As campaign group FAF calls on RIBA to address the mistreatment of architectural assistants, architects should focus on changing toxic practice culture, says Sylvia Aehle.

I have been tempted to glorify the idea of the architect as a tragic hero, perhaps because I loftily draw parallels between the juxtaposing (and sometimes tragic) traits within me and those of the architect I want to be.

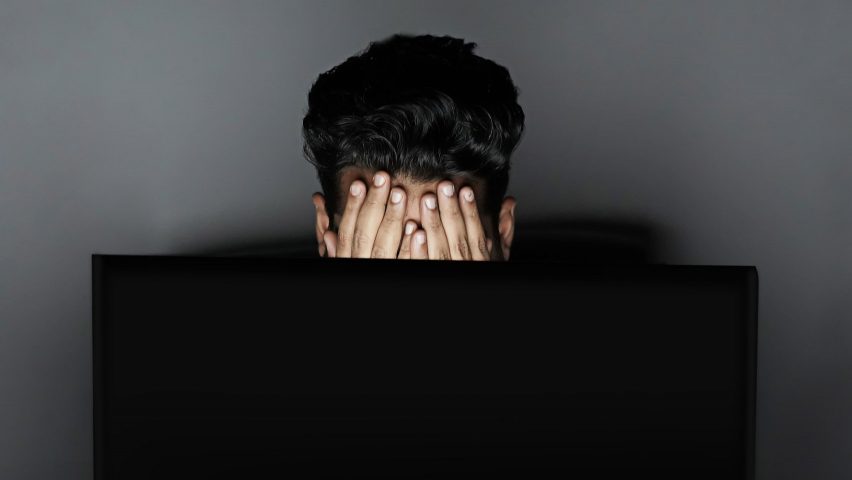

Like me, the architect – especially during those endless, endless, endless years of education – is a recluse, draped in black, working autonomously into the early hours, disappearing into a black hole of self-pity. And despite the self-contained world we make for ourselves, we are also a force that presents fantastical, proud ideas, ideas designed to reimagine and uplift society.

Is the system we are part of equipped to support aspiring architects to make meaningful architecture?

Once indoctrinated into our discipline when we are outside the walls of the studio, the latter part of the diligent student's process is too often buried. We become painstakingly aware of the years it takes to have an impact and make a living worthy of all the hours we put in. But how many architects reach a place of influence where they can make change or create structures that speak to our culture?

A better question might be: Is the system we are part of equipped to support aspiring architects to make meaningful architecture? In the eyes of the recently formed campaign group, Future Architects Front (FAF), perhaps not. In its recent open letter to the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), it called on the institution to address the poor way that many architectural assistants are treated in practice.

The open letter was supported by 1,800 signatures from architectural assistants, designers, and architects, and describes how some assistants are on zero-hour contracts and are pressured into working hours of unpaid overtime and how some have even been offered a pitiful salary of £16,000 per annum.

The irony is that none of the shocking accounts of mistreatment is news

The letter urges RIBA to step in and regulate the employment of assistants – it also included over 150 anonymous comments from assistants who took part in the survey; one assistant recalls: "I believe I spent the entirety of the year both physically and mentally burnt out."

The irony is that none of the shocking accounts of mistreatment is news; not to RIBA or to those within the profession; everyone is aware of what practice cultures can be like. Working within "fast-paced" – code for toxic and high pressured – environments, with unpaid overtime and long hours is often a given. It shouldn't be like that.

FAF has amassed a large following on Instagram with over 3,000 followers and a continued outpouring of support across social media. The RIBA has also responded to it, promising to work with FAF and state that they "feel confident that [they] can find solutions to improve the opportunities and experience for students and graduates." We eagerly await these changes…

Architectural practice as we know it is going through major changes. In 2019, the RIBA published a response to the Home Office's statement confirming that architects will be added to the Shortage Occupation List. Alan Vallance, chief executive of the RIBA, said: "Currently 25 per cent of UK-registered architects are international… since the referendum there has been a drop-off in registrations from EU architects, and we are concerned about the impact of this on recruitment."

Surely the abundance of architects is the reason for the mismanagement of many of my peers

There are two factors to consider; firstly, what are the implications for architecture in post-Brexit UK? Do we solemnly watch on as our European counterparts disappear down the Channel Tunnel? Secondly, as a Londoner emerging into the profession, the claim that there is a shortage of architects in the UK seems like fake news!

Surely the abundance of architects is the reason for the mismanagement of many of my peers – it appeared that the market was oversaturated with architectural staff at all levels and that this was partially to blame for the outdated and sub-par working conditions to which trainees have been typically subjected.

We know the hours, blood, sweat and tears it takes to see a glimpse of success, yet we willingly go through the drawn-out process of education followed by unfulfilling roles. I believe this again stems from the idea of the tragic hero, in an echo of the terminology used by Aristotle, our hamartia has led us to believe that in order to succeed we have to suffer and that this suffering is for the greater good.

But it's okay to put down the metaphorical cape, it's okay not to save the world! The sooner we strip ourselves of this hero complex – myself included – the sooner we can get more out of the profession.

There is a gradual shift happening

Maybe it's time we reimagined the other ways we can be agents of society, what can we learn from the developers, contractors and project managers that we love to hate? Years of education and a large amount of debt compels us to expect miracles from a profession that needs a reboot.

Thankfully, there is a gradual shift happening, the demand for architects and groups such as FAF emerging is good news, we are at an advantage. Although shedding the toxic behaviour we have grown accustomed to will be met with resistance, mainly by those who simply refuse to take off their cape and are bound to the idea that suffering for our work somehow equals excellence and integrity – they wish we would stop whining and get back to our Revit models, and that simply is not an option.

There are a lot of outdated ideologies to overcome, but the desire and actions towards change certainly sets the tone for a new type of architect and practice that will hopefully continue to create work that is valued correctly and engages with society.

In this world we have made for ourselves – in our age of instant gratification, exemplified by Uber, Instagram and Deliveroo – perhaps we can fast forward to the good part too.