Swiss designer Yves Behar has unveiled his design for French ocean conservationist Fabien Cousteau's underwater pressurised research station that will be "the ocean's equivalent to the International Space Station".

Behar designed the station, which is called Proteus, for the Fabien Cousteau Ocean Learning Center. It will have its own greenhouse to allow scientists to grow their own food 18 metres under the sea near Curaçao, an island in the Caribbean.

Up to 12 researchers and aquanauts – scientists who remain underwater breathing pressurised air for over 24 hours – will be able to live in Proteus at a time.

Like the International Space Station, Proteus will allow scientists to collaborate and make new discoveries in an inhospitable environment.

"The research station will enable the discovery of new species of marine life, create a better understanding of how climate change affects the ocean, and allow for the testing of advanced technologies for green power, aquaculture, and robotic exploration," Behar told Dezeen.

Living underwater in a pressurised environment, rather than just diving in, allows scientists to spend far more time in the water and only decompress at the end of their assignment.

Proteus is the result of Behar's studio Fuseproject being commissioned by Cousteau, and his non-profit the Fabien Cousteau Ocean Learning Center (FCOLC).

"We needed to understand the constraints that come from building underwater and the challenges of living in an underwater structure," Behar said.

"The social isolation, the humidity, the lack of light and lack of exercise all needed to be addressed," he explained. "I learned about these challenges from Fabien, who had the record as the person who lived longest in an underwater habitat."

Cousteau broke the record, previously set by his grandfather, with a 31-day-long stay in an underwater laboratory off the coast of Florida called Aquarius.

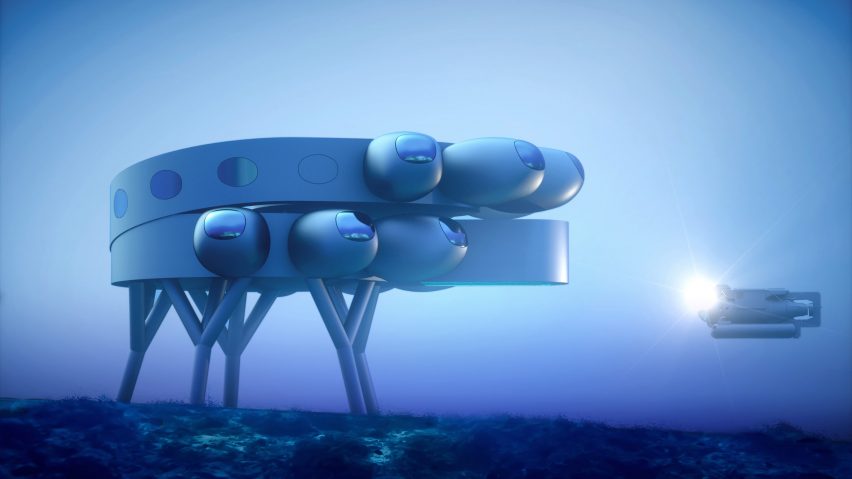

Behar used Cousteau's experience to inform the design of Proteus, which has two levels connected by a curving ramp with pods set around the edges.

Circular-shaped main spaces are designed to encourage teamwork and social interaction for the scientists. Pods around the perimeter are designed to hold specific laboratories, bathrooms and areas for sleeping.

"Both circular floors are offset to allow as much natural light as possible through skylights and portholes, and are connected by a sloping ramp which creates the opportunity for physical activity," said Behar.

Social spaces will be kept separate from the more humid areas of the wet labs and the moon pool – the space in an underwater habitat where occupants can access the water directly in a protected environment.

An underwater greenhouse will allow occupants to grow their own food, allowing them to stay underwater for longer and cope more comfortably with the confines of a pressurised environment where no open flames for cooking are allowed.

Behar deliberately gave the underwater habitat a retrofuturist vibe in keeping with the way science fiction has traditionally imagined underwater living.

"Fabien and I looked at many exploratory designs from the 60s and 70s, a golden era of interest for the oceans pioneered by the Cousteau family history," Behar told Dezeen.

"We felt that Proteus could incorporate a new visual language based on modern hull and composite building technology, as well as be a state-of-the-art scientific environment while delivering a comfortable social interior space."

In keeping with the Cousteau dynasty's ocean conservation goals, Proteus will be powered by renewable energy. The habitat will use a mixture of wind, solar and Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC), a process that produces electricity using the difference in temperature between warm water on the surface and cold water from the deep ocean.

Cousteau will head to Curaçao to map the site as soon the borders shut due to the coronavirus pandemic open, hopefully in September. Behar estimates it will then take 36 months to build and lower Proteus to the ocean floor.

Behar hopes Proteus will be one of a series of marine habitats dedicated to research and conservation. As well as scientists, the designer hopes the facility will be able to welcome civilian visitors.

"Proteus is designed to be a scientific environment, but also to create that desire in people to want to visit," he said.

"For me, it’s a lot more exciting to visit Proteus than going to Mars."

Behar embraces technology with his designs, which include plans for 3D-printed houses for impoverished farmers and a wearable UV sensor to protect against skin cancer.