SheltAir gridshell pods inflate in eight hours to isolate coronavirus patients

Architectural engineer Gregory Quinn has developed SheltAir, domed bio-containment pods erected using inflatable cushions that could help coronavirus patients isolate.

SheltAir consists of a gridshell of plastic rods, which is assembled flat before being pushed up into its final, domed shape through a pneumatic formwork of inflatables.

This blow-up cushion is made of PVC-coated polyester. It stays in place once inflated, doubling as the building's architectural envelope.

The envelope is heat-welded to an outer skin to create a completely sealed environment, which is crucial when it comes to isolating with a virus like Covid-19.

"One of the problems that hospitals are facing is that staff and visitors are at risk of infections," Quinn told Dezeen.

"So smaller units of containment make a lot of sense. To create negative pressure and filter out any particles or droplet you need a sealed environment," he added.

"Some people have been proposing converting shipping containers into ICUs but sealing them is a real challenge, whereas the SheltAir comes pre-sealed."

The design has been passed on to the World Bank to assess a potential roll-out in the fight against the coronavirus. Quinn is currently in talks with medical evacuation, or medivac, companies about getting the design into the field.

A key benefit SheltAir's gridshell structure, which was popularised by German architect Frei Otto, is that its lattice skeleton is lightweight. It uses minimal material while remaining incredibly sturdy through its double-curved structure.

"It's sort of like an egg shell which is very stiff given how light and thin it is," Quinn explained.

"So in their end state, gridshells are incredibly efficient but the erection process has historically been abysmal. It can take days and weeks because you either have to lift it up with a crane or push it up with stilts or scaffolding, which is unstable and a logistical nightmare."

Quinn's solution of introducing pneumatic cushions, which are often used to erect concrete shells, minimises erection time to eight hours – and in future prototypes he is hoping to cut this time by half.

The method for setting up the SheltAir is purposefully low-tech and low-skill.

It starts with a ground sheet that comes complete with drawn-on instructions and is laid out to serves as a template for the building.

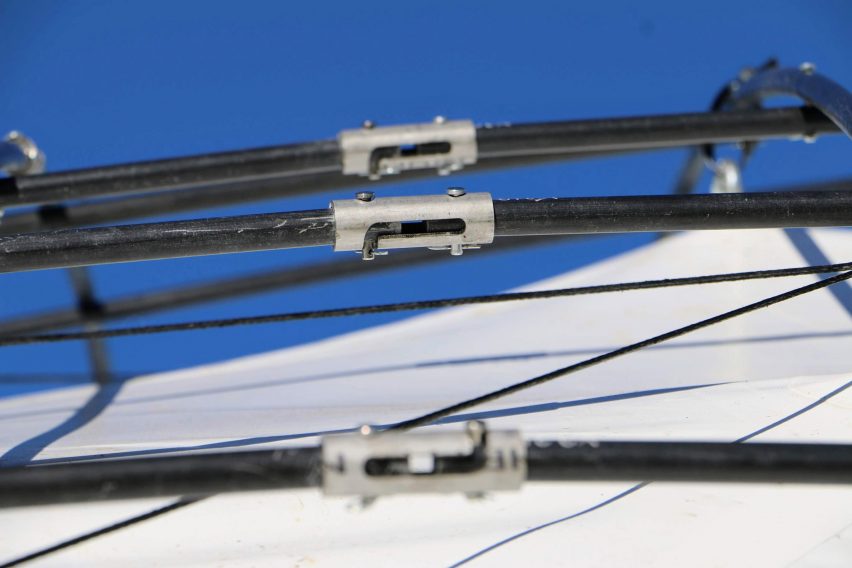

"The glass fibre-reinforced rods of the gridshell come collapsed in pre-assembled bundles, which are flipped open to form six large rod tiles and connected together on top of the ground sheet," he said.

"Laser-cut steel plates are assembled along the perimeter of that sheet. Once the structure is inflated, the beam ends stick out of the edge of the cushion and need to be pulled down to their support points in the perimeter plates, sort of like with a tent."

The SheltAir was originally conceptualised as a rapid disaster relief shelter for refugees, as part of the Healthy Housing for the Displaced (HHftD) project from the University of Bath and Cambridge.

For this purpose, the grid structure offers more than 100 hanging points for lights, utensils and partitions to accommodate more than one family in the same space, while the addition of portholes allows for easy ventilation in hot climates.

"The design is heavily influenced by Bedouin architecture, and it exploits those openings at the perimeter and the opening at the top to create a really effective nighttime purge cooling," he explained.

"The idea of using soft petition curtains also played into this idea of keeping one volume of air that is always moving."

Quinn is working with charities with the aim of introducing SheltAirs into refugee camps in the coming months.

"It's really hard to innovate in terms shelter design and disaster relief response because when the crisis hits people just need to respond really quickly and go with the solution that's most readily available," he explained.

"That's why the need for larger, communal spaces – for medical treatment and social or religious gathering – is never really catered to. But the coronavirus pandemic is a unique crisis because it's happening everywhere. Each country is being affected at a different rate and at a different time, so it actually presents a really interesting opportunity for a more considered approach."

The coronavirus has now infected more than half a million people around the world, with numbers continuing to climb.

In response, Italian firm Carlo Ratti Associati has unveiled plans for creating intensive care pods within shipping containers, while start-up Jupe has designed flat-packed, pop-up health care facilities.

Meanwhile the American Institute of Architects is working on a set of guidelines on how to safely and effectively convert existing buildings into temporary hospitals.