Chila Kumari Singh Burman overwrites Tate Britain's neoclassical facade with neon Diwali installation

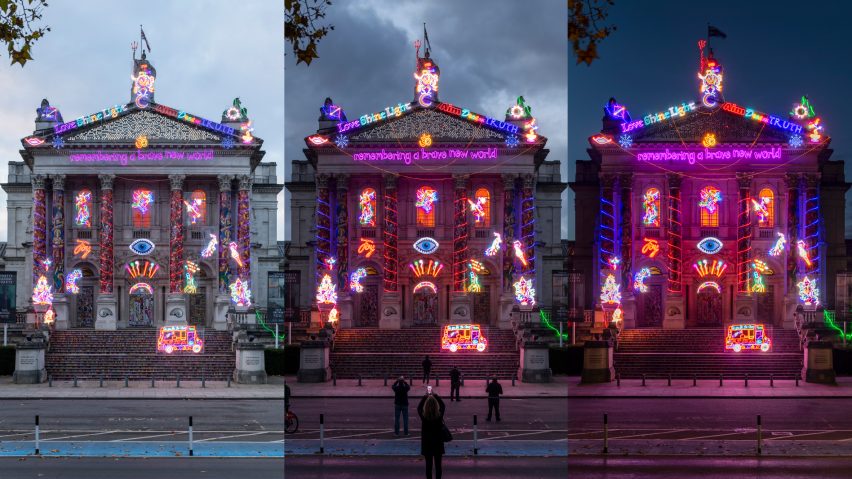

Bollywood posters and fluorescent effigies of Hindu deities have been superimposed on Tate Britain's portico, as part of an installation designed by artist Chila Kumari Singh Burman for the museum's fourth annual winter commission.

Entitled Remembering A Brave New World, the design was unveiled to coincide with Diwali, the five-day Indian festival which celebrates the triumph of light over darkness.

In this spirit, Burman clad the museum's facade in a menagerie of multi-coloured neon lights, which penetrate the darkness of London's shortening days, overshadowing the building's traditional, neoclassical architecture and its historical connotations.

"It's important to critique buildings like this because they're very Eurocentric," Burman told Dezeen.

"So, I just thought: why not do something that captures what we're all going through right now? I felt like it needed a blast of joy and light. And Diwali is about good over evil, about hope, unity and the light at the end of the tunnel."

Burman, who describes herself as a Punjabi Liverpudlian, drew on a bricolage of cultural influences to create the installation, which merges Indian mythology with pop cultural references, inspirational slogans and cherished childhood memories.

The luminous silhouette of an ice cream van, for example, which stands on the landing of Tate Britain's grand staircase, is a nod to the fact that her father purchased one after moving to England and struggling to find work as a tailor.

Featured next to positive exclamations like joy, love, light and truth, is spiritual imagery such as the third eye, the Om symbol and various deities such as the elephant-headed god Ganesha.

In a characteristic fusion of Burman's feminism with her Indian heritage, the artist also included an image of Lakshmi Bai, the queen or rani who once ruled the princely state of Jhansi.

Today considered an icon of freedom, she died on the battlefield while fighting off the British in the Indian Rebellion of 1857, surrounded by an army she had trained herself.

Perched atop the building's pediment, the iconic statue of Britannia is overlaid with an image of Kali, the Hindu goddess of destruction but also a saviour and protector who has come to be viewed as a feminist icon.

Emblazoned above, in playful subversion, are the words "I'm a mess".

"Most of us, because we're working from home, are waking up feeling a bit of a mess," said Burman. "So Britannia is a mess because I'm a mess. And everybody says: that's really good Chila because, in a way, Britain is in a mess."

To create a technicolour spectacle even during the daytime, the Corinthian columns are wrapped in fairy lights and larger-than-life versions of Burman's artworks, including the collage Punjabi Rockers, while doors are pasted over with posters of Bollywood stars.

"Originally it was going to be all girls but we didn't have enough images of girls that were high resolution, so I thought we'll add some men in it," the artist explained.

"I didn't want men on it, I don't know why. Some of the men look like idiots."

The installation will be on display until the end of January, with London mayor Sadiq Khan saying he hopes it will cheer up the capital's residents during the coronavirus lockdown and beyond.

"Chila's colourful tribute to her Punjabi and English heritage is a great way to mark Diwali's celebration of light over darkness and will be a symbol of hope during these difficult times," he said.

Tate Britain's previous winter commissions have seen Anne Hardy transform the building's facade into a ghostly ruin while Monster Chetwynd propped a giant, glowing slug on its balustrade.

The Tate came under fire this summer for a failure to tackle institutional racism in its galleries, with a mural depicting child slavery and Chinese caricatures on display in its Rex Whistler restaurant and an image circulating on the internet of its longtime patron, art dealer Anthony d'Offay, posing with a racist golliwog doll.

Under mounting public pressure, the museum has since cut its ties with d'Offay.

All images were taken for Tate by Joe Humphrys.