As well as being bad for the environment, NFTs have so far failed to produce original or exciting work that pushes the boundaries of design, says Aaron Betsky.

When will we see good design as a NFT? That is, for me at least, the real question that arises out of the very sudden and meteoric rise of the value and the spread across the design world of what are essentially novel funding devices that are used by artists and designers, as well as collectors outside of the field.

Just as a refresher: a "non-fungible token" is a bit of blockchain-encrypted code that you can own and use in whatever manner you like. That ownership guarantees authenticity, but not uniqueness, as the maker could easily create another version of the same, in the manner artists sometimes redo the same image more than once – think Munch's The Scream or De Chirico going back and recreating his most famous paintings decades later.

NFTs have an ethereal and evocative quality that belies what might happen if you tried to construct them

The token is not an instructional manual or blueprint and is in fact not meant to lead in all cases to something that is realized in meat-space. Its beauty and its worth, lie in the freedom it thus has to be expressive and most of the works sold as NFTs have an ethereal and evocative quality that belies what might happen if you tried to construct them.

As such, NFTs could function in the manner of "paper architecture": they could offer visions of what could be without worrying about how that utopia could be realized. There is a long history of such images in architecture and design, starting with Ledoux's and Boullée's attempts to turn the excitement of science into unbuildable structures such as Newton's tomb, a giant sphere that even today would challenge any attempt to construct it.

A long line of designers has dreamed of floating cities, gravity-defying objects, and total environments that would cushion and support us with not much more than air. The advent of linked computer and communications technology in the 1990s boosted makers' ability to propose what they could not make in forms that were seductive and even convincing.

What we have gotten so far are amateur, off-hand sketches that have no sense of pushing our notion of what a designed object is

When I first heard about NFTs, I hoped that the likes of Markus Pasig or Perry Kulper, or even experimentally minded real-world makers such as Yves Behar or Karim Rashid, would use it to support their activities, which until now they have only been able to do through teaching or producing more objects, while also proposing forms and images that would inspire us all.

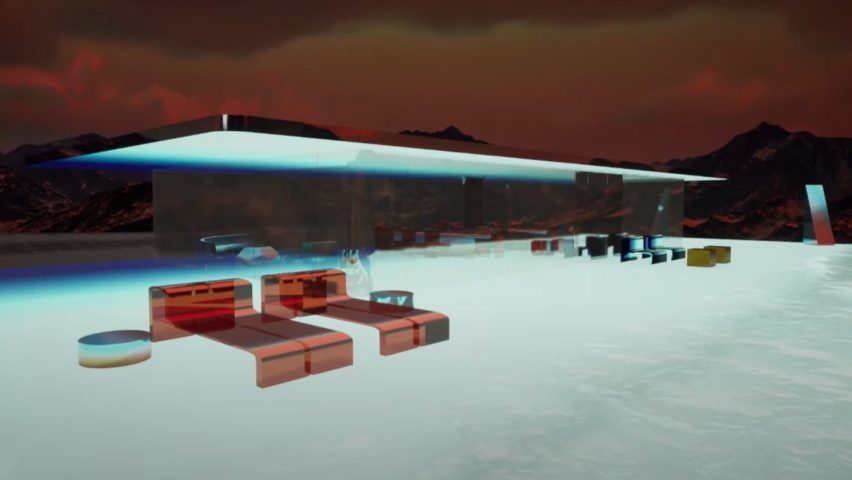

Instead, what we have gotten so far are amateur, off-hand sketches that have no sense of pushing our notion of what a designed object, image, or space is beyond what you can find in the showrooms or showcase houses. Whether it is the dreamy house that sold for $500,000 or the pieces of furniture that float on rocky coasts or deserts waiting for Lawrence of Arabia to appear in the corner of the frame, the NFTs I have seen all confirm notions of design that have in fact been made in real life – 10, 20, or even 30 years ago.

Not only that, but they are bad versions of these designs, with proportions that lack any grace, unresolved curves and protuberances, and other flaws that would bring out the editing pencil in any good studio.

The NFTs I have seen all confirm notions of design that have in fact been made in real life – 10, 20, or even 30 years ago

The counterargument might be that such standards are so last millennium. To judge work created in this new medium and for a whole new audience that is obviously willing to pay for these efforts according to standards developed in architecture, art, interior design, or industrial design is obviously to miss the potential of these forms to appeal beyond elite and hidebound standards. These objects are already good according to their own logic and that of the market that pays for them.

I would beg to differ. There is actually good work going on in digital-native art and design, which is the general category to which NFTs belong from an art-historical perspective. It has been appearing for a few decades, actually, and has produced work that is both beautiful according to established aesthetic and functional standards, and that pushes those notions beyond what we know.

In addition to some of the experimental architects I mentioned above, there are artists who have been working in the realm of digital-native work, ranging from the Belgian collective Jodi to the New York artist Wade Guyton (although he translates his work into physical artifacts), for quite some time. There now is also quite a body of theoretical work, such as the notion of "post-orthographics" developed by Harvard Professor John May, that helps us understand what could be possible in this realm.

Sure, they are popular, but then so are romance novels and paintings of dogs playing cards

To reject such categories of criticism means going a step further, namely to reject the whole notion of standards, judgement, and the implied possibility that a truly good work of art or design, however defined, has the power to act as a critical catalyst, to amaze or frighten us, and to be deeply satisfying in a way that stuff run off with no sense of discipline or skill does not.

You can do that, of course, and obviously you can make money doing so. Perhaps the real role of the NFT will be in the production of images that extend the digital renderings developers produce of their luxury condos before they are built, or that show the bathtub sitting out in the wilds where there is no plumbing.

The problem is that it is difficult to argue for such images as works of art that we should concentrate on and pay for at the prices some of them now command. Sure, they are popular, but then so are romance novels, paintings of dogs playing cards, and the designers that clutter our homes, offices, and places of play with useless and ugly crap.

This does not mean that NFTs do not have a bright future – or development in the nebulous space/time continuum in which such digital-native work exists – but that the first pieces that have hit our collective consumption stage are not worth the code they are written in. And, by the way, current modes of bitcoin mining and thus producing NFTs are so staggeringly wasteful of natural resources that to engage in making such objects is, for now, an environmental crime on top of all of this.

The main image is of Mars House by Krista Kim, which last month became the first digital home to be sold as an NFT.