Central Saint Martins graduates Brigitte Kock and Irene Roca Moracia have collaborated to create concrete-like tiles that give new "economic and ecological" value to invasive species.

The material for the tiles, which the researchers refer to as bio-concrete, is made from Japanese knotweed and shells from American signal crayfish.

These are among the non-native species that are causing the most ecological and economic damage in the UK. By adding value to them, Kock and Moracia hope to incentivise their removal and help restore local biodiversity.

"Invasive species removal and control costs the UK around £1.8 billion annually," Moracia told Dezeen.

"The harvested material is incinerated, buried or trashed. We want to stop this waste. We do not want to create a new industry around this product but to relocate the waste the current system is producing."

The project was commissioned as part of the Maison/0 graduate programme by the LVMH group, which counts Dior and Louis Vuitton among its brands, with the aim of developing a sustainable alternative to current building materials that could be used in luxury store interiors.

Kock and Moracia decided to target concrete, a major carbon emissions culprit. Rather than just mitigating its negative environmental impact, they set out to create a substitute that is actively beneficial.

"We live in a moment when there is no time to question if something should be sustainable; I think our generation understands the need for a sustainable future," said Moracia.

"However we think this is not enough if we really want to make a change. So we wanted to create a positive impact — a regenerative material."

The researchers looked at finding a new purpose for invasive species, which are among the top five threats to biodiversity worldwide, and chose to use Japanese knotweed and the American signal crayfish.

Japanese knotweed was introduced to the UK in the 1800s and has no natural enemies in the country. When left unchecked, it can grow through concrete, compromising the structural integrity of buildings and roads, and overwhelm other plants to damage ecosystems.

Similarly, since they started being imported to the UK in the 1970s, American signal crayfish have decimated the native crayfish population.

Their tendency to burrow into river and canal banks has changed local water quality, and can lead to floods and infrastructure collapses.

Kock and Moracia were able to source both species from specialist removal companies, before combining them using a recipe based on the volcanic ash concrete developed by the ancient Romans.

"We have followed their principles and created a bio concrete with different recipe variations," Moracia said.

The knotweed, which is incinerated after removal, acts as the ash binder, while pulverised crayfish shells are used as the aggregate instead of the traditional rocks or sand, as these can contain fossilised carbon.

Combined with water and gelatine, these ingredients create a strong, homogenous material that cures and hardens without the need for added heat or synthetic colouring.

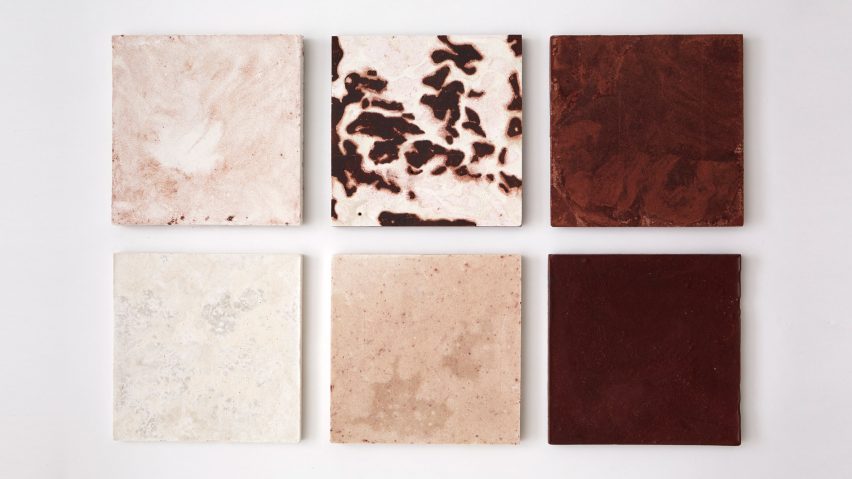

"We have played with the percentages and ratios to obtain really strong results," Moracia explained. "The final colours and textures depend on the curing time and the aggregate's chemical reactions with the binder and the water."

Through adjusting these variables, the material can take on a range of different finishes to replicate raw concrete or the delicate veining of stone or marble.

Its colours vary from a pale, minty green, created by firing the crayfish shell, to a deep burgundy colour that develops in the curing process when pieces of raw knotweed root are included alongside the ash.

At the moment, the project is still in its infancy and Moracia estimates it will take "years of work" to create a standardised product.

One crucial hurdle is that building regulations and rules around the disposal of invasive species would need to be changed to allow for commercial use.

Currently, invasive species are labelled as hazardous waste once they are removed, making it difficult to repurpose them as raw materials.

"We want to showcase the absurdity of the classification and disposal rules here in the UK that do not allow anything to be done with those species after they are treated and sealed in bags, while you can easily order those byproducts online and import them from China for example," said Moracia.

"Rather than having them labelled as hazardous waste, we wanted to integrate them into a production process so that they create economic as well as ecological gain."

Previously, Moracia worked on a similar project to create a series of modular furniture from unused building materials.

In a bid to substitute polluting building materials, a number of experimental, organic alternatives have been proposed in recent years, including Dead Sea salt bricks, a concrete substitute made from seashells and construction boards made from waste paper.