Detailed photos of 80 Chinese buildings feature in Kris Provoost's book Beautified China, which spotlights the country's current architectural boom.

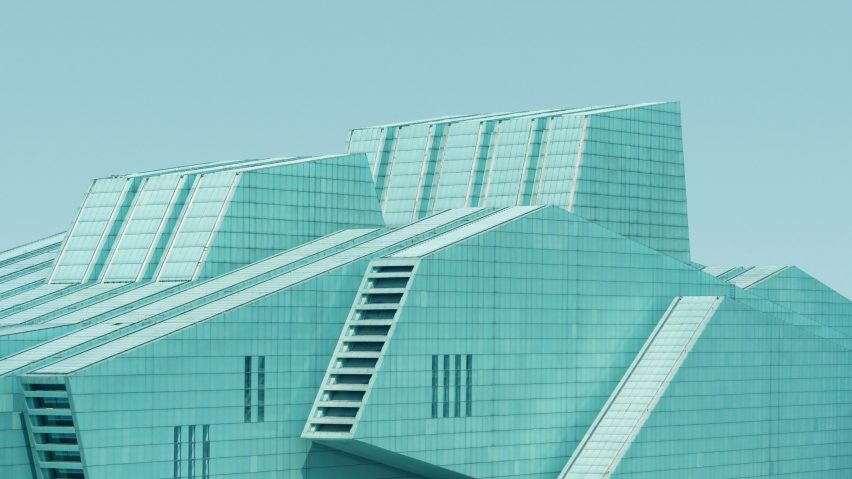

The book is an expansion of the Beautified China photography series that Provoost revealed in 2017, in which "iconic architecture" by the likes of Zaha Hadid, MAD and Foster + Partners is depicted as abstract forms against bright blue skies.

It has been curated by Provoost for publisher Lannoo to offer an overview of China's rapid emergence as a hotspot for contemporary architecture in the past 15 years.

From OMA's CCTV Headquarters through to lesser-known buildings like Bernard Tschumi Architects' Exploratorium museum, the book features photos of structures in 16 different cities in China.

Other projects featured in the book include Zaha Hadid Architects' Meixihu International Culture and Arts Centre, the sinuous Harbin Opera House by MAD and The Fosun Foundation by Foster + Partners and Heatherwick Studio.

"During the many travels through the country to document the architecture, it became clear there was a real architectural revolution going on, with an endless supply of projects of all sizes and shapes," Provoost told Dezeen.

"There are about 80 different buildings from 16 Chinese cities in the book. For me it was important to provide a mix of projects for the far extent of the country," he explained.

"The aim was to give a broad overview and show the massive scale at which architecture is used in China to develop the country."

Alongside Provoost's photography, Beautified China is complete with a series of essays on architecture in China by five different authors with different backgrounds and focus.

This includes a foreword by Nikolaus Goetze, partner at GMP Architekten, which explores what the future could look like for architecture in China.

Provoost, who is also a practicing architect, became interested in the country's booming construction scene in the run up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

According to Provoost, this event marked the beginning of China's architectural revolution, as the country invited "starchitects to build their wildest fantasies".

"When China was awarded the 2008 Olympics, they started proposing extraordinary architecture," he said.

"That was the time I became fascinated with China. When I graduated from architecture school in 2010 I went to China to see it for myself and haven't left ever since."

Provoost's decision to photograph key details of buildings – opposed to complete structures in context – is influenced by his practice as an architect.

"My background in architecture influences everything I do as an architecture photographer. I always search for the best proportions and that special feature that makes it stand out," said Provoost.

"For that I tend to zoom in to purify that element. Be it, a unique shape, a special facade feature, the colour, a special pattern."

Having now spent 10 years documenting architecture in China, he has also observed a number of shifts in style in the country's construction industry.

Though the book documents unusual, statement architecture, Provoost said the most predominant trend is a move away from the creation of this "iconic architecture". Instead, many architects are now focusing on the preservation of existing structures.

"The trends that struck me over the past decade is that the iconic architecture trend – that is portrayed in the book – is slowly fading away," he said.

"Instead there is a focus on preservations. Old factories are being reprogrammed to house musea or cultural centres. While the trend of iconic architecture, in my opinion, will never fully fade away, it became of less importance."

Provoost believes that this is partly due to the comments made by Chinese president Xi Jinping in 2014, who called for an end to the "weird architecture" in the country.

"The comments from Xi definitely had an impact and architects had to adjust. The architecture that gets build now definitely doesn't scream that loud anymore, it is more refined now with more care for the existing context," explained Provoost.

"Most cities are developed to a certain degree and the purpose of this kind of architecture is becoming secondary. It is a very welcoming shift that gives space for a different kind of architecture to develop in China."

Though the drive for "iconic architecture" may be fading away, Chinese cities are continuing to rapidly develop.

In 2019, the country built more skyscrapers over 200 metres than any other in the world – accounting for 45 per cent of the global total. This included Kohn Pedersen Fox's 400-metre-high supertall skyscraper in Shenzhen, and Zaha Hadid Architects' Leeza Soho with the world's tallest atrium.