TômTex is a leather alternative made from waste seafood shells and coffee grounds

Vietnamese designer Uyen Tran has developed a flexible bio-material called TômTex, a leather alternative made from food waste that can be embossed with a variety of patterns to replicate animal leathers.

The name tôm, meaning shrimp, references the discarded seafood shells that are mixed with coffee grounds to create the textile.

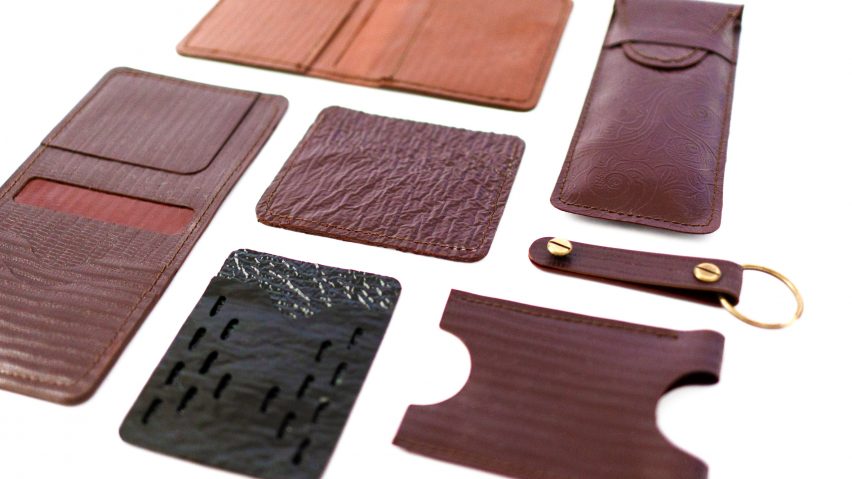

According to Tran, the biodegradable material is durable while remaining soft enough to be hand-stitched or machine-sewn.

"I grew up in the city of Da Nang, where leather textiles were predominantly manufactured," she told Dezeen.

"Leather is used in so many applications across different industries but people around the world are suffering from the pollution that the industry causes."

In a bid to kill two birds with one stone, Tran developed a substitute using an abundant, natural resource – food waste.

Every year, up to eight million tonnes of waste seafood shells and 18 million tonnes of waste coffee grounds are generated by the global food and drinks industry.

"The world is running out of raw materials, so I want to repurpose these wastes into a new, accessible bio-material for everyday life to help people better understand the problem and contribute to making a change," Tran explained.

The New York-based designer works with a supplier in Vietnam, who gathers waste shrimp, crab and lobster shells as well as fish scales, to extract a biopolymer called chitin from them.

This is found in the exoskeleton of insects and crustaceans, rendering them both tough and pliable at the same time. Combined with waste coffee from Tran's own kitchen and from local cafes, this forms the basis of Tômtex.

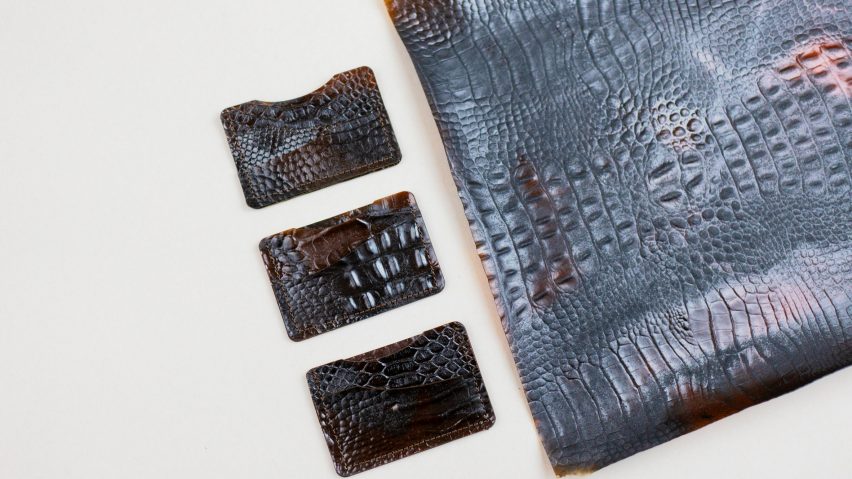

The mixture is dyed using natural pigments such as charcoal, coffee and ochre to create a variety of colour options.

"After mixing all the ingredients, the bio-material can be poured into the mould where it is air-dried at room temperature for two days," said Tran. "The process doesn't require heat, therefore it saves more energy and reduces carbon footprint."

Crucially, rather than leaving the material to cure in a perfectly smooth mould, the designer crafts her own from clay or using a 3D printing process.

This allows her to create her own finishes, which are able to mimic the look of snakeskin or crocodile leather as well as more abstract embellishments.

"Tômtex can replicate any textural surface, so there are endless possibilities for pattern design," said the designer.

"It also can be customised to be either leather-like, rubber-like or plastic-like by adjusting the formula and the way of production. So the possible applications go beyond fashion to packaging, interior or industrial design."

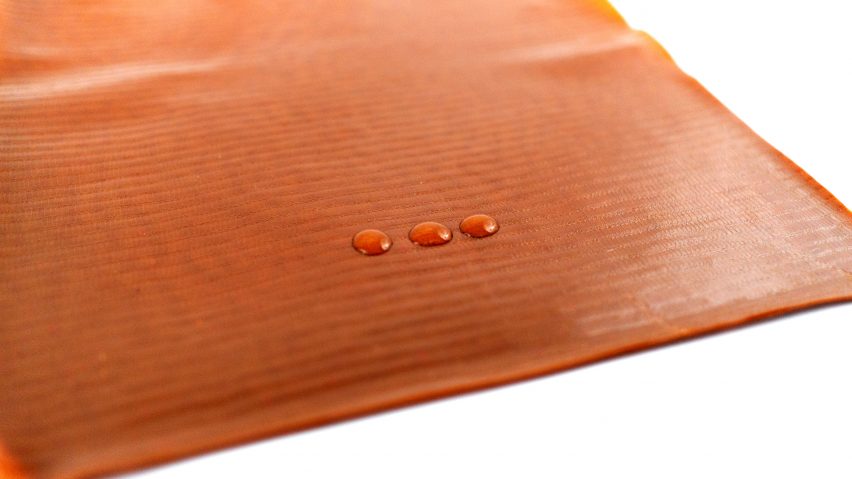

The resulting material is also naturally water-resistant, a feature that can be enhanced by adding a coating of beeswax on top.

When a Tômtex product has reached the end of its life, Tran claims it can be either recycled or be left to biodegrade.

"The recycled Tômtex bio-material has the same high performance and quality of the original, so it maximises the product's life cycle while minimising the negative impact on the environment," she explained.

"Beyond that, I don't believe in designing something that lasts forever. If Tômtex ends up in the landfill, it will fully biodegrade in the natural environment in a few months and can act as a fertiliser for plants."

Previously, chitin derived from the exoskeleton of crustaceans or insects has mainly been used to create a variety of harder, more structural bioplastics.

A group of students from London's Imperial College and the Royal College of Art turned seafood waste into a single-use plastic alternative, for use in everything from blister packaging for medication to food-safe carrier bags.

Meanwhile, Dutch designer Aagje Hoekstra used the armour of dead Darkling Beatles to create her Coleoptera bioplastic.