From designing face shields and flat-pack intensive care units to 3D-printing hands-free door levers and converting buildings to hospitals, architects and designers are tackling the coronavirus pandemic. Here are five ways they are helping.

Converting buildings to hospitals

The unprecedented number of coronavirus cases is forcing countries around the world to rapidly increase their capacity to treat patients.

To do this, buildings across the world are being converted into intensive care units. In Tehran, Iran Mall, the world's largest shopping centre, is being transformed into a coronavirus hospital, while in New York the Cathedral of St. John the Divine is also set to be converted.

With large open spaces, conference centres are an obvious choice for conversion and architecture studio BDP has converted the ExCel Centre in London into a 4,000-bed hospital called NHS Nightingale.

Two giant wards have been created in the exhibition halls, which are divide from a central corridor by areas to put on and take off protective clothing. A staff canteen, diagnosis room and mortuary complete the hospital.

"When the scale of the shortfall in beds across London became clear, the ExCel centre was the obvious choice," BDP's James Hepburn told Dezeen.

"It has huge flat floor hall spaces with flexible MEP infrastructure that can be easily adapted to meet the needs of the temporary hospital."

Designing temporary intensive care units

Architects have also recognised the need to create temporary intensive care units that can be rapidly deployed, following China's rapid construction of a temporary hospital to treat patients at the start of the pandemic.

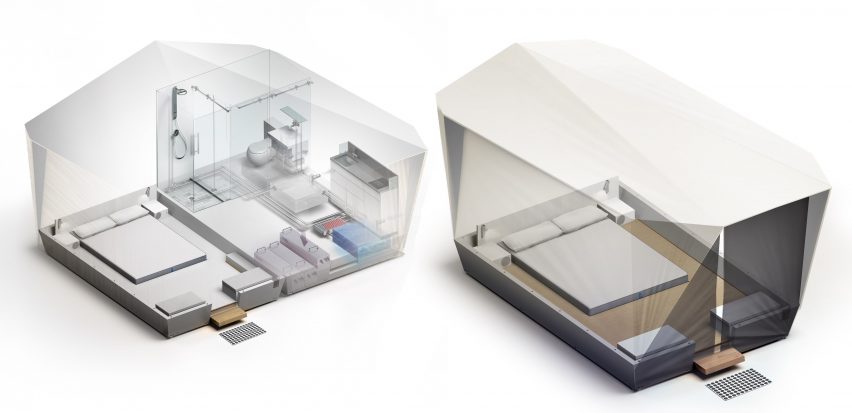

In response to the outbreak in the USA, flat-pack startup Jupe has created a range of medical care facilities that are designed to be quickly installed at hospitals to increase bed capacity, or that could be used as stand-alone field hospitals.

"Hospitals can't tackle it all rapidly enough, even once the federal government's aid package kicks in," explained Jupe chief medical advisor Esther Choo.

In Italy, architects Carlo Ratti and Italo Rota designed an intensive-care pod within a shipping container. The first prototype is currently under construction at a hospital in Milan.

In some countries, the pandemic has led to a shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) to protect health workers. In response, architects and designers have begun designing and manufacturing it themselves.

In the USA, studios including BIG, KPF and Handel Architects have joined an open-source project to print face shields, while in Spain 3D-printing brand Nagami Design has switched its machines from making furniture to shields.

British architecture studio Foster + Partners decided to design an alternative face shield that can be laser cut. The open-source device can be disassembled and sanitised for reuse.

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the University of Cambridge and the University of Queensland, and graduates from Rhode Island School of Design have all also designed face shields.

MIT has developed a disposable face shield that is made from a single piece of plastic, which can be mass-produced and shipped flat. Pieces of plastic and be folded into a three-dimensional structure when needed.

The RISD graduates created a simple shield that combines a curved piece of plastic with a headstrap, while the University of Cambridge and the University of Queensland's design can be created with no specialist materials or tools.

Making face masks

Face masks are another item of PPE that have seen a massive increase in demand during the pandemic. In response to shortages, numerous designs and fashion brands have converted their factories to mask production.

Prada, COS and Louis Vuitton are among the leading brands that have retooled to manufacture surgical face masks, while Yves Saint Laurent and Balenciaga have begun production of cotton face masks.

Hacking equipment

Architects and designers have been using their 3D-printers to quickly create items that alter equipment to solve problems raised by the pandemic.

To make wearing face masks less painful for medical staff treating patients, Chinese 3D-printer manufacturer Creality is printing a device that holds the strings away from the wearer's ears.

Architectural designers Ivo Tedbury and Freddie Hong have created a 3D-printed door-handle extension that users can loop their arm through so they can open doors without using their hands.

In Italy, additive manufacturing start-up Isinnova reverse engineered and 3D-printed a crucial valve for a oxygen mask, which is used as part of a ventilator machine, following a shortage.

"The valve has very thin holes and tubes, smaller than 0.8 millimetres – it's not easy to print the pieces," said Isinnova CEO Cristian Fracass. "Plus you have to respect not [contaminating] the product – really it should be produced in a clinical way."