"The great challenges we face do not conform to neat disciplinary silos"

The coronavirus pandemic has revealed both a need and a desire for architects to adopt new ways of working, say the authors of Architects After Architecture, Harriet Harriss, Rory Hyde and Roberta Marcaccio.

The intersecting crises of 2020 – global pandemic, economic downturn, reckoning with racial injustice, all set against the backdrop of a climate breakdown – seem to be fundamentally incompatible with the profession as it is currently constructed. In many cases, the profession itself is part of the problem. While we all set out to do good, today we can instead find ourselves asking: "are we the baddies?"

Last year invited a radical reevaluation of priorities and revealed a latent desire for new ways of working. Architects and students of architecture are eager for new paths forward, looking beyond the arbitrary limits of the profession to address these systemic crises.

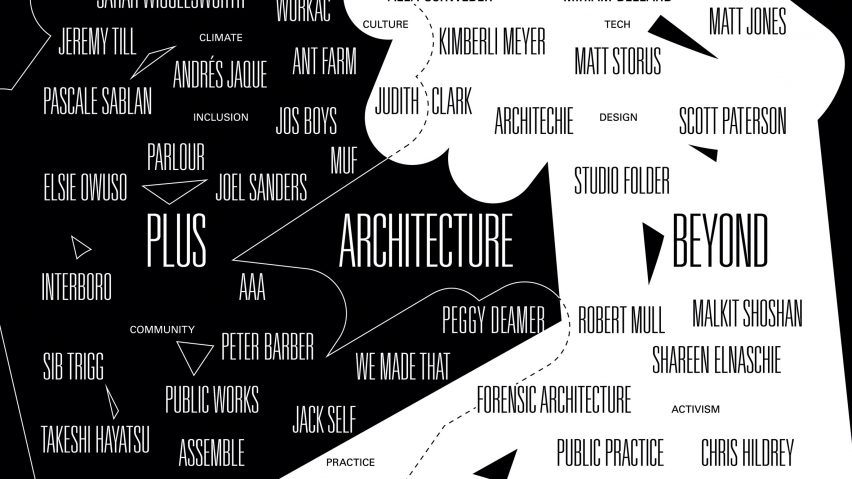

Our new book, Architects After Architecture: Alternate Pathways for Practice, brings together 40 practitioners who are doing just that. They have used their architectural training in new and resourceful ways, going beyond the conventional notion of practice, where one works on buildings commissioned by those who can afford it, to redefine who they work for, where they work, what kinds of questions they ask, and what kinds of answers they can give.

Last year invited a radical reevaluation of priorities and revealed a latent desire for new ways of working

We have assembled them into two rough groups. The first, gathered under the heading of "plus", are those who consider themselves to be still working within architecture, but who are stretching the boundaries, redefining what is possible.

We meet Interboro Partners, who have designed an adventure playground in collaboration with local children; Andrés Jaque, whose work reveals connections between architecture and sexuality, identity, and more; Pascale Sablan, whose Say It Loud exhibitions champion women and diverse designers; Holly Lewis of We Made That, who have forged a practice focused on strategy and research directed to the public sector, and many more.

The second group, under the heading of "beyond", is made up of those who have "left" architecture to apply their skills in other disciplines. They have recognised the broad applicability of the architect – as an integrator, a professional generalist, a practical idealist – and applied these skills in service of other questions beyond the building.

Together, they describe a future of architecture that is diverse and engaged, expanding the limits of the discipline, and offering new paths forward in times of crisis

We meet Miriam Bellard, art director at Rockstar North, creators of blockbuster videogames Grand Theft Auto and Read Dead Redemption; Matt Jones, principal designer at Google AI, developing technologies increasingly embedded in everyday life; Malkit Shoshan, whose ongoing work with the United Nations seeks to rethink the overlooked architecture of peacekeeping missions; educator Robert Mull, whose Global Free Unit places architecture students in refugee camps and other zones of uncertainty, and many more.

Together, they describe a future of architecture that is diverse and engaged, expanding the limits of the discipline, and offering new paths forward in times of crisis.

The number of architects who either leave or redefine what they do is surprisingly high. RIBA education statistics show that more than half of the students who have completed the undergraduate bachelor of architecture degree, known as Part I, do not go on to complete the post-graduate Part 3, a requirement for registration as an architect, representing a gap of around 1,600 students per year.

The great challenges we face do not conform to neat disciplinary silos

Rather than sweeping this cohort under the carpet, pretending that they don't exist, and letting them find their own way, what if we were instead to acknowledge their diverse roles and pathways as signs of success? The broad applicability of architectural thinking beyond the building is surely a strength rather than a weakness, it suggests a flexibility of mind, and a high level of transferable competence. Further, what if architecture were promoted as a generalist degree, a way of thinking about the world, rather than a step toward professional accreditation?

It is this flexibility of mind that society needs most of all today. The great challenges we face do not conform to neat disciplinary silos, but cross over into the messy space between politics, economics, culture, and – critically for architects – spatial thinking.

These challenges are defined by their interconnectedness and by change. They cannot be solved with the old processes, but require new forms of thinking and working, combining a planetary consciousness with a responsible humanism that respects and enables local expertise. We find this to be hugely encouraging, a reminder that the architect's combination of skills is what is needed now, if only we can be brave enough to free these skills from the constraints of the building.

But why should architects apply their skills elsewhere? "Stay in your lane!" you cry. "Focus on designing buildings, on what you're good at!" A fair point perhaps, but it overlooks the state architecture finds itself in today. A 2018 headline in the Architects' Journal stated that "Brickies earn more than architects".

There is no reason why a brickie shouldn't be paid more – it's a hard job, and you should be rewarded for doing it – but given the time and expense it takes to train as an architect, this should be a harsh wake up call for all of us. In this book we argue that it is only by going beyond the building, and reframing our work around the public good, that we can recover the unrealised value of architecture today.

A number of the contributions take the form of the personal narrative, the journey from architecture education to their ultimate destination. Most people and practices forged their paths in times of crisis. Faced with great challenges, as we are today, they were forced to reevaluate their priorities and reinvent the way they work.

It is our hope that through these individual stories, of pursuing passion and opportunity, the reader may recognise their own ambitions, and discover a path which they may learn from. But more importantly, through the accumulation of these stories, we hope to illustrate a version of architecture where the limits are no longer fixed, but able to be designed and redesigned. It is by charting these many alternate pathways that we can discover the unrealised potential of architects after architecture.