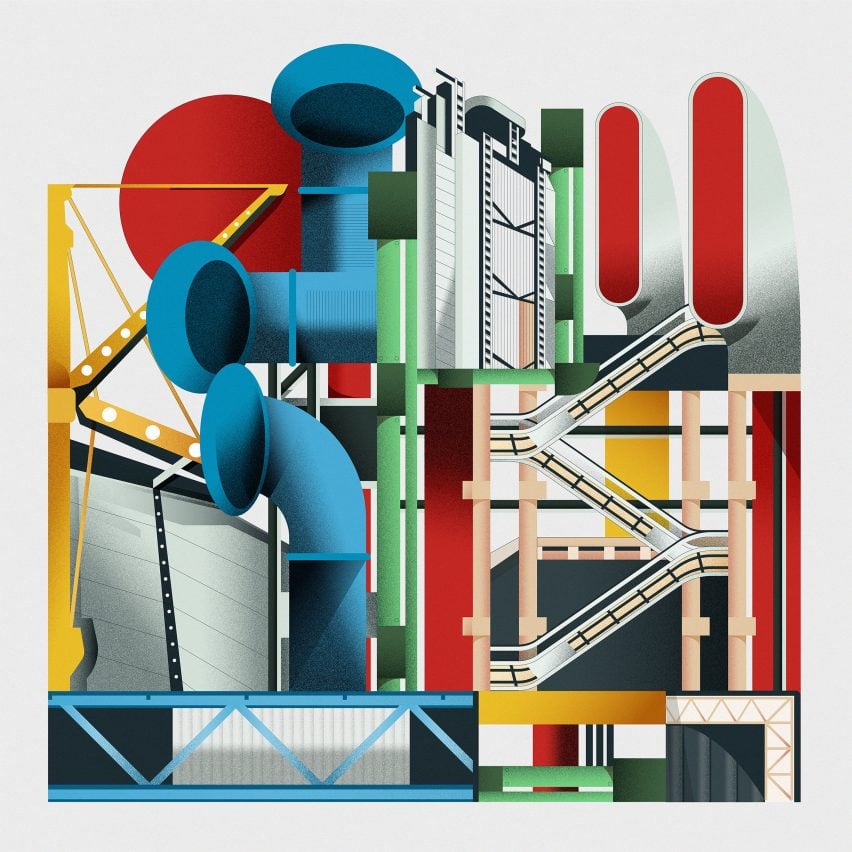

Illustration is by Jack Bedford. Photography is by Ken Kirkwood, courtesy of RSHP.