Herman Miller Factory was a flexible, non-monumental high-tech factory

We continue our high-tech architecture series by looking at the highly flexible and adaptable Herman Miller Factory in Bath, which was designed by Terry Farrell and Nicholas Grimshaw in 1976.

The factory for the furniture company was one of many high-tech buildings, including the Park Road Apartments completed by Farrell Grimshaw Partnership six years earlier, which was designed to have flexible interiors.

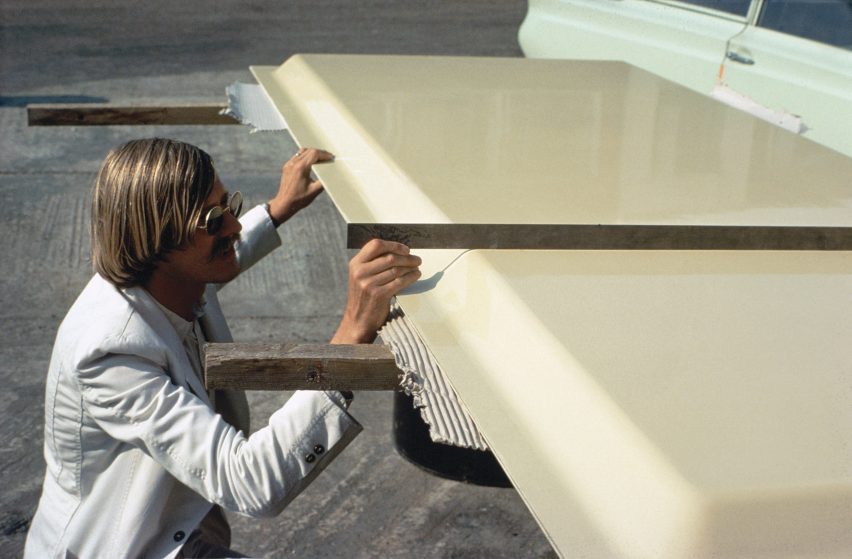

The flexibility of the interiors was matched with the pale-yellow panelled exterior cladding, which is demountable, interchangeable and reconfigurable.

The open-plan layout within the factory was designed to reflect the office furniture Herman Miller was producing and to be flexible to suit future manufacturing demands.

Grimshaw was influenced by the modular design of the company's furniture and wanted to name the building Action Factory – after the brand's Action Office furniture – as the flexibility of its mobile elements were vital to the architectural design.

"We wanted a level of flexibility that wasn't available in contemporary buildings at the time," said Bob Wood, vice president for research, design and development at Herman Miller. "I think that's what made it revolutionary."

The Farrell Grimshaw Partnership was selected to design the manufacturing facility from a shortlist of architects, which included fellow high-tech architect Norman Foster and James Stirling. Max de Pree, son of Herman Miller founder DJ de Pree, wanted a factory that would "change with grace, be flexible and non monumental".

"Herman Miller's brief looked for a building that they could change and alter. The building would look after them," added Grimshaw in a video about the project.

"In that sense, the building and the furniture was to support human activity, and not the other way round. And that appealed to us a lot."

Located by the River Avon, the factory has a rectangular plan. Its structure uses primary beams intersecting at columns, with thinner, secondary beams laid perpendicular in between the primary ones at frequent intervals.

This structure, called a primary and secondary beam system, is laid on a 10-by-20-metre grid with only two rows of nine columns running through the open interior.

Like its high-tech predecessor the Reliance Controls Factory, the structure and services were visible from the factory floor.

The factory's services ran along the perimeter, fitted around courtyard indentations where employees could sit outside in sheltered hubs. These break areas were eventually removed so newer, larger machines could run along the sides of the building.

Standing almost six metres high, the building's ceiling space allowed for tall manufacturing equipment and could be used to store pallets. The tall room height also contained factory utilities, accessed via hanging walkways.

The flexible structure is covered with an equally flexible exterior. It is clad with a plastic, modular skin that was designed to accommodate future changes.

