Sara Sallam's Orwell jewellery thwarts invasive tracking technology

Brooklyn-based designer Sara Sallam has imagined a collection of jewellery and accessories to protect the wearer from tech-enabled surveillance without concealing their features.

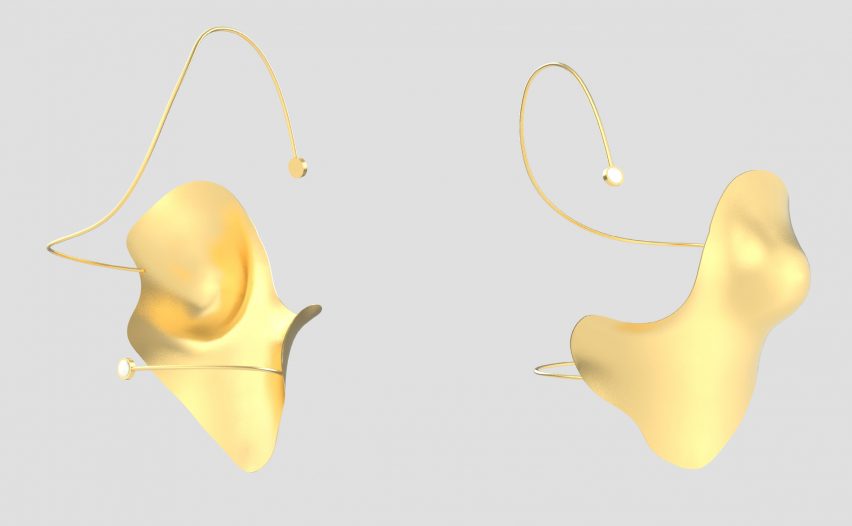

Taking its name from George Orwell, author of dystopian novel 1984, Sallam's project comprises three pieces of jewellery worn on the face, chest and foot.

Each of the wearables work to protect the user's identity from facial recognition, heartbeat detection or gait-tracking technology while still being visually appealing.

"There are several solutions to these tracking technologies created by designers and engineers with various success, but most obscure or change the user's appearance to the point of grotesqueness," the Appalachian State University graduate told Dezeen.

"I wanted to create objects for an Orwellian future where this surveillance is commonplace, and as such, the form needs to appeal to people's sense of aesthetics and still allow the wearer to be identifiable to the people around them."

Each piece would have a ripple-like effect reminiscent of pearl. Sallam chose this finish as a reference to Lover's Eye jewellery, miniature paintings popular in the 1700's that featured an eye, often surrounded by pearls.

The jewellery aims to offer a solution to and refuge from the growing presence of surveillance in countries across the globe, which can be used as a method of state control.

"The creeping rise of this tech is often overlooked, but this kind of unwarranted surveillance poses a threat to our personal liberties," Sallam told Dezeen.

"Facial recognition is becoming another tool of our hyper-militarised police, and misidentifies people of colour up to 100 times the amount that it misidentifies white people."

"Most recently, it is being used to identify and arrest protestors, with the FBI notably asking for photos and videos of the Black Lives Matter protests currently sweeping the country," she continued.

"With the rapid expansion of this technology, the question is not whether this technology will play a huge role in our societies future – but what will it look like when it has?"

Sallam developed her project as a follow up to Ewa Nowak's anti-AI Incognito mask. The designer appreciated the mask's beautiful design but noticed that tracking technology had advanced so rapidly that the mask was no longer effective against certain types of recognition.

This includes Amazon Rekognition – the facial recognition software most commonly used by the American police force.

While Nowak's mask was intended only to fool Facebook's AI technology, Sallam still wanted to create an more updated form of the anti-tracking jewellery.

Unable to make physical prototypes of her designs when her university closed due to coronavirus, Sallam digitally created each using a 3D scanner and various 3D modelling and rendering programs.

The facial jewellery works in three ways. Firstly, by obscuring key facial geometry – the area where the nose and eyebrows meet and the chin – and secondly by decreasing the facial symmetry.

It also alters the wearer's facial landscape via its highly reflective material, which distorts patterns of light and dark across the face.

When tested against Amazon Rekognition, Sallam's face piece lowered the software's "confidence rate" in identifying someone from zero to 92 per cent.

"The goal was to lower the confidence rate to 90 per cent, as anything under 99 per cent can't be used in court as the US laws stand)," she explained.

The armour-like chest piece protects against heartbeat detection technology – a very recent technology, according to the designer, owned by the Department of Defence, which uses lasers to detect heart rhythm on the skins surface.

"Not a lot is known about this technology yet, but it can currently be deterred by wearing thick clothing," said Sallam. "But anticipating rapid new advances, I created a lightweight piece that covers the most susceptible areas of skin where lasers could pick up the heart's rhythm."

Described by Sallam as a piece of armour, the chest jewellery was designed with the shape of a traditional breastplate while still looking "non-combative" enough for daily wear.

The final shoe accessory works by interrupting gait recognition technology, which Sallam says has an 80 per cent accuracy rate in identifying an individual.

She took inspiration from "the oldest trick in the book" of placing a pebble in your shoe. Designed to be worn on one foot, the design works by lifting the ball of your foot up just enough to interrupt bipedal symmetry.

It is designed with a modularity that allows it to be switched from one foot to the other to avoid straining one side of your body.

Sallam is not the only designer to create objects as a response to the growing use of surveillance.

Katja Trinkwalder and Pia-Marie Stute developed a series of add-on accessories that use fake data to stop your devices spying on you, while US start-up Winston Privacy created a hardware filter to give people control over their online privacy.

Photography is by Jesse Maltby.