Grimshaw and Farrell developed the modular system of insulated panels to be completely demountable. The system has interchangeable pieces of fibreglass, louvre shutters and glazing that could easily be rearranged as it was separate from the building's structure.

Herman Miller employees could switch the panels based on the internal arrangement, without having to employ skilled labourers. An easy-to-use, neoprene top-hat-like cap fixed between two panels when mounted.

At the time, windows were an uncommon feature in conventional factory design. By implementing optional windows into the cladding system, Herman Miller Factory staff could enjoy daylight and views to the riverbank from the factory floor.

Herman Miller occupied the factory for 15 years, during which the exterior and interior was rearranged a total of five times.

Earlier this year, the highly flexible building was reconfigured once more to become Bath Spa University's Locksbrook Campus.

The building was granted a Grade II listing in 2013, recognised for its impact on industrial workplace design and its high-tech architecture features.

Known to have formed a relationship with Herman Miller, which is still prevalent today, Grimshaw has designed several consequent factories. His third for the company located in Melksham opened in 2015, almost 40 years after the first in Bath.

Emerging in Britain during the late 1960s, high-tech architecture was the last major style of the 20th century and one of its most influential. Characterised by buildings that combined the potential of structure and industrial technology, the movement was pioneered by architects Norman Foster, Richard Rogers, Grimshaw, Michael and Patty Hopkins and Renzo Piano.

Our high-tech series celebrates its architects and buildings ›

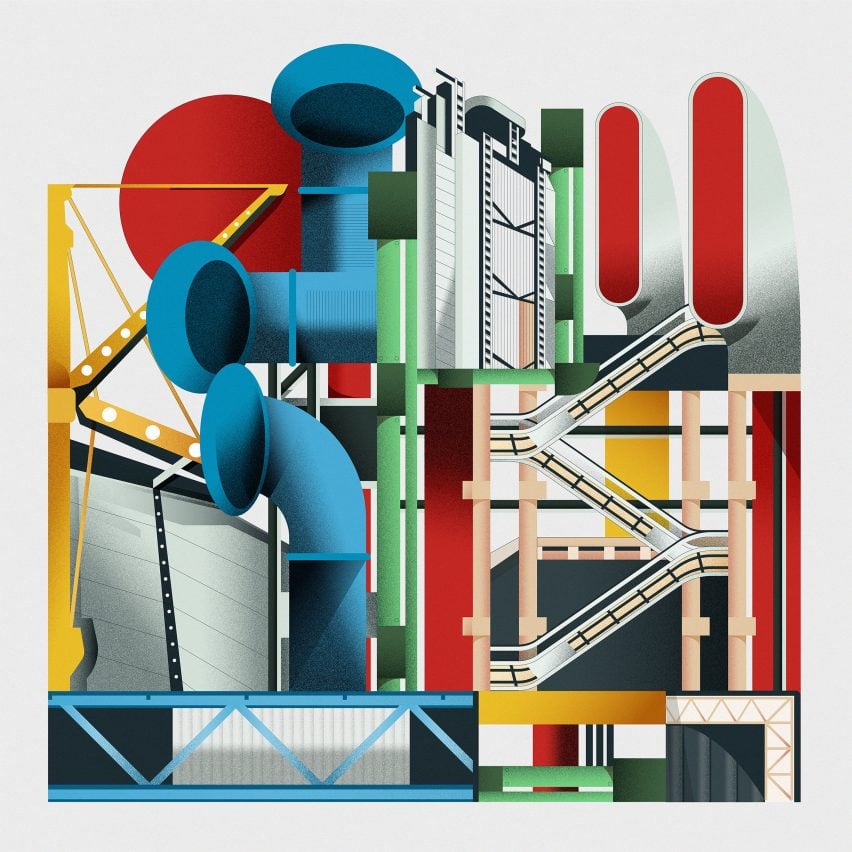

Photography is by Jo Reid and John Peck. Illustration is by Jack Bedford